PlayStation 5

$69.99

20 hours long

Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 is an action-adventure game where you play as Peter Parker and Miles Morales as two Spider-Men protecting New York against villains large and small, amidst personal and relationship drama. Combat and traversal form the core gameplay, but it’s the slower and more heartfelt moments that elevate the game beyond a technical marvel.

Disclaimer: While I’m the producer and lead designer of Marvel Move, I’m writing this in a strictly personal capacity. Of course I can’t pretend I’m unbiased but “Spider-Man 2 is a good game” isn’t an unusual opinion amongst games writers!

Most missions and sidequests take place in specific locations throughout New York City. You reach them by swinging between skyscrapers with your web shooters, which instantly fire webs to appropriate locations above and ahead of you. We’ve all seen this in the movies but it remains astonishing how easy and natural it feels in this game; in practice you’re holding down one or two buttons and nudging an analog stick, yet the adrenaline rush of always being slightly out of control, like on a playground swing that’s been pushed a little too hard, never diminishes.

It’s easily the most joyful form of traversal I have experienced in any game, which I attribute to its combination of real(ish) physics in a 3D world with meaningfully varied elevation. It’s so good I’m baffled why it hasn’t been ripped off more; grappling hooks and grapnel launchers are common in action adventures, but using them as a primary traversal mode is unusual.

Spider-Man 2 introduces Web Wings, wind tunnels, and updrafts so you can glide when there aren’t any tall buildings around (e.g. across Central Park). They’re fine, I guess? At the beginning of the game you can’t glide very far, which is frustrating, and even when upgraded the wings are more utilitarian than fun. Unsurprisingly, Spider-Man is best when he’s swinging, though it is nice to see New York from high up.

Once you’ve reached an area of interest, you will do one of three things, in descending order of frequency:

Punch villains

Look for a thing

Walk and talk to friends

The first two – especially combat – make heavy use of Spider-Man’s web powers. These can variously be used to hit things at a distance, bring distant things towards you, throw things, and move things towards other things. In other words, they allow you to perform actions at a distance, which is most of the appeal of guns but even better, because they are ostensibly non-lethal and are more versatile.

Like traversal, this feels amazing. The kinetic pleasure in snatching a Spider-Bot towards you from twenty meters away or zipping through a gap in a wall is unmatched. You see something in the world, you want to do something with it fast, and Spider-Man’s skill set means you don’t need to wait a second. Web powers reduce the gap between thinking and doing, intention and action. Again, why don’t more games do this?

The combat is less compelling. There are lots of things you can do, like dodge, punch, shoot webs at enemies, yank them towards you, and so on, but their identikit powers and behaviour and the arena-like combat environments quickly become repetitive. At its worst, combat is a slog through waves of enemies and bosses with multiple health bars you gradually whittle down by dodging attacks and punching them more. Confined to a rooftop or an indoor hall, Spider-Man becomes indistinguishable from other melee games, and as fights lengthen, the game’s constant dialogue becomes a liability rather than a strength.

This repetitiveness is leavened somewhat by special powers that recharge over time. These include four “ability” slots associated with Peter’s robot arms and Miles’ electric powers, corresponding to a charge, big punch, lifting enemies into the air, and so on – vanilla stuff. Then there are four “gadget” slots shared between the two characters, for things like a web grabber that pulls groups of enemies and junk together, and a sonic blast. These can all be upgraded and can change when Peter gets alien-enhanced powers, and so on. Oh, and there’s a special “symbiotic surge” and “mega Venom blast” that enhances Peter’s damage and blows stuff up near Miles, respectively.

All these powers, plus the finishing moves, gives you the sensation of being super powered even as you engage in low level battles with random hoodlums, but aside from their visual spectacle, I appreciated them mostly as a way to get combat over with quickly rather than being especially enjoyable to use (except for the web grabber, whose physicality never disappointed).

My problem with Spider-Man 2’s combat is that it sits in an uncomfortable zone between being highly scripted and being more free-form. The former is exemplified by the game’s numerous cutscenes and chase scenes where you press buttons in exhilarating quick time events (QTEs) to catch falling civilians or punch bosses; the latter doesn’t really exist in the game but might be equivalent to Soulslikes or Breath of the Wild or first-person shooters whose combat encourages you to do more or less anything.

Both can be done well, but sitting in the middle feels unsatisfying, which really gets to the tension at the heart of Spider-Man 2 – is this trying to be a movie or a game?

This was a very persistent and annoying question during the 2000s and 2010s whose roots I will not get into but is valid here because Spider-Man 2 is both:

The most movie-like game ever made due to its incredible graphics, cinematic cutscenes, and linear storytelling and

A highly accomplished game qua game thanks to its astonishingly good traversal and vast “open” world

Now, you could say the same thing about Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead Redemption 2, but the difference is that Spider-Man is one of the most famous fictional characters in modern history, and with great name recognition comes great responsibility. You cannot make a Spider-Man game where players have the choice to go around murdering people with guns; you cannot tell a story without some combination of Mary Jane, Harry Osborn, Doc Ock, Green Goblin; you cannot take away Peter’s web swinging powers.

Spider-Man is a known person, like Sherlock Holmes and James Bond. Games with such characters operate within strict parameters. There’s always freedom to try new things but you have to hit the main beats of their story; even Across the Spider-Verse with its critique of “canon events” can only change its Spider-Man’s character and backstory and abilities so much. It would be a fascinating exercise for students to design a Spider-Man game that breaks the mould, but it would be an extraordinary financial risk for a publisher.

Spider-Man 2 needs combat that at least feels freeform, because that’s what players expect from a big-budget game today. The combat also needs to be cinematic, because Spider-Man is a movie star, and integrated into cutscenes that seamlessly take you from one encounter to the next; that’s why it’s confined to arenas and rooftops.

There’s a moment early on when you’re battling lots of mini-Sandmans (Sandmen?) in various arenas. It’s not terribly interesting from a combat perspective – they’re all the same. Later on, you can perform an action to break apart pipes to “melt” nearby sand and reveal whatever’s buried beneath. It’s a cool look, even if it makes no sense. Because Spider-Man 2 isn’t a true open world, you can’t perform this on pipes everywhere – it only works in certain places. This happens over and over again to the point where cutscenes with QTEs blend into highly linear gameplay situations with dazzling one-off actions, like when you fire a Iron Man-style beam weapon to cleave Sandman in two.

Sometimes these moments feel a bit much, more like tech demos than anything else, like when Sandman punches you across twenty blocks and you zip back within seconds, all thanks to the PlayStation 5’s fast SSD. It’s all scripted, just like a bravura sequence where you swing through portals across New York, but who’s expecting choice in a Spider-Man game?

The actual structure of the game is pretty conventional. While you swing around town, icons for random encounters will pop up in your view, like Arms Deals or Arson. When you arrive, you invariably beat everyone up and take civilians to nearby ambulances. Sometimes the other Spider-Man will be there and you’ll do fun combo takedowns.

Stopping crimes and taking photos or finding hidden Spider-Bots or completing sidequests earns you “district progress”. There are 14 districts with their own reward tiers, giving you the ability to “fast travel” within them, along with Tech Parts and Hero Tokens that improve your gadgets, health, speed, abilities and so on. You also get experience points (XP) doing most things; when you have enough XP, you’ll level up and get a Skill Point to learn new abilities and moves. Levelling is fairly constant and I never felt the urge to grind sidequests for XP; maybe that’s because I turned the difficulty down, but hey, that’s a good thing!

As the story progresses and you meet new enemies, more encounters appear on the map – Kraven’s Hunter outposts, cultists, alien symbiote nests, and so on. This makes things blissfully calm at the beginning of the game and rather silly by the end when they’re all crammed in together.

Occasionally the game does very contrived things like “if you find all the crystals that are affecting Sandman, you could help him become whole again” or “we need to restore network access to New York” and you just know it’s going to unveil twenty identical sidequests (optional, thankfully) to get all of Sandman’s memories or such. But on the whole, it’s astonishing how much unique stuff there is, how constantly novel sidequests appear. As Miles, I helped a student stage an elaborate prom invitation to his boyfriend, which was unbearably sweet; another time, I tracked down a “monster” in Brooklyn that turned out to be an injured robot dog drone; naturally, I had to beat up the baddies who hurt it.

Spider-Man is defined by his wholesomeness and pluck; without it, his story would be one of unremitting violence. This game forgets this lesson too often, though.

After battling Sandman, we’re introduced to Harry Osborn, Peter’s best friend, whose illness has been healed by an exoskeleton that later turns out to be an alien symbiote. Harry invites Peter to join him at a new institute aiming to save the world. You wander around the institute marvelling at how Science could prevent famine and save the bees and whatnot, which inevitably gets undone as various baddies intrude, but you’re left with the impression that otherwise they would have saved the world. This kind of tech solutionism is hardly new, but it’s a shame to see it presented so uncritically here, and you can’t just say “oh it’s a comic book” because comic books have criticised it!

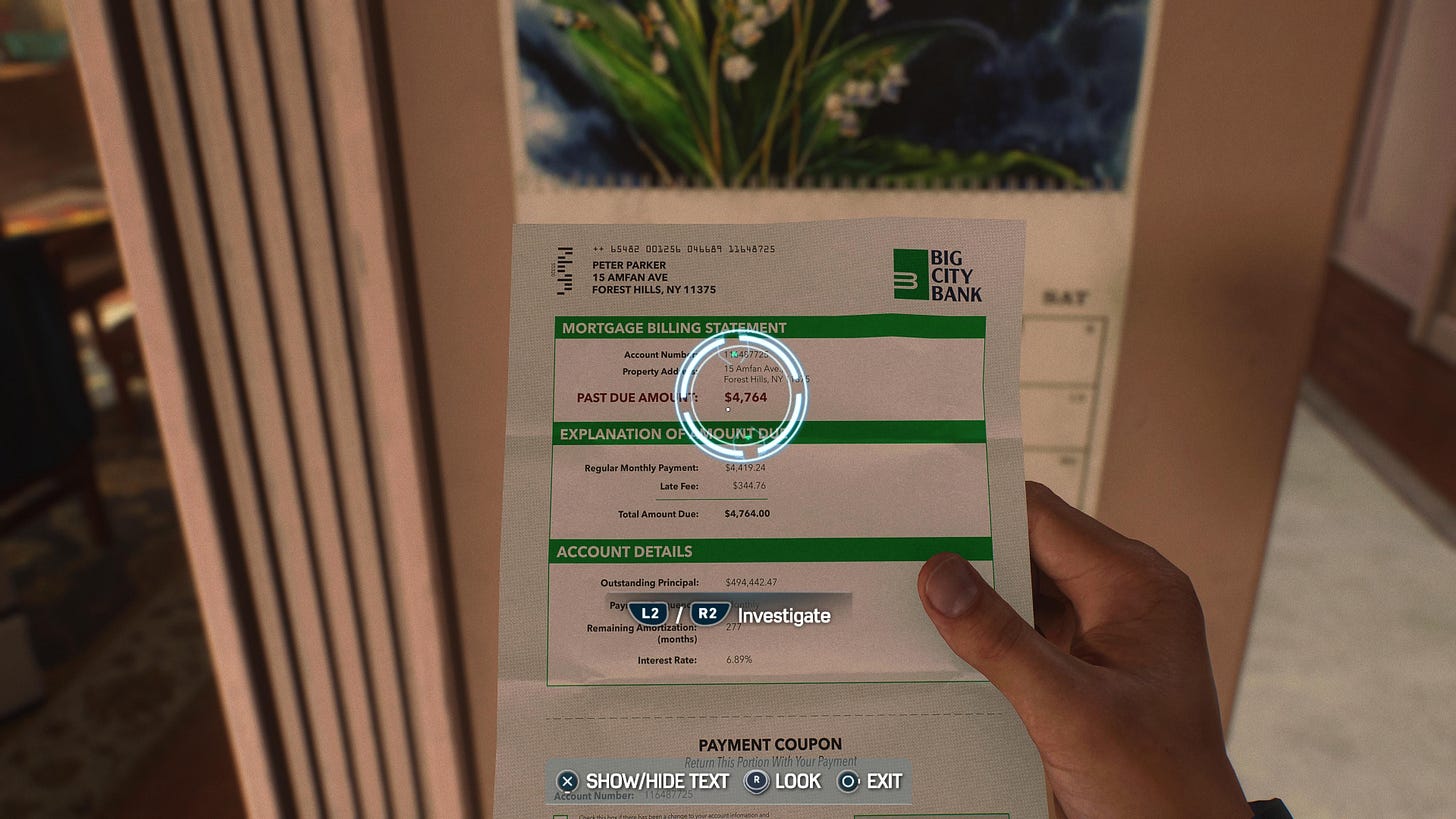

In any case: it’s wholesome. There’s no combat at all, just walking around looking at things (a walking simulator bit). These moments happens quite a bit early on, like when you tidy up Peter’s house and look at overdue bills and old photos, or cycling through town with Harry, sneaking into your old school and shooting hoops to music from The Shins (yes, for real). Probably the most impressive bit comes halfway through the game in Coney Island, where you play a truly astounding number of fairground games, all while chatting to Mary Jane and Harry.

Between these and the countless puzzles and one-off interactions threaded into sidequests and the main story, Spider-Man 2 must have the highest density of minigames I’ve ever seen in a long time. There’s a rhythm game in a VR attraction, a game where you launch drones in the sky, a puzzle game to analyse molecules, even a bee protection minigame! None of them are very fun and they’re all skippable, which raises the question: why do they even exist?

The answer is that Spider-Man 2 is not an action-adventure game: it’s a Spider-Man simulation game. You get to be Spider-Man, and that means worrying about the mortgage and riding rollercoasters and looking through microscopes. It’s a superhero life simulator, enabled by a 20 hour duration, a near-limitless production budget, and not one but two Spider-Men, each with their own personal drama.

Unfortunately, around the midpoint of the game, things get less wholesome and the story accordingly becomes unremittingly grim and violent. A super-strong villain, Kraven the Hunter, arrives in New York, frees lots of imprisoned baddies merely so he can hunt them down. Like an annoying version of Batman, Kraven is always one step ahead of our heroes, meaning you battle him over and over again because he’s constantly allowed to escape.

Kraven is ultimately killed by Venom, a new villain created when the alien symbiote fully takes over Harry. In fact, you get to play as Venom and kill Kraven during a disturbing sequence where you mow down dozens of security guards. Venom then becomes the main antagonist and, yet again, you fight him in battles where he has multiple health bars, prolonging the endless monologuing: “you’re still holding back”, “you’re too weak”, etc.

What works across a few lines in a short movie fight scene simply does not work when spread across dozens of lines in a minutes-long boss battle. The dialogue when you fight an evil version of Mary Jane is especially ill-advised. It’s not as if the creators don’t know how to write her – she sounds fine in other scenes – it’s just that if you want Peter to have an argument with Mary Jane, it doesn’t need to involve them punching each other.

Case in point: the multiple dream sequences where Peter and Miles literally battle their inner demons. I am officially requesting the game designers of the world swear off this trope! We’ve spent the entire game punching people, is it not possible to confront your fears in some other way? Demolishing dozens of enemies at a time is not what I associate with Spider-Man – let’s leave that to Batman and Wolverine, please.

Combat aside, Spider-Man 2 is a marvel. It’s unblighted by gamification, polished to a mirror-finish, wholesome to a fault, with the best traversal ever invented. There is no finer cinematic game. They could make a new one every five years – hell, every single years – and players would gladly keep buying them as long as there’s more story and more villains.

Maybe that’s fine! Maybe we’ve reached the point of technological maturity in video games where the yearly gains in graphics and performance shrink to the point where players’ demand for innovation and novelty will have to be sated in other ways. Who knows, maybe Spider-Man 3’s innovation will be breaking its gameplay canon?