Cyberpunk 2077

Too much is too much

PC, Xbox, Playstation, Steam Deck

$24.99 to $29.99

24-60 hours long

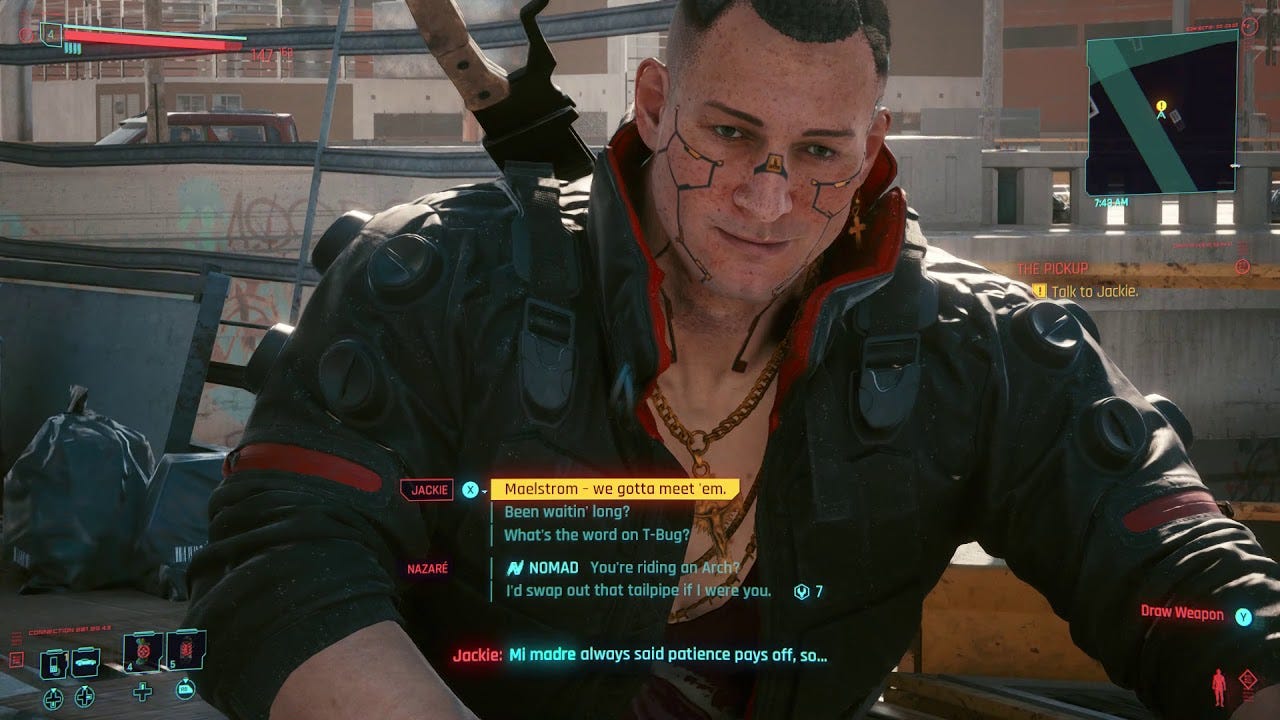

Cyberpunk 2077 is an action roleplaying game (RPG) set in the futuristic Night City. You are a mercenary named V, taking on quests involving talking, shooting, hacking, and driving. It combines cutting-edge graphics with an expansive open world filled with countless buildings, weapons, and vehicles, resulting in one of the most technically impressive games in recent years.

Like many RPGs, you can customise your character’s appearance, backstory, and attributes before you begin. This is a little confusing because many players won’t know what impact their choices will have (pretty minor, as it turns out), plus you rarely get to see your own character anyway as game is almost always presented from a first-person perspective.

I chose “Corpo” as my backstory. In the world of Cyberpunk 2077, which is based on an older tabletop RPG, megacorporations dominate a violent hypercapitalist dystopia where mercenaries, drugs, and prostitution are commonplace. My game began in a bathroom in the Arasaka Corporation, looking in the mirror (one of the few times the game makes you see yourself) and having a simultaneously confusing and boring conversation with someone my character knew but I didn’t.

It’s a brave choice to begin a game in medias res, especially when the player is assuming a character who isn’t an amnesiac or just woke up from a century-long cryogenic sleep, but instead has lived in Night City for many years and built a career, sidejob, friendships, and a deep knowledge of the world of 2077, literally none of which the player knows one bit of.

Good writing can make this work. Unfortunately, Cyberpunk 2077 does not have good writing. It totters between overexplanations (“you do realise who you’re talking to, right? I saved your ass in Mexico!”) and jargon-laden enigmas (“let’s klept militech’s flathead from those gangoons”). You eventually get the hang of it, but it’s a poor start that sets the stage for dozens of hours of overwritten dialogue.

Exiting the bathroom, I wandered through an enormous brutalist lobby to meet with my boss, who naturally wanted me to kill a rival. On the way, I passed some of the most detailed office pods I’ve ever seen in a game, which was deeply impressive until I realised they were all identical. I then sat in a hovercar that flew over vaguely Japanese neon-drenched towers ripped straight from Blade Runner to arrive at a nightclub. While sitting down with my literal partner in crime to discuss killing my boss’ rival, I got caught and yet more story unfolded.

Open world RPGs like Cyberpunk 2077 are meant to give players a lot of freedom. You might not be able to do anything you want, but you can usually choose what order to do things in and where to explore next. Lately, big budget games (AAA in the industry parlance) have added lengthy, highly-linear prologues before allowing players to go off on their own. This is understandable insofar as it’s thought necessary to establish the setting and rules of the world, but often the prologue goes on far too long. One might think this is like forcing a romantic comedy fan to sit through an hour of horror before seeing Julia Roberts do her thing – and one would be correct.

Of the fourteen hours I’ve played Cyberpunk 2077, six were devoted to the almost totally-linear prologue and the remainder was mostly spent on a handful of totally-linear main quests. These hours were indistinguishable from linear story-driven games like The Last of Us and Uncharted, in that I didn’t have any choices to make and I was mostly being driven between locations where I would alternately talk and shoot at people, albeit in very pretty surroundings.

Now, I like linear story-driven games. Purists deride them as being barely different from movies but as long as they’re entertaining movies, I don’t mind. And so, just like movies, the best games end up being highly edited, whether that’s in movie-like cutscenes or levels being designed in ways to not waste players’ time.

But Cyberpunk 2077 isn’t edited. At all. A typical quest will see you arrive at a meeting point, wait for a car to pull up, your contact to leave the car, walk over to you, have a chat about collecting a box; then you walk to the car, open the door, get inside, wait for the car to start, then have an unskippable dialogue sequence about the box you’re collecting while your contact drives you through the city for a few minutes. You arrive at your destination, get out, walk to the shack, open the door, pick up a box, walk back to the car, open the trunk, put the box in, then drive somewhere else.

Your tolerance for Cyberpunk 2077 as a whole relies on whether you think this sounds like a triumph of hyper-immersive storytelling enabled by the technical achievement of it all happening “in engine” (i.e. not a pre-recorded video), or an incredible bore that would be improved if it were ten times shorter. Early on, one character will complains, “why does it take two minutes to set this rig up?” and another replies with two minutes of pointless dialogue while you’re sitting on a chair unable to move. Writers: you are the people making it two minutes long! You could just make it 30 seconds long! I had to laugh when an option to say, “Sorry… but is this gonna take much longer?” appeared during an especially interminable debate.

When we talk (or complain) about cinematic storytelling in games, we aren’t only referring to players listening to characters without making any decisions; the “cinema” part means you need editing. I cannot for the life of me understand why some people are so impressed with “single-take” game storytelling, where the entire experience has no cuts at all. It’s mixing up technical achievement with good storytelling.

Even the most propulsive heists and set pieces are badly edited, with stilted dialogue so poorly timed I thought the game was incapable of playing characters’ lines with less than a second’s gap between each. The odd thing is that when the game does allow you to skip dialogue, it’s accompanied by a very nice, deliberately glitchy, visual effect. The game’s rare hard cuts have similar cyberpunk-ish visual innovations, but they’re all too few. Also odd: the central plot of Cyberpunk 2077, involving your brain getting taken over by someone else, is somewhat intriguing from a sci-fi perspective and provides a good reason for you to get into lots of trouble. The problem is that it takes six hours to start. So maybe just cut those first six hours?

For all its ambitions to be an immersive RPG, this game really just wants to be a story-heavy linear action adventure like Uncharted and God of War, except it’s really bad at that. This would be forgivable if the gameplay and world were especially good and unique. Spoiler: they aren’t.

True immersive sim games provide multiple ways to complete every quest, usually including non-combat solutions such as diplomacy. Cyberpunk 2077 feels like it should be an immersive sim because you can walk or drive almost anywhere and there are so many abilities and weapons and character stats to improve; but to be fair, it’s never claimed to be one. So in the absence of diplomacy, the combat better be good.

It is merely fine, which for this kind of game really isn’t good enough. It adopts a common RPG style of combat where enemies have health bars that you chip away with attacks; when you last a bullet or apply a quickhack (basically, techno-magic spells), numbers fly out of the bar. For me, this is the opposite of immersive and is designed for people who like min-maxing their weapons loadouts, and the resulting drawn-out fights are one reason why I stopped playing recent Assassin’s Creed games. That’s my personal preference, however, and I thought Fallout, which has a similar system, is just fine because I like other things about it. But Cyberpunk 2077 doesn’t do anything new with the formula; in fact, its deluge of weapons and upgrades and add-ons make it worse. I just don’t think it’s fun to sort through ten near-identical rifles in your inventory to figure out which one is best.

The reason you have ten rifles and a hundred other things (food, drink, clothes, upgrades, junk, data “shards”, health kits, etc.) is because everyone you kill drops them and every location has stuff lying around. It took me a little while to realise items were colour-coded for rarity, which is linked to quality – but only approximately, since health items don’t stand out but are always useful. This means much of your time is spent collecting things and deciding which to keep or sell. Again, this is a common RPG malady, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be improved upon – The Last of Us 2 has a nice accessibility setting that lets you detect and automatically collect items without pressing a single button.

The same embarrassment of riches extends to your character’s stats, which govern everything from your combat and hacking prowess to your reaction times and how much you can carry. There must be a dozen of these ability screens, each with 15-25 abilities, many of which can be levelled-up more than once. Experienced RPG players may have some idea of which abilities map on to their playing styles, but I had no idea what to focus on. How to weigh up an extra 3% damage from rifles vs. a shorter cooldown on quickhacks? The game’s perfunctory tutorials, buried in endless jargon-filled dialogue, did little to help.

Cyberpunk 2077 is one of those games where you’ll pull over a friend and say, “look at these graphics!” and they’ll nod and say it looks very good, then wander off. This is partly because it’s one of the first big games to introduce ray tracing, enabling especially realistic lighting and reflections. Ray tracing works very nicely in a cyberpunk setting with all the neon lighting and shiny floors and grimy alleyways with puddles. It’s an undeniable technical feat, but I can’t bring myself to care all that much. Video game graphics have looked great to me for years and while I can recognise the improvements, they don’t offer the same leaps in immersion or enable new gameplay in the way that 3D or HD graphics did.

More important is what the graphics are depicting, which is nothing I haven’t already seen a million times in Blade Runner or other derivative cyberpunk environments in Star Wars or similar. Cyberpunk is old hat now! What might have seemed edgy and fresh even a decade ago has been done over and over again in every media conceivable, and certainly in video games.

Worse, the cyberpunk aesthetic suffers from being spread too thin. Night City is a big city when it comes to video games, and endless moody dark alleyways and retro-futuristic container shacks and sleek skyscrapers offer too little variety. In aiming for perfect verisimilitude in the details – the food carts and vending machiens and nightclubs do look very realistic, even if they’re mostly cut and paste jobs – they’ve missed the greater goal of creating an interesting world. Less is more, and more is less.

Despite the city’s size, driving is slow and claustrophobic. Streets are narrow and it’s hard to weave through the traffic, especially with so many right-angled turns. This is arguably “realistic” in the sense that driving through Manhattan or Bangkok or London is equally miserable, but that doesn’t mean you should put it in your game, let alone spend countless thousands of hours designing highly detailed cars, all with their own custom instrument clusters.

The entire notion of private transport is odd in such a dense city. Maybe I’m being pedantic but if the game wants to be realistic, why not add hovercars or turn its fast travel feature into a more fully-realised public transport system, where you could meet people and have conversations? There’s little point in putting driving into a game if it isn’t going to be fun, except to check a box on a list of “open world game” features.

The closer it gets to reality, the more wrong Cyberpunk 2077’s world seems. There are countless shops and buildings that look “real” but so few you can enter; vast plazas and apartment complexes with barely a crowd; a whole world to explore but so little to do.

Even the most ardent Cyberpunk 2077 fans will admit the main story is mediocre. “Just do the sidequests!” they’ll say. The first proper sidequest I played was good, where I consoled a recluse about a loss. It was probably the best moment in the entire game: the best writing, the best acting, and no shooting whatsoever.

I couldn’t wait for more. I began accepting all the texts and calls and shouts from random passersby asking for help until I realised they were all identikit sidequests like hunting down cars and spotting graffiti and dealing with minor hoodlums. I’m sure some people like these things but I found them a distraction. In fact, after 14 hours of play, I’d barely seen any unique sidequests. Apparently they appear dozens of hours into the future.

By this point, I’d finally found my footing. I figured out how quickhacks worked; I understood the point of cyberware and RAM upgrades; I focused on boosting my stats for my style of play. The game’s compulsion loop had kicked in, too: accept quests, get cash, buy new quickhacks (magic spells) and cyberware upgrades (magic capacity), take on harder quests, etc. It was the same addictive feeling I’ve gotten from RPGs like Fallout and Dragon Age, games I’ve sunk dozens of hours into. I stopped caring about Cyberpunk 2077’s bad story, I only wanted just one more level-up, one more upgrade, one more quest.

But what would be the point other than to pass the time in a comforting world whose rules I’d finally learned, accumulating a bunch of meaningless items to make some numbers go up? Cyberpunk 2077 has mastered the classic RPG compulsion loop but it has nothing else to offer except an overlong, badly written, badly-edited TV show of a story with the occasional standout one-off ep.

That wasn’t enough for me, so I stopped playing.

The not-so-secret thesis of this newsletter is that incredible, exuberant variety of video games has a flip side, which is that it’s all too easy for games to hamstring themselves by indulging niche audiences, making themselves impenetrable to all but the most faithful. Fans wave away criticisms of the ultra-linear six hour prologue by pointing at the precious sidequests, but a well-designed game wouldn’t take players for granted like this one does.

Cyberpunk 2077 cost over $300 million, took the best part of a decade to make, and its staff endured months of long hours and six-day weeks. It’s inexcusable that so much time and money would be spent on something that’s no better than any other RPG, and arguably much worse and far less accessible. It doesn’t do anything brave, and other than nice graphics, it doesn’t do anything new.

It’s a waste of time.

Exactly my experience too. Although for some reason, Ghostwire, which suffers from much of the same afflictions, and is a much smaller budget game, is fun for me in an inexplicable way.