Pentiment

Annoying to play but worth it for the story

PC, Xbox, and Steam Deck

$19.99 on Steam and Xbox, free via Xbox Game Pass

15 hours long

Pentiment is the closest you’ll get to playing Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose – which is to say, investigating a murder in a medieval monastery (hell yeah!). The game is set a few hundred years later than Eco’s book, when the Reformation is about to tear the Catholic Church apart, but it’s just as thoroughly researched.

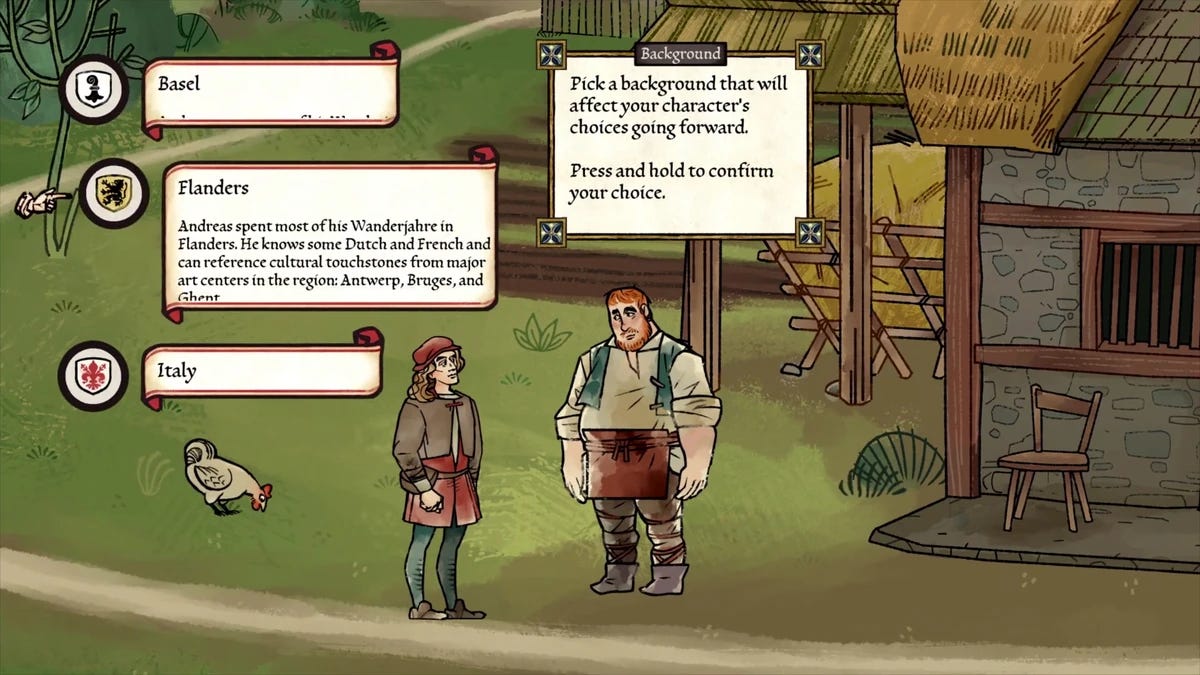

It’s also beautifully illustrated, with the entire game rendered as an illuminated manuscript, with cut-out characters trotting through richly-coloured buildings and gorgeous landscapes. Your character, Andreas Maler, is an artist working at Kiersau Abbey in Bavaria (now Germany), and spending the rest of his time in the nearby town of Tassing. It’s his in-between existence that gives him the unique ability to investigate the murder.

At this point you probably have three questions:

Sounds worthy (games are art, I know!) but is there anything to this other than cool art?

Do I need to like Umberto Eco to get this? Because I don’t know that much about the Reformation.

What is it like to play, and specifically, how boring is it?

To which I can say:

Yes! The writing is excellent and it has things to say about frustrated ambition and the construction of history and the grief of life that goes beyond the usual video game “it’s sad when someone dies” tropes.

Not really. I have read and mostly forgotten The Name of the Rose, and more recently researched medieval pilgrimages and indulgences (which play into Pentiment somewhat), and I still didn’t get most of the historical details until they were explained, which they usually are, and even if they aren’t, it doesn’t matter that much because you’ll figure it out from the context providing you’re not just skipping over all the text.

Now that’s where it gets interesting.

Pentiment is a walking (slowly) and talking (to literally everyone) game. How do you figure out a list of suspects? You talk to people. How do you know who was where and when in the run up to the murder? You talk to people. Talking talking talking. Everyone has a lot to say, not just about the murder, but about their horrible neighbours, or the greedy abbot who’s stopping them from cutting down trees, or the arrogant shithead doctor who’s just moved in.

The good news is that the conversations are clever and funny and memorable, if always a little too long. You can’t say anything wrong in these conversations, let alone “fail” them (the game as a whole is unfailable, which is the way I like it), but your choices can reveal more information or change people’s opinions of you, altering events later on – but again, never putting you in a place where you can’t progress.

Then there’s the walking. Oh the places you will walk! You’ll walk through the abbey’s dormitories. You’ll walk through the forest to gossip with the charcoal burner. You’ll loop around the winding pathways of Tassing, trying to remember which houses you’ve already visited. And every time you move between locations, the game “flips” between pages of a book, which is charming the first time it happens and tedious the next thousand times. It’s not great, and it worsens the malaise whenever you’re at a dead end.

So, it’s not unlike your classic graphical adventure game. There is a slight wrinkle in that there’s usually a ticking clock that gently limits the amount of time you can devote to special activities that reveal more clues (e.g. eating a meal with suspects, helping with chores, going on a hike, etc.); but in practice you have near-unlimited time to scour the town and abbey and run down every conversational avenue with every human for all the non-special-activity-related clues you can get. Which, I think you’ll agree, is quite boring as soon as you start having to backtrack and figure out who it is you haven’t already talked to.

(Not all story-rich games do this! Inkle’s 80 Days and Heaven’s Vault are cleverly designed to eliminate the need for backtracking.)

I suppose the designers might argue your laborious movement around town is meant to make you feel a part of the world, which seems reasonable until you realise Pentiment, like practically all games, plays tricks with space. Sometimes it takes ten seconds to walk past a house, other times it takes ten seconds to walk a mile. This compression of space keeps the game from being even more of a slog. So if you’re already compressing space, why not allow players to compress it even more, with a world map that lets you teleport between locations? We’re already living in a book here!

The tragic thing about this is that it’s all unnecessary. Not just from a game design perspective, in that Pentiment could make it a bit clearer who it’s worth talking to and where it’s worth exploring (the game’s nigh-on unusable “journal” certainly doesn’t help), but from a player’s perspective, in that there’s really very little benefit you gain from doing all this walking and talking.

Because – and this is a slight spoiler, but one in service of getting you to actually play this damn game – you can’t win Pentiment. It might seem like you can ace the investigation just by working and walking harder, but you can’t. The trick of the ticking clock is to make you think that if only you made a different decision you could’ve cracked this case wide open. That makes Pentiment a commentary not only on our futile search for certainty in a world that cannot deliver it; not only a game with characters who are haunted by the belief that they are responsible for every ill they’ve touched; but also an unnecessarily tiresome game to play.

So I am telling you, if you play Pentiment, do not try to talk to everyone. It’s not worth it. You will end up knowing what you need to know anyway. The important things will happen, don’t worry.

There are three more things to mention.

The first is that Andreas isn’t a cipher. He is a person with a history and relationships, some of which you get to define (in a way that matters very little, so don’t sweat it), and some of which you don’t. It’s a little heartbreaking to play as this talented, frustrated, unhappy, well-meaning man who doesn’t quite know what to do with his life. I realise as I write this that Andreas sounds like a bit of an asshole, which is true, but also true of so many young people throughout history, and the game captures that reality and the inevitable shattering of that reality very well.

The second is that while everyone talks about how good the game looks and how each person’s dialogue is animated and rendered in a different font based on their style of speech, which is a cute trick, it’s the writing that’s the real achievement. There are so many words in this game, but very few that are wasted. Pentiment is not just a book-ass game, it’s a grown-up-ass game, in a good way. It will help you see people from the medieval period as people, not as gullible simpletons.

The final thing is that Pentiment has three acts, each lasting about five hours of play. Each act is quite different from the last. If you are getting a little tired of the game, don’t worry – things will change a lot once you sort out your current investigation.

Mild spoilers below!

My spoiler policy: most games take so long to play that we do them a disservice by not talking about everything that happens in them. If I can persuade you to try a game by spoiling parts of it for you, then I will.

Acts 2 and 3 involve major time jumps, which reveal the consequences of the events you’ve just played through. These are not the consequences of your actions – it’s not that dynamic a game, you don’t get to play a completely different act 2 or 3 if you do really well in act 1 – but you get to see how the people of the town and the abbey and their children and grandchildren respond to and remember the things that went down earlier.

It’s not unusual for games to force you into a difficult choice and then ignore it. What’s pleasing about Pentiment is how it embraces this sleight of hand.

It says: your choices are never as important as you think they are.

It says: you are part of a community and you swim in vast tides of events that you cannot possibly change.

It says: you can’t min-max life because you will never have even a fraction of the information you desire.

It says: even so, the little things you say, maybe they will change how people grow up and think about you.

All of this sets Pentiment’s choices apart from many games’ absurd trolley problems where players are presented with literal “save your friend or save humanity” dilemmas, which may be dramatic but are completely overdone.

It’s really those later acts that make Pentiment worth playing, because it’s as much a game about what a community chooses to remember and believe in as it is about solving murders. It’s a game about the construction and telling of history, and how storytelling and, yes, artistry plays into that.

Spoilers over!

Pentiment is the kind of game that gets glowing reviews by English major journalists who adore the fact that they finally get to combine their passions. It is also a game that is quite annoying to play. But you should be assured its annoyances are shortcomings of design, not story.

And while it’s easy to criticise games for their rough edges (believe me, I’m going to do that a lot in this newsletter), what I find exciting about Pentiment is what I find exciting about video games in general: they’re a work in progress. TV is polished to a sheen these days, so easy and satisfying to watch, with the perfect length and perfect technology and storytelling conventions everyone’s grown up with for 30 years. One day games will be like that but until then, we get to live through the time when they’re still annoying to play but weird and surprising and new. Pentiment may be the first ever game that has told this kind of story before. Don’t tell me that’s not exciting!

I want to avoid being an uncritical booster of games in this newsletter. It’s not as if the industry’s survival is reliant on me saying nice things. So believe me when I say that Pentiment is worth playing, if reading lots of text and investigating a medieval murder appeals to you (and if it doesn’t, stay away!).

It is an unusual labour of love, and one that I won’t quickly forget. Just don’t try and talk to everyone!

Have You Played? is an experiment in taking games seriously, but in a fun way. Tell me what you’d like to see more of! And if you liked it, share it with your friends.

I played through this with my 7yo, who is not bothered by a grind, and the pace was perfect to share over a couple of weeks of after-dinner relaxing. Totally agree with your notes.