Golden Idol Mysteries: The Spider of Lanka

Fill-in-the-blanks detective game extends the formula

PC, Steam Deck

$5.99 on Steam (requires base game for ~$15)

2 hours

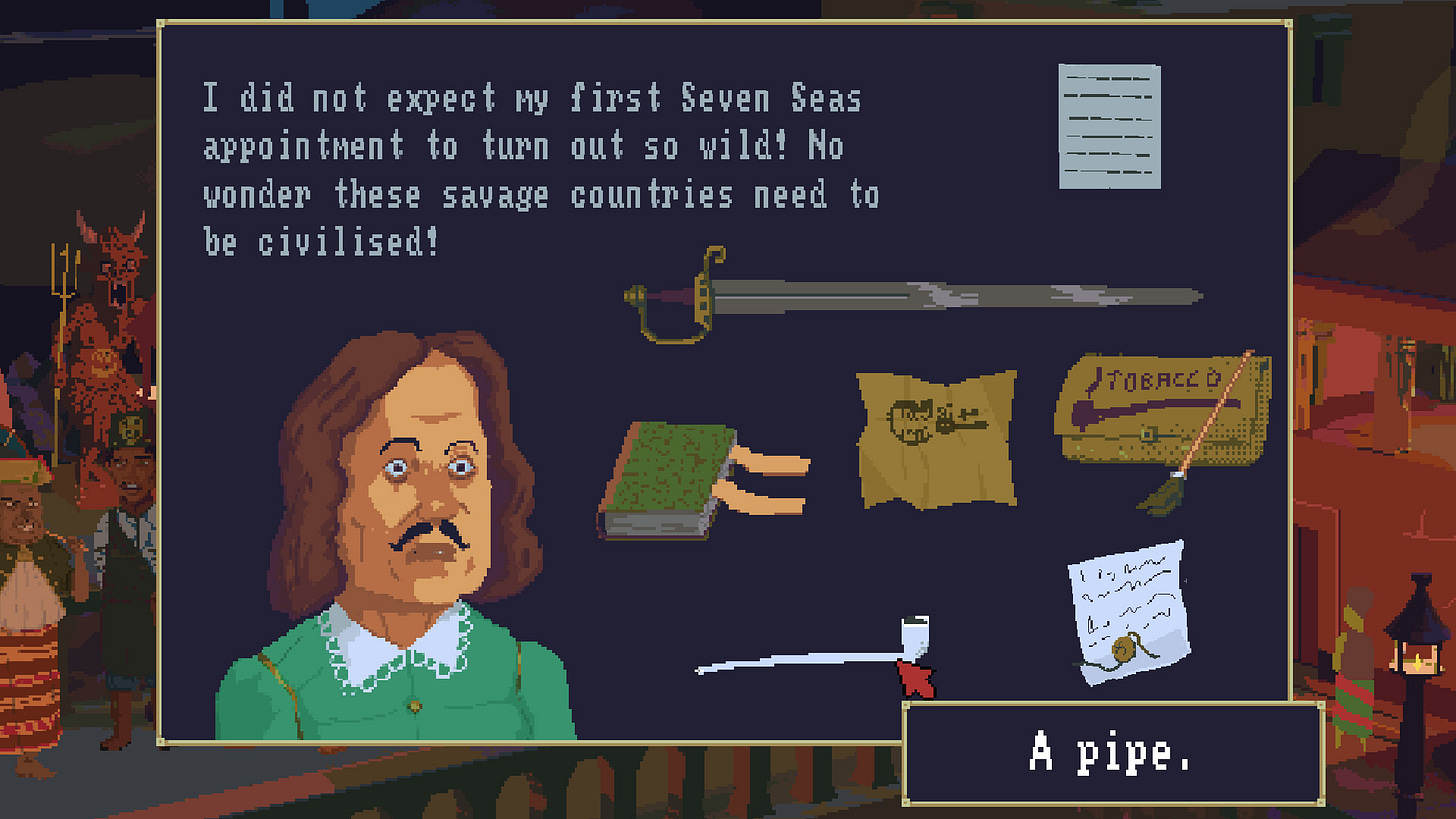

Golden Idol Mysteries: The Spider of Lanka is a paid addition (aka DLC, or “downloadable content”) to the detective game The Case of the Golden Idol. Like the original game, you solve a set of murders by investigating a freeze-frame of the scene. As you click on highlighted people and objects and text, like in a graphic adventure game, you collect different types of words; so, clicking on a surgical kit will collect “scalpel” (an object) and “treated” (a verb).

The Spider of Lanka’s story sees you unravel a colourful, murderous conspiracy set in 1741 in the Kingdom of Lanka, a fictional South Asian location, featuring spies, priests, lovers, soldiers, and the greedy Seven Seas Company. Everyone’s sending letters and secret messages to each other; half the people are armed to the teeth with swords and pistols; betrayals and poisons and cryptic codes abound. The game’s bright retro 2D graphics, with the occasional bit of shiny, shaky lo-fi 3D art reminiscent of Myst, are perfect for the game’s heightened fantasy.

Once you’ve collected all the name/object/verb words in a scene, you should have a reasonable idea of what went down and can move from the Exploring mode, where you’re looking around the world, to the Thinking mode, where you’re solving the murder(s). Murders are solved by filling in the blanks in a series of questions or statements using the words you’ve collected:

There are multiple things to solve, some of which are harder than others. I found that figuring out people’s identities is a good place to start, since you can operate by process of elimination. When that’s done, you can have a decent stab at the “narrative” statement where you describe how and why the murder went down. Crucially, the game will tell you if you’re close to a solution (specifically, if you have two or fewer incorrect words), so you don’t get disheartened or waste too much time.

Solving murders requires a pleasingly close observation of the scene, like which side of someone’s head is injured, who they’re sitting next to, what they’re holding in their hand, whether the letter in their jacket pocket has an unusual symbol, and so on. It’s not quite at the level where you need to keep copious notes of your own but it gets close, especially in later scenes with multiple rooms or areas you can zoom into or “visit”. Working out someone’s identity involves an intuitive chain of deduction – “if she’s still alive, she must be one of these three people, and only two of them are wearing the hat we saw in the spy’s diary” etc. – that also suits “couch co-op” play, where one person holds the controller and others theorise. It’s fun!

There are only three scenes in The Spider of Lanka, however, while the original game had twelve murder investigations. Story-wise, this isn’t ideal since the first two investigations, while dramatic (the first is in a gambling den where everyone’s killed each other), don’t present an enticing mystery to unravel, and it’s only by the end that things really make sense. The original had a quicker start – a treasure map, a mysterious golden idol, a man bursting into flames, etc. – that soon expanded into a lurid, utterly bonkers, multi-decade conspiracy.

I can’t say I was too disappointed, as the game developers worked very hard to convey The Spider of Lanka’s bite size nature. It costs a third of the original and you get about a third of the content; and if you liked the original (which is required to play this add-on,) you’ll like more of the same.

At this point, the discussion leads into our own fill-in-the-blank puzzle, the solution to which reveals a lot about how we think about games today:

The Spider of Lanka is a _______ [soulless cash grab] [continuation of a beloved game]

What does this game add to the original? _______

This is particularly relevant because The Spider of Lanka, like the original, is so simple, mechanically-speaking, that you could design every scene and in fact the entire game by drawing it on a piece of paper. Literally, you could just draw all the characters and have little boxes for what they have in their pockets; underline all the things that should be collectible words; annotate anything that needs to be animated in a loop; connect different areas with arrows; and have a separate piece of paper with the solutions. There are no choices to make, no branching pathways, no conditional states – it really is just like a puzzle book, except that it’s much more pleasant to use and keeps track of your answers automatically.

So, the answer to the second question is: absolutely nothing from a mechanical perspective, but absolutely everything from story and puzzle perspective, just like how the book Through the Looking Glass remains exactly the same kind of book containing printed words and pictures as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, but those words and pictures are all completely different. Whether you find that a satisfying answer depends on whether you think games must innovate their technology and mechanics in order to be “better” than what came before.

Unsurprisingly, I don’t think they do. What’s more, I think it’s good that they don’t, because there are different kinds of innovations that we should care about when it comes to games.

The Case of the Golden Idol was directly inspired by Lucas Pope’s Return of the Obra Dinn. Obra Dinn, as most people call it, pioneered the “fill in the blanks to solve a murder based on clues the environment” format, a format that delivered the most fun and most thoughtful detective game I’ve seen in years. Fans begged for more games like it, and The Case of the Golden Idol delivered (as did Rivals). Golden Idol itself created a narrower format (2D graphics, no voice acting) that was easier to produce and copy, which the developers are clearly extending – that’s why it’s called “Golden Idol Mysteries”) – and I hope others copy, too.

In other words, Obra Dinn and its spiritual successors (“Obra-likes”) aren’t simply in the same genre of detective games, they represent a new format of game.

I often tell people that making a game is just like making a movie except you have to invent new, better cameras and lights every single time. This is what’s propelled games to new heights of graphical and audio realism and interactivity. It’s also what makes game development so exhausting and unpredictable. It’s been going on for so long – half a century – that people think that technological innovation is an inextricable part of successful game development. But it doesn’t have to be.

We’re at a point where certain formats are good enough – platformers are a good example, and Obra-likes might be another. We should welcome more formats and more non-technical and non-mechanical innovation within existing lines, which some might call “copying” but I think most would recognise as “more of a good thing”. This doesn’t mean I welcome Call of Duty 17, but we should be glad when formats appear that are manipulable and can be taken in interesting new directions by people who aren’t technical wizards.

I can think of half a dozen ways to iterate on Golden Idol’s format without changing a single bit of core programming, whether that’s story or characters or puzzles or level size. We already have video games that do the same thing forever but with new variations and stories and settings, they’re incredibly popular with loyal audiences, and they’re usually, somewhat derisively, called “casual games”. We also have incredibly popular formats that barely ever change, like books, songs, movies, and crosswords; as games mature, the same will happen too, but because games are such a capacious form of art, that process will look more like entire new genres and formats being spun off rather than games becoming ossified as a whole.

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that The Spider of Lanka chose an anti-colonialist story that depicts indigenous people as smart and complex, rather than the original game. It’s the success of that original game, and of Obra Dinn, and of the affection towards the format as a whole, that may have given its creators the confidence to try something different. As long as they keep making these games, I’ll keep playing.