Finity

It's got the puzzle game juice

iPhone, iPad, Mac, Apple TV

Free with Apple Arcade

Endless

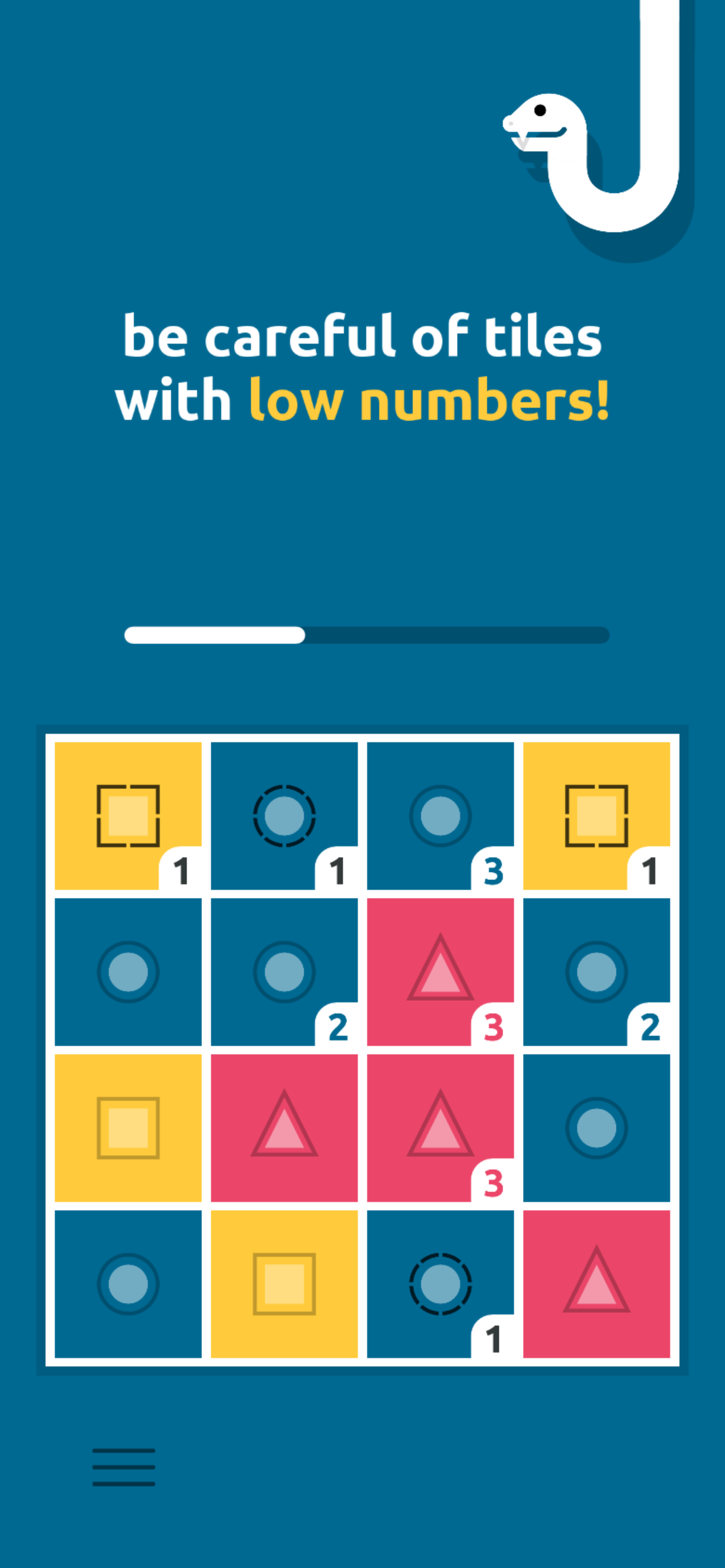

Finity is a puzzle game where you match three or four tiles of the same type in a row to clear them and earn points. Tiles are moved by sliding entire columns or rows; these wrap around the 4x4 grid, meaning that if you slide a triangle tile off the left of the grid, it’ll appear on the right.

Every tile in the grid has a number attached to it representing the number of times it can be moved (“move count”), so sliding a row depletes the numbers of all the tiles in that row. If you slide a tile horizontally when it has only one move left, its row will then be locked in place, becoming a “directional tile”. It can still slide vertically, but if you do that its column will be locked, too. The priority, then, is to:

Prioritise clearing tiles with low numbers lest they lock and make everything harder.

Match as many tiles at once, because if you only match three tiles per turn, you’ll still have a fourth whose number is going down (“Annual matches three tiles, annual deduction four tiles, result misery.”)

Clearing tiles fills a bar which, when full, moves you into the “level-up phase”. Each match during this phase earns you a “match counter”. These are exchanged into “level-up” tiles, and matching three level-up tiles completes the phase and starts the next level. This struck me as overly complicated the first time I played it, but the level-up phase is best understood as a way to accelerate player failure rather than have it drag out due to all your tiles getting locked up - it’s not too difficult to match any three tiles in normal play, but arranging three specific level-up tiles is considerably harder, especially when later levels increase the number of match counters required to earn a level-up tile.

Completing a few levels in a row increases your rank permanently, unlocking more complex game mechanics such as:

Matching four tiles increases the move count on all remaining tiles of that type

New tiles begin with two moves instead of three

Split tiles, where each half must be matched individually before it can be cleared

Connected tiles, where moving them might slide two columns or rows at the same time (i.e. lowering the move count on eight tiles instead of four)

Mystery tiles that need a tile dropped on top of them to reveal their type

“Power blocks” that can change tiles’ types, swap adjacent tiles, increase a tile’s move count, destroy a tile, etc. These are earned by matching tiles in normal play; you can have up to three at a time and the type of power block you get is selected randomly with a little slot machine animation.

I often forget how match three games like Finity are so much about luck, not just about what power block you’ll get, but which new tiles fill up the grid after you make a match. No doubt a truly horrendous amount of brainpower has been expended on perfecting the precise mix of new tiles to keep players hooked on Candy Crush and every other huge mobile match-three game out there (now more popularly known as “merge games”), and I’m sure Finity’s creators worked hard to keep things balanced too.

In Finity’s Classic mode, you can take as long as you like to figure out the optimal match, which is surprisingly tough at higher ranks when half your columns and rows are locked and you’re trying to get your final level-up tile. If this doesn’t sound appealing, the game eliminates overthinking in its Tempo mode, which introduces time pressure and a Rez-style soundtrack. A colour shade constantly ticks down from the top of the screen; when it reaches the bottom, it locks a tile or two. Matching tiles bumps the shade back up the screen a little and also gradually fills up your “lives”. When your grid inevitably locks up as things get faster, one of your three lives is consumed and every tile gets its number increased by two.

Tempo begins with an easy “finite” challenge where you only have to survive for a short time. Succeeding at this unlocks an endless “infinite” challenge that starts hard and gets even harder. I suspect this is the challenge players will keep coming back to in pursuit of ever-higher scores, especially since even a good run might only take a couple of minutes.

Despite its unforgiving difficulty, I found Tempo mode a welcome respite from Classic. In removing power blocks, connected tiles, split tiles, mystery tiles, and all the rest, it distills Finity into pure, frantic tile matching.

It’s not that I dislike those mechanics. It’s more that Finity is commendably uninterested in making things easy. Rather than occupying players with endless levels that unlock story or trinkets, Classic mode quickly gets so hard I imagine most players will abandon it after a couple of hours. Sure, it’s easy to begin with: a mere 90 minutes of play got me to Silver II rank, unlocking practically every mechanic I’ve mentioned. But getting to Silver III took another 90 minutes: my grids got gummed up whenever I couldn’t clear connected tiles quickly enough, and with seven levels to clear in a row, a single bit of bad luck was enough to put me all the way back.

My reward for getting through? Having to battle through nine levels to get to Gold I, this time with the infuriating mystery tiles in my way. I doubt I’ll bother when the faster, easier Tempo mode beckons, but I respect Finity for sticking to its guns on Classic. Since Apple Arcade reportedly pays developers based on how much time players spend in their games, they might be leaving a lot of money on the table.

From a game design perspective, Finity is the answer to the question, “what if you had a match-three game where tiles had limited moves?” Letting players slide individual tiles would be too easy, hence sliding entire rows and columns; and since most matches will be of three tiles, the grid size can’t be much bigger than 4x4 as you’d have too many non-matched tiles getting locked up too quickly. A larger grid might work if the “new tiles” algorithm was sufficiently generous, or if moves only reduced the count on a limited number of tiles instead of all tiles in the moved row/column, but Finity’s small size keeps players’ mental overhead low, crucial when you have so many literally interlocking mechanics working at once.

I’m no match three aficionado. Maybe Finity has been done before. Even so, it’s an elegant design, elevated with crisp icons, animations, and haptics. When you add Tempo mode’s music, everything thrums together in a way that makes Finity one of the most polished, juice-filled puzzle games I’ve seen in a long time.

Letter of Recommendation

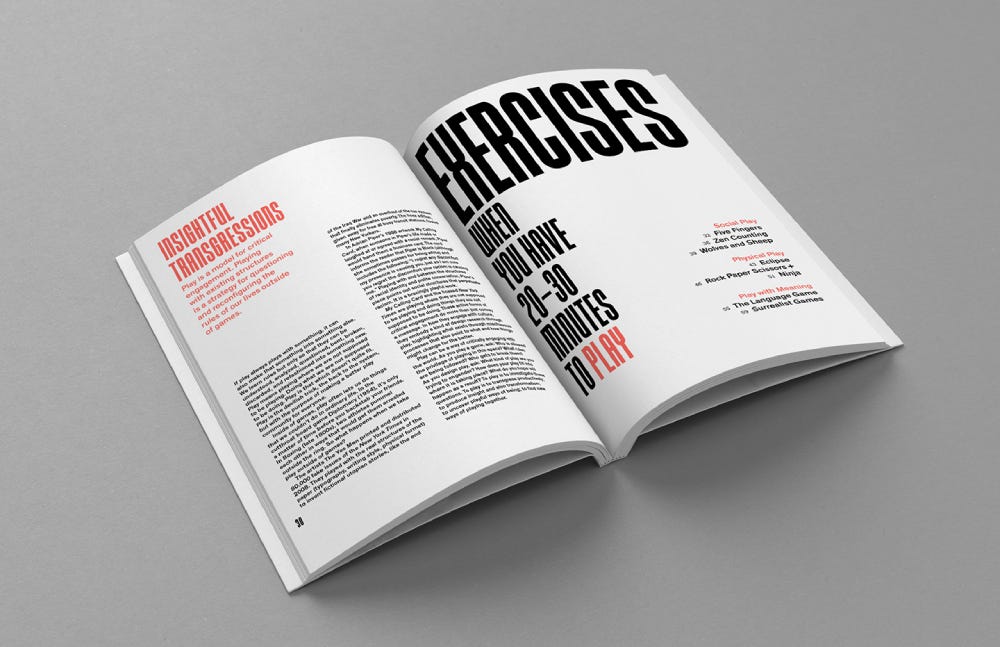

Last week, I ran a full-day workshop for arts students at MOME university in Budapest. If you’ve ever run a workshop, you’ll know just how much work this can be, so I was very glad to use the hands-on game design exercises from Eric Zimmerman’s excellent book The Rules We Break.

Here’s my schedule:

10:00am: 30 min discussion on the different kinds and definitions of games.

10:30am: Five Fingers, an ice-breaker game where everyone sits in a circle and people point at each other to “shoot” at each other and remove one of their five lives, as represented by the fingers held up on each person’s hand.

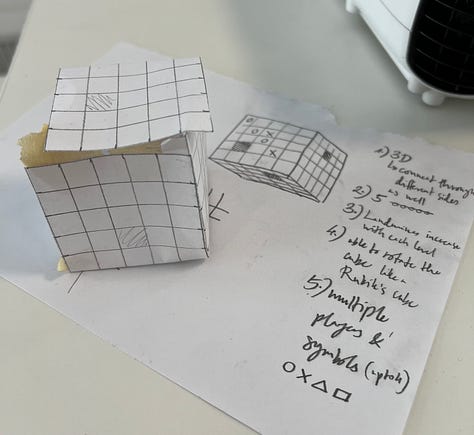

10:45am: Tic Tac Toe, where we discussed all the ways it can be modified (bigger grid, more symbols, time limit, more players, etc.) then split into groups to modify, playtest, and write down the rules to new games.

11:30am: Break

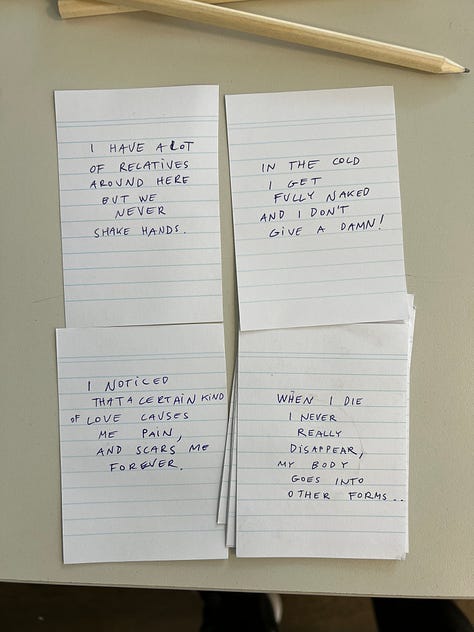

11:45am: A Deck of Stories, on writing randomly generated and procedural stories. Some really funny and touching stories came out of this exercise, impressive given English wasn’t most of the students’ native language.

12:45pm: Lunch

2:00pm: Bolf, on designing and balancing real-world physical puzzles (“golf but with beanbags”), concluding with a tournament where every group played each other’s holes. The most creative hole saw players watch videos on Instagram while throwing their bags ("a social commentary", more than one player remarked).

4:00pm: A Good Collaborator, brainstorming all the things that make someone a good person to work with

4:15pm: End!

It was a long day, but I enjoyed seeing just how imaginative the students were, and hopefully I helped them think of games as things that need to be played with.

And then I gave a talk about gamification at the Brain Bar conference!