Eye of the Temple

A clever experiment in VR movement doesn't make up for a lack of fun

Meta Quest 2, Steam VR (requires 2x2m play area)

$19.99

2-4 hours

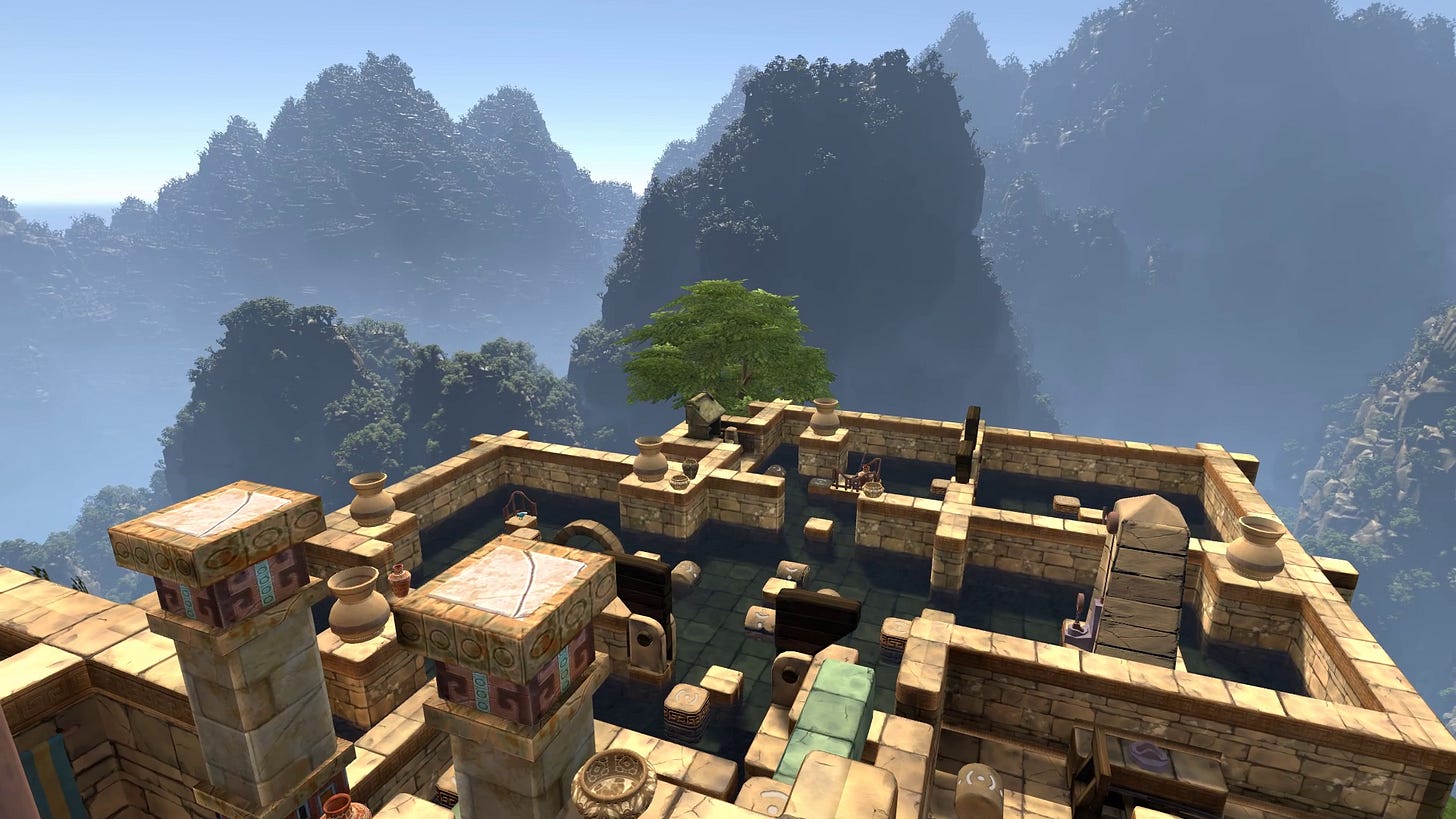

Eye of the Temple is a VR adventure game where you explore a sprawling temple filled with treasures, traps, and puzzles. You’ll pull levers to move bridges, light fires to unlock doors, smash pots to collect gems, and fight flying scarabs with your whip and flaming torch.

All movement is via floating platforms and walking atop rolling barrels whose routes are cleverly designed such that any combination will always keep you within the same real world 2x2m square. In other words, if you step to the left (within your room) to walk onto a moving platform, you’ll soon end up stepping to the right; or if you’re on a walking backwards on a rolling barrel, you’ll soon have to step forward.

This system of movement scales across the game’s vast network of towers, dungeons, ravines, and courtyards so that you never have to break the illusion you’re “really” there, unlike other kinds of VR movement like teleportation, where you point at a place on the floor to move there instantly. Unfortunately, the limitations of this innovation, along with Eye of the Temple’s unwillingness to broaden its appeal via interesting puzzles or varied environments or any kind of story or characters whatsoever make it extremely limited as a game, and ultimately, not very fun.

Now, I’m going to be very critical of Eye of the Temple. You might wonder why I’m bothering to write about it at all, given it’s a small-budget game made by just one person. The answer is that it attempts a new mode of locomotion in the still-nascent medium of VR, which I believe will one day become the main way we play video games. It’s also a good opportunity to explore some pretty basic points about what makes for good and bad game design.

I’ll set aside the fact that most VR games avoid putting players on moving platforms due to the motion sickness-inducing mismatch of what you’re seeing (movement) and what your body’s vestibular system is sensing (no movement) for now; the game acknowledges this and claims, mostly accurately in my case, that you’ll soon get used to it. The real issue is that you spend way too much time waiting for platforms to arrive as they slowly float back and forth between their destinations. In most games, this waiting time would be filled by a companion or someone on a radio providing backstory or banter, but in two hours of playing Eye of the Temple, I saw no pretensions to any kind of story or even world-building beyond your standard Indiana Jones-like fedora and whip and the generic central-American-styled temples.

When you do make it onto a platform, you’re often presented with trails of gems to collect by waving your whip or your torch through them. What are the gems for? I couldn’t tell you, but I can say they’re distracting enough to get you off-balance, which is inconvenient when you’re trying to crouch to avoid a stone block descending from the ceiling.

I used the whip for two other things: lassoing levers to pull them (a neat idea, even if the physics are shaky) and fighting scarabs. The fighting required some serious flailing; after I died twice in a row, the game informed me I wasn’t hitting hard enough. A warning to aspiring VR designers: this is not a good idea for a game meant to be played in smaller rooms. Luckily, it’s stocked with plenty of checkpoints to restore from in case you die or fall off a platform, which happened literally every time I paused to remove my headset.

As for the lever-pulling, this was in the service of simple puzzles that never threatened to occupy my attention for more than a minute or two; the most interesting one I saw involved rotating a bridge so the lever at one end became lasso-able from another ledge.

The wayfinding in Eye of the Temple is surprisingly confusing for a game all about immersive exploration. I’d frequently enter a new area and pick an enticing route only to discover it was a dead end, accessible only after I’d progressed elsewhere. This was partly the fault of the low-ish resolution of my Meta Quest 2 headset, but mostly due to confusing art design. If the game had teleportation or I were playing on a console and could sprint everywhere, this wouldn’t be as noticeable, but the slow moving platforms and their associated motion sickness meant any wasted travel was especially annoying.

You’re never clearly told once you’ve “completed” an area, either. I don’t know whether that’s thanks to the game’s consistent pursuit of immersion above all or merely an omission, but I wasted a bunch of time looking for more levers to pull and fires to light before discovering there weren’t any. This is where a companion would be helpful, or even a plain old “Area Completed” message. Simple stuff, but important.

Room-scale VR games like Eye of the Temple are more tiring than console and smartphone and PC games, if only because you’re on your feet rather than sitting down. But Eye of the Temple introduced a new problem: a crick in my neck from looking down all the time. There are a lot of games where you have to step very carefully, like Dance Dance Revolution or Beat Saber, but the precision demanded by Eye of the Temple is something else, especially when a single false move on a moving platform means instant death (immersion strikes again!).

Being uncomfortable isn’t a dealbreaker. There’s nothing comfortable about playing the violin, but people tolerate it because there’s no other way to produce that kind of sound. But as we’ll discuss later, there are alternative modes of VR locomotion, and they’re definitely more comfortable.

Eye of the Temple makes welcome concessions to accessibility and comfort in other ways, however. You can make it so you have to crouch less under descending blocks, and you can reduce motion sickness by adding blinders to block your peripheral vision while riding in minecarts (so it feels more like you’re watching TV rather than sitting in a moving vehicle).

But none of that makes the game any more fun. In one dungeon, I had to walk across a series of rolling barrels while a ceiling descended to crush me. This wasn’t especially hard but it required perfect timing, right down to the second. That’s a hard ask when players might be tempted to dive or jump the last few metres toward safety and in doing so ram their face into a real-world wall. I didn’t do that, but getting crushed on my first couple of tries was extremely unpleasant.

On escaping the dungeon, I found myself atop of a steep gorge with a series of puzzles below. As I made my way down, I had to take a detour into some caves with yet another crushing ceiling. It was then that I knew my time with this game was up.

Eye of the Temple’s moving platforms and rolling barrels are a new attempt to enable space-squeezed VR gamers to walk around large virtual worlds using their real-world legs. It follows on from earlier attempts like environmental redirection, featured in Triangular Pixel’s Unseen Diplomacy from 2016, where large-seeming rooms and levels are designed to limit players movement within small physical spaces, arranged in a reality-breaking way so that they sometimes lie on top of each other (elevators are good at solving this problem). Unseen Diplomacy requires 3x4m, which I managed in my old office but can’t in my home; the newer Tea For God needs less space but works in the same way, albeit with much narrower corridors.

Environmental redirection is different from another, even cooler method you might have heard of: redirected walking. This manipulates the virtual environment around the player so that if you turn 5 degrees clockwise in the real world, you might turn 7 degrees in virtual reality. Taking this to the extreme, redirected walking can make you think you’re walking in a straight line in VR but in reality you’re going in a circle. This has limits – your vestibular system can only be fooled so much – and it only works with a pretty big room, which most people don’t have.

Most of the VR games I’ve played don’t use either technique. Often this is because, like Beat Saber, they involve very little walking and much more shooting or dodging or hitting. When VR games are about exploration, like the Star Wars titles, they typically use free movement or teleportation.

Free movement is where you push an analog stick and the world moves past you, like in console games. It notoriously induces motion sickness in VR and I prefer not to use it. Teleportation, on the other hand, produces next to no motion sickness for most people. It’s theoretically much less immersive in the sense that you can’t actually teleport in real life; the Eye of the Temple developer argues “once learned, [teleportation] still takes focus away from experience and reduces immersion.” This is true insofar that all indirect control mechanisms, like a game controller’s analog stick, are less immersive than walking in real life; the question is whether the benefits of teleportation or analog sticks are worth the reduction in immersion. For teleportation, one benefit is that it’s far faster than moving platforms.

Some people advocate for using mixed reality or augmented reality (a distinction without a difference, IMO) to turn your home itself into a game: zombies hiding behind your bedroom doors, wormholes appearing in your kitchen fridge, that sort of thing. Like almost all augmented reality ideas, this looks great in a demo video but is extremely limiting when it comes to game design – I can’t see a good way to remap an ancient temple onto my house’s weird layout, let alone everyone else’s. The best thing about VR is how it can transport you to completely new places, not just put new wallpaper on your bedroom. Sadly, I think we’ll be hearing much more about this bad idea when Apple’s new VR headset is announced, with a focus on mixed reality.

The even deeper questions for VR and AR are:

Is immersion a worthwhile goal at all?

Does immersion have to be “exactly like the real world” or something else?

By way of answering, the best VR experience I’ve had lately, where I lost myself in the game so completely that I walked into walls, is The Last Clockwinder. It presents a fairly small game world, but one that’s beautifully designed, and its puzzles are all about how you navigate that space down to the inch. Perhaps the least important thing about it is that it uses teleportation, but teleportation allows the game to focus on the things that matter.

In my experience, VR is better suited to exploring smaller environments in higher detail rather than traversing vast environments at high speed, as one might in a traditional screen-based adventure or RPG. Sure, if you have an entire empty basement to run around in, you might prefer your VR games use environmental redirection or redirected walking, but game developers like to make money and reach a big audience, which means catering for the majority of people with smaller play spaces. This is why I think upcoming advances in VR, like higher resolution, wider field of view, better controls, and lighter headsets, will make an outsize difference.

VR has dropped so far in the hype cycle that a lot of otherwise smart people have written it off entirely: “lol Meta sucks, no-one uses VR”, etc. This is like writing off smartphones because most people don’t like Windows Mobile or PalmPilot. That doesn’t mean I think Apple’s new headset will be the new iPhone; it’s more that VR and VR games are able to do important things that other hardware cannot.

One of those things is unparalleled visual and physical immersion. Unfortunately, the pursuit of immersion is leading VR game developers to the same artistic dead ends that other formerly-new media have faced and overcome. Eye of the Temple is an interesting experiment and an impressive effort from a solo developer, but it isn’t the way forward.