Tabletop game

$39.99

4-6 hours

Mother of Frankenstein: Volume One is a tabletop puzzle game where you read letters, decode star charts, and solve riddles to reveal a secret hidden by Mary Shelley. While it shares the tactility of other “escape room in a box” games like EXIT: The Game, Unlock!, not to mention Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective, its subject and length – 15 hours, if you count all three volumes – makes it feel weightier than the rest.

A sheet titled “Start Here” tells us to:

Think of [Mother of Frankenstein] less as a puzzle game and more as a novella with puzzles: instead of trying to get to the end as quickly as possible, we recommend you take your time to engage with the story.

While Volume One has more writing than similar games I’ve played (excepting Sherlock Holmes), I wouldn’t call it a “novella with puzzles” but more “a puzzle game with story” because even with fifteen letters, there’s not all that much of it. Those letters deftly conceal clues within their prose, making for an unusually hurried reading experience as I hunted for solutions despite the instruction to take our time. I suspect other players are more patient, but the fact the game mentions pacing at all suggests the designers are aware of the hazard.

I was patient in one way: the game advises that if you’re stuck for more than 15 minutes, you should consult their free online hint system or paid hint cards – and we never resorted to them until the very end…

I was given a free review copy of Mother of Frankenstein Vol 1-3.

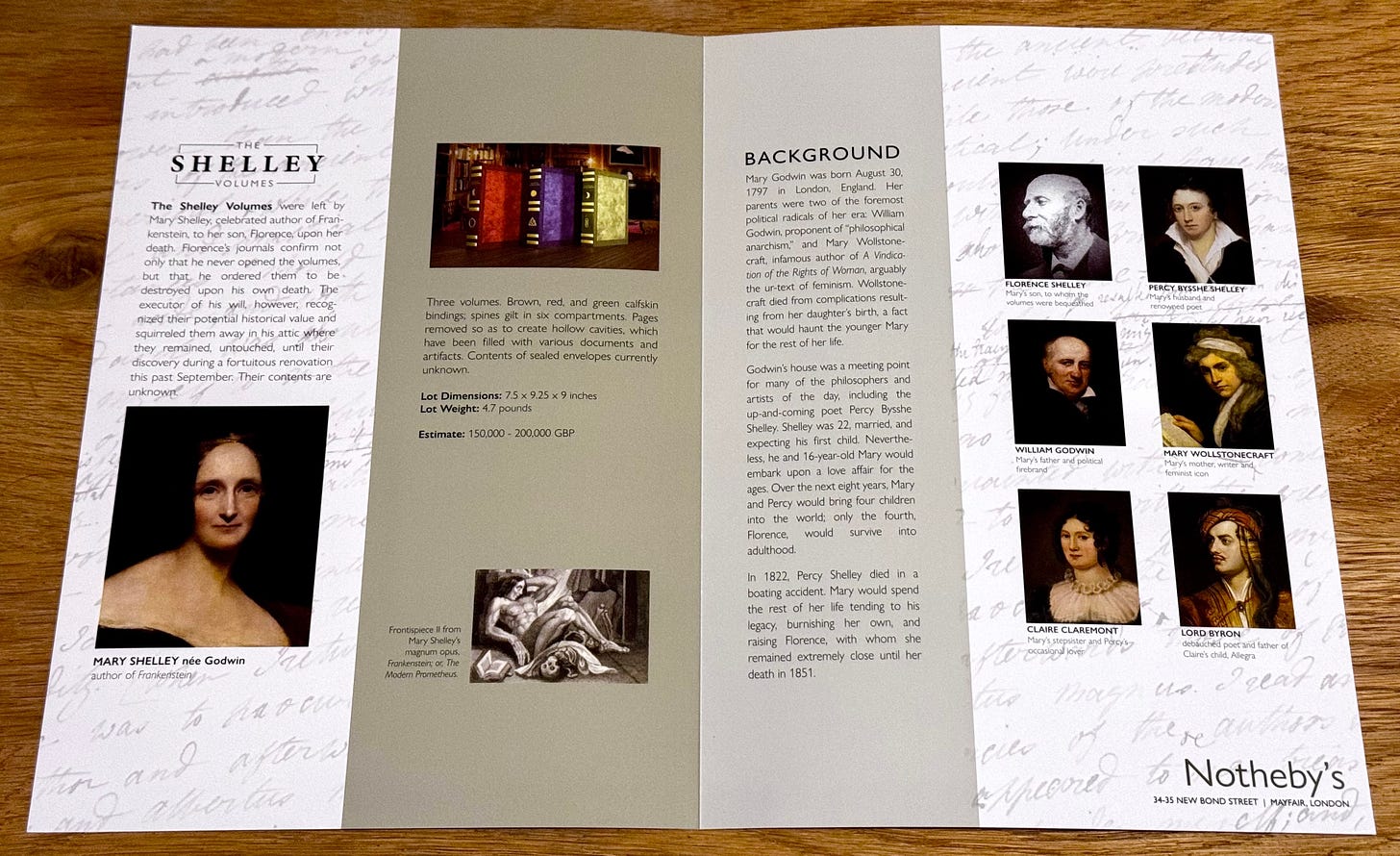

Mother of Frankenstein’s conceit is that you’ve won an auction for “The Shelley Volumes”, three volumes filled with unknown documents and various artefacts. These were left to Mary Shelley’s son, Florence, upon her death, who himself ordered them destroyed upon his own death, but were instead preserved. This setup is conveyed by a fine imitation of an auction brochure from “Notheby’s”, which also includes a brief biography for Mary Godwin, as she was known before her marriage to Percy Bysshe Shelley

Then we have Mary’s letter to Florence. She writes that within the three volumes is “a secret many great men have devoted their lives to unearthing, and always in vain”, one that now belongs to him as a family legacy. This vague intrigue is all you get to propel you, which, owing to its studied vagueness, fell flat for me; not that I threw away the game at that moment, but what drove me instead was my curiosity of reading the letters and the satisfaction of solving puzzles.

Those puzzles exist because Mary has literally designed them as a way to prepare Florence for his secret legacy. As narrative justifications go, it’s a pretty good one! This first volume covers her courtship with Percy Bysshe Shelley, she explains, consisting of three assignments on astronomy, poetry, and music. Completing each assignment gives instructions on how to assemble a larger ring-shape puzzle; those rings, combined with riddles spread across fifteen letters between Mary and Percy, spells out a phrase marking the end of Volume One. Mary’s instructions are unavoidably detailed and a little daunting, but I suppose if you’ve gotten this far you’re not going to leave.

Astronomy

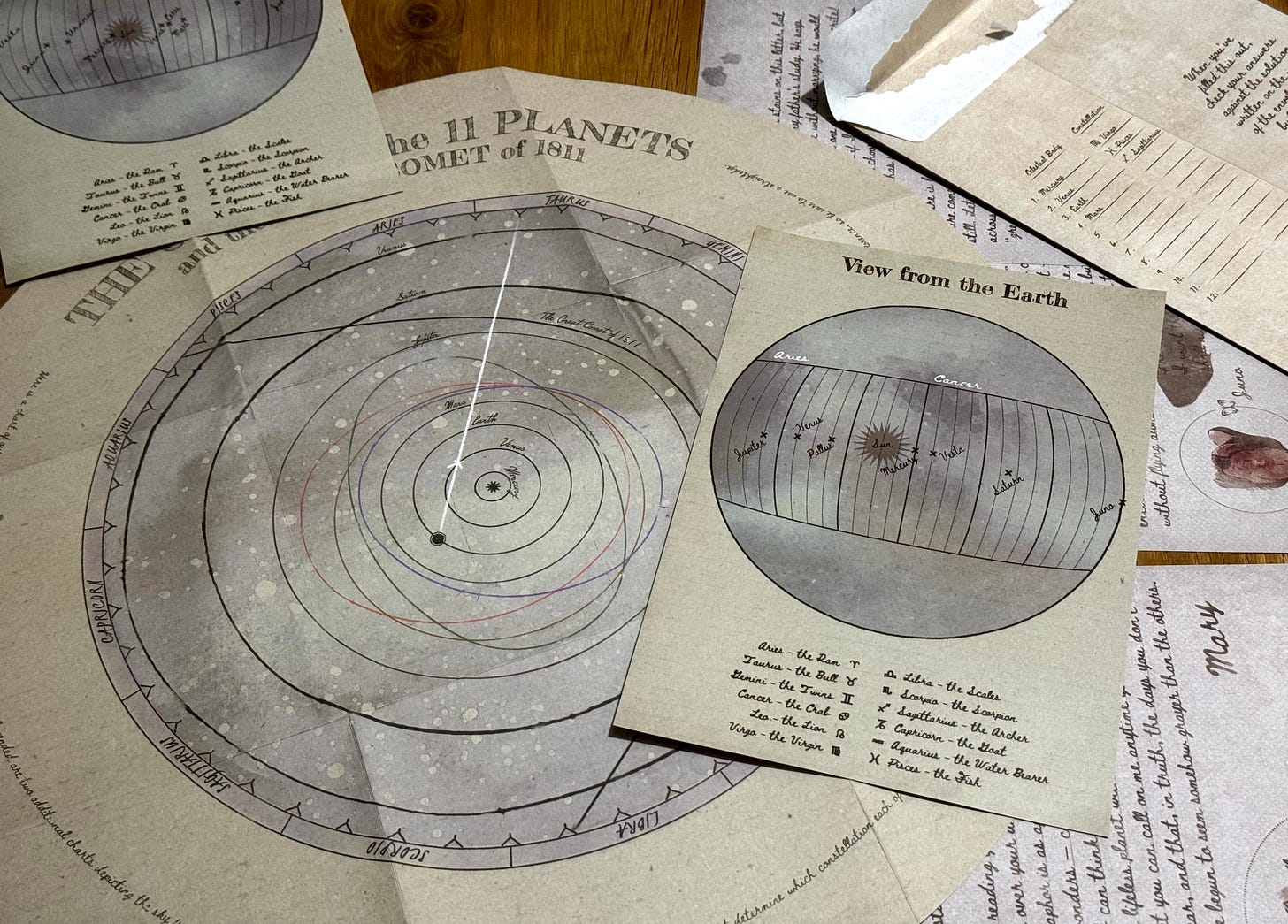

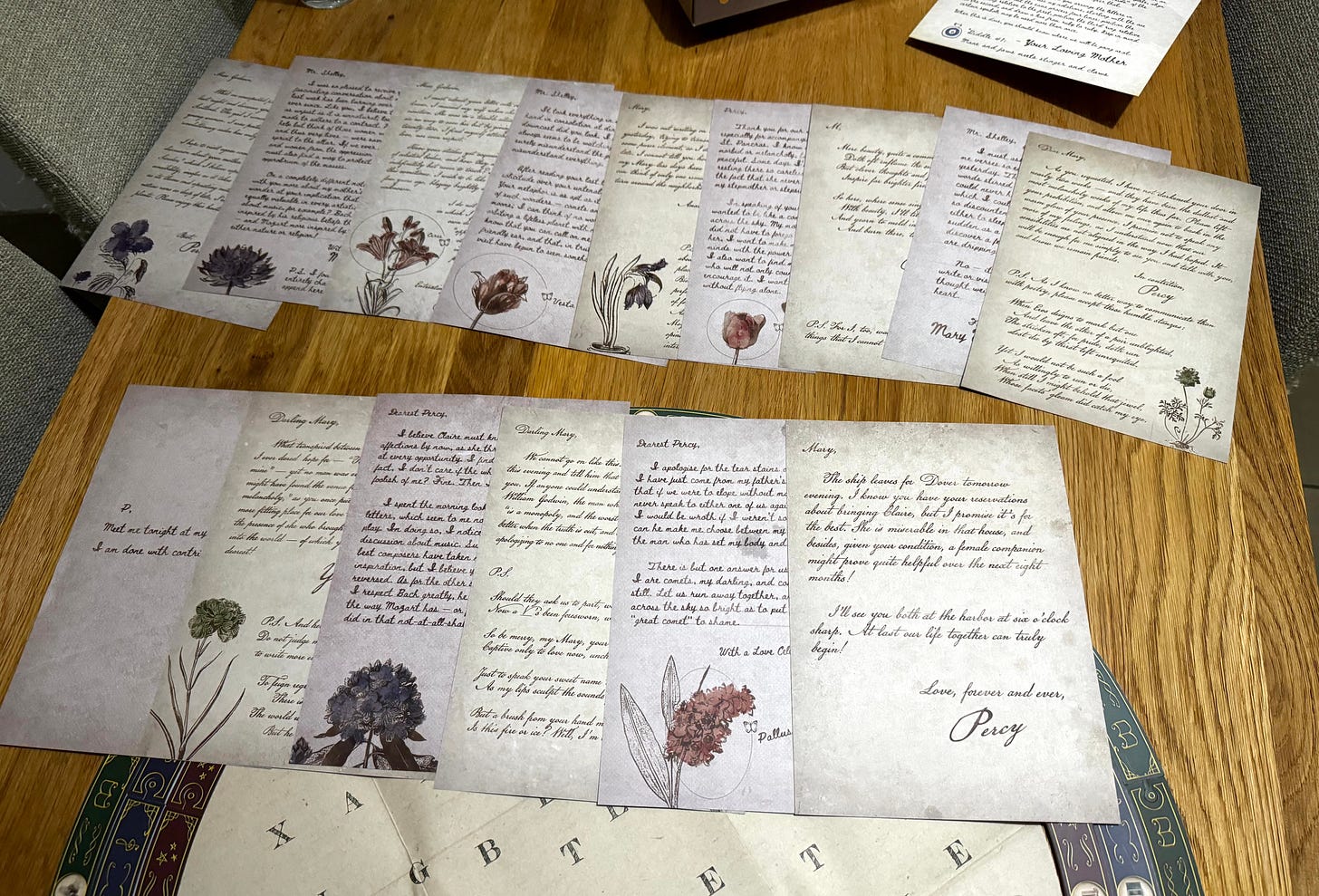

Each assignment comes in a sealed envelope, and Astronomy consisted of five letters, two maps of the stars, and a big map of the solar system.

The letters detail Mary and Percy’s burgeoning relationship. Percy visits her father and unexpectedly meets Mary, recently returned from Scotland. It’s an intellectual connection as much as a romantic one, discussing astronomy, nature, physics, and – uh oh – the “unjust” and “unnatural” institution of marriage, which is just as well since Percy already has a wife.

We first tried putting the letters in order based on references to events and how they addressed each other (“Mr. Shelley” then “Percy” then “Dearest Percy” etc.) until we realised a) we didn’t have all the letters yet and b) their order was irrelevant for now. In fact, the back of every single letter had both a fragment of a riddle and a tiresome if necessary warning to “not try to solve these riddles until all three rings have been constructed”.

Our actual goal was to mark the position of each planet and four asteroids on the map of the solar system by means of triangulation from the two maps of the stars: one from Earth and the other from a comet. In practice, this meant drawing lots of intersecting lines across the map, a nice spatial reasoning puzzle that also involved deduction, since the orbits of the asteroids were unlabelled.

With this done, we wrote down the “answers” (the order of the twelve planets and stars, plus which astrological sign they were in) on the back of the envelope, then checked whether we were right by peeking inside the envelope where the correct answers were printed. This clever bit of design saved us from opening it up again when we came to assembling the ring for the final puzzle.

This took about 50 minutes, so we had time to move on to…

Poetry

Our mission: write out the “order” of twelve poems spread across five letters and seven accompanying sheets. I’ll spare you spoilers and simply note that this involved the most wordplay I’ve seen in a narrative puzzle game. Some of the answers were simultaneously groan-worthy and delightful in the best possible way, and the overall puzzle was constructed such that you were aided on the final tricky questions by means of elimination.

Good stuff! This took 40 minutes, making for 1.5 hours in total for our first session.

Music

The “Start Here” sheet advised us to tackle this assignment in its own session, but in the end we only spent an hour. I’m sure this was because we were both experienced at reading sheet music, which lay at the heart of this puzzle.

Once again, we had to put twelve things in order – this time, songs. Three “Exercises” guided us through this process, the first two involving the completion of magic squares based on the number of beats in a sequence of notes and rests from the songs, and the third requiring a close reading of the five letters in the envelope.

The magic squares were designed with just the right level of complexity where certain answers seem impossible to reach until you realise you can, e.g., figure out some based on elimination, or that diagonals in magic squares behave the same as rows and columns. The same went for matching the songs with symbols, which called for yet more wordplay.

We were less enamoured of the third Exercise where we had to rank Mary’s preferences of four philosophical concepts; essentially it was a logic puzzle but written in prose, making it more than a bit ambiguous to the point where when we discovered we’d mis-ranked one concept, we simply threw up our hands and moved on. Such are the risks of narrative puzzles!

Letters

With the assignments completed, we assembled three concentric rings out of twelve pieces each, their order corresponding to the answers we’d written on the back of each envelope, and placed the reverse side of map of the solar system in the centre. Next, we put all fifteen letters in chronological order and flipped them over to show a set of three riddles. This was a bit awkward with only two people reading through the letters, so I shudder to think how much fun it’d be with any more…

Each riddle came in two parts. The first revealed how the middle and outer rings of should be rotated to align different symbols; the second revealed which two symbols on the circular sheet should be connected in a line to intersect with letters that combined to form the final phrase. The rings were a bit tricky to rotate without falling apart or everything getting out of alignment, but at least they were impressively large and chunky.

As for the riddles, they were straightforward except for when they weren’t; it’s a rare riddle that doesn’t have multiple acceptable answers, even if one is better than the others. One riddle spoke of a “hungry creature” which prompted much debate about which of a whale, bear, bee, fly, soldier, or increasingly metaphysical entities might hunger for things. In the end, we solved all the riddles but the last, and we only realised we were wrong because the letters it generated were gibberish; on learning the correct answer, we were both very much grumpily “oh I suppose that one works better.”

This points to a hazard in so many physical puzzle games, which is if you reach the end of a multi-step puzzle and get the wrong answer, it’s often unclear exactly where you went astray, and it’s frustrating to backtrack and physically “fix” the error. This is less of a problem in video games which can tell you when you’ve made a mistake in real time or reveal which sub-puzzle you got wrong. Mother of Frankenstein has a hint system, of course, but I couldn’t help but think of it as a failure to resort to it.

EXIT: The Game addresses this with its puzzle cards and physical decoder wheel, an innovation that lets players quickly check whether their answer is correct without risk of spoilers, and even better, guides players toward the correct solution; I believe Unlock! does a same thing. These ingenious “answer validation” systems limit puzzle design due to how they require answers to be represented as numbers or symbols, in the process making the whole game more visually cluttered, but their popularity indicates that for most players, the saving in frustration outweighs the costs. I don’t think Mother of Frankenstein needs a better answer validation system; for the most part, its puzzles are very well-designed. It’s just that that people tend to remember the frustrating sections more than the other bits.

After 90 minutes in this session and four hours in total, we were all done with Volume One. Puzzle-wise, I enjoyed the experience and especially the wordplay, something rarely seen in these kinds of games.

I was a little impatient with the story’s pacing, however. I get that not everyone is as interested in plot as I am, but given that the entire reason Mary made such an elaborate puzzle was to hide an awesome secret, I would’ve appreciated having more revealed after four hours of effort. Perhaps Volumes Two and Three will change my mind – we will see.

This lack of urgency touches on a wider problem with Mother of Frankenstein. As a whole – the letters, the box art, the name, the marketing – the game does a very poor job of explaining why players should care other than unearthing a “secret”. Don’t get me wrong, it’s refreshing to play a tabletop puzzle game that isn’t about murders, kidnappings, or theft. I can’t praise the designers enough for telling a very different kind of story, one with consistently solid writing where Mary’s curiosity and intelligence shines through. It’s clearly a labour of love given that Mary Shelley is not anyone’s idea of a hot name.

Presumably this why the game isn’t called “Mary Shelley’s Secret Legacy” but employs the more bankable “Frankenstein” instead. Yet I can’t help but think the name “Mother of Frankenstein” is the worst of both worlds, appealing neither to Shelley-heads nor Frankenstein-fans. This baffling decision is compounded by the strange box art and lack of tagline. For the purposes of this newsletter, I could care less whether a game sells a thousand copies or a million, but a book’s cover and a movie’s poster are crucial in setting the right tone and building anticipation.

This is a shame because, with its focus on storytelling, Mother of Frankenstein: Volume 1 is trying something very different to most puzzle games – and it mostly succeeds.