Roadwarden

It's a hard knock world

PC, Mac, and Steam Deck

$10.99 on Steam

7 to 12 hours long

Roadwarden is an illustrated text-based role-playing game (RPG) where you explore an isolated, godforsaken peninsula in search of the previous roadwarden who’s gone missing, while also trying to re-establish trade and political ties between the peninsula’s fractious settlements and your home city of Hovlavan, while also fulfilling your official roadwarden duties as combination ranger, diplomat, trader, and postal worker. Oh, and you’ve only got forty days.

There’s a lot going on in Roadwarden, maybe a little too much. When you arrive at an outpost on the way into the peninsula (which, I will note, is deliberately unnamed), you meet a couple of guards whom you laboriously ask twenty questions in a row to download into your brain what feels like the entire history and politics and economy and flora and fauna of the region. It’s such an exhausting, un-fun data dump that I almost abandoned the game there and then.

As soon you leave the outpost to explore, the game becomes punishingly hard and obtuse. You start with a handful of coins – but what is a coin worth, and how easy will it be to earn more? How much should I really be paying for dinner? What happens if I choose to sleep in the cheaper stables rather than get a good night’s rest in an expensive inn? You’ll endure too much pain for too long in answering these questions. It turns out that even though you’re an agent of the notional central government here to help the people of the peninsula, no-one gives a shit (probably because the previous roadwarden annoyed everyone and disappeared), and in fact everyone kind of hates you.

This quickly establishes the peninsula as an intriguingly brutal place lacking in trust, but the fact that you’re a homeless civil servant, as one reviewer put it, for the first few hours of the game is a real drag to play. Your chronic exhaustion, filth, hunger, and penury constantly get in the way of doing anything interesting, even just travelling, since you sleep in late if you’re tired. If re-establishing contact were so important to your Hovlavan masters, surely they’d have kitted you out in more than rags given how so many characters judge you based on your clothes.

You eventually learn how to play more effectively: locating cheap places to sleep, securing affordable rations, buying soap so people don’t run away from your stench, that sort of thing. Yet I never felt far enough from utter destitution to pursue interesting and risky quests until I googled “roadwarden tips”, whereupon I learned that a) gambling is such a reliable source of cash that it’s practically cheating and b) fishing traps are the same but with food. I’d never have figured this out on my own, once again demonstrating how forums and wikis make playing games more enjoyable.

Once you have money, you can take on quests that demand more health and equipment, resulting in bigger rewards and new opportunities. This loop allows you to accumulate all the supplies and fancy clothes and armour you could only have dreamt of a mere twenty in-game days ago. Levelling up in Roadwarden is as satisfying and compulsive as in any other RPG, but it’s also faintly ridiculous. The game works hard to establish how tough life is in the peninsula, but how tough is it really when you can go from zero to noble in forty days?

(This is “ludonarrative dissonance”, a term that highlights how weird it is that some games’ narrative portrays the player’s character as virtuous whereas the gameplay – the ludic bit – makes you mercilessly mow down hundreds of enemies. It’s a term that is both an accurate description of a real issue in games but so overused it’s ceased being a helpful criticism; we get it, it’s weird how you kill so many people in The Last of Us! Still, it’s neat to apply it to Roadwarden’s odd power curve.).

If you’ve played Roadwarden, you’re already shouting, “But Adrian, why didn’t you choose an easier difficulty level?!”

True, you can pick between three difficulty levels at the start of the game. The easiest removes the forty day time limit and makes quests easier, while the hardest gives you only thirty days and makes quests tougher.

I dithered for a while before picking the regular difficulty. And I still think that was the right choice. I play action games on easy because, as a child, I was cruelly deprived of a SNES or Megadrive and thus did not hone the fine motor skills required to enjoy such things; but Roadwarden is not an action game, it’s a thinking game, and I like to believe I am just as good at thinking as the average gamer.

Perhaps I’m wrong and that’s why I had such a hard time at the beginning, but a lot of players seem to agree with me, with some suggesting there should be a modified version of regular that keeps the time limit but has easier quests. Maybe! Except I think mucking about with difficulty multipliers (e.g. making food 50% cheaper, combat 20% easier, etc.) only gets you so far and if you want to make a game substantively more enjoyable (which is not the same as easier!), more serious surgery is required.

As for the time limit: while I’m not a fan of artificial timers in games, the standard forty day limit seemed central to Roadwarden’s premise. I liked the idea that whether I did “everything” or not, I’d have had a complete experience as the designer intended.

Which is what I got. Few other games have transported me like Roadwarden did, with its richly detailed world emerging from haunted ruins and broken promises and sideways glances and seemingly mundane quests. Instead of a classic hero arc to save the world, most of my time was taken up by routine roadwarden tasks: clearing roads, repairing bridges for trade caravans, driving out wolves, delivering packages, playing matchmaker, finding someone to read a letter for a farmer. Practically everyone you meet has some grudge, some revealing tale, some little request.

And sometimes those requests are bigger, involving many trips over many days. These can open up new areas for exploration and force you to make tough choices. There are plenty of opportunities to do the right thing or to betray people’s trust, with no traditional “morality meter” tutting at you; usually the only lasting consequence for being selfish is your own guilt. Most people identify Roadwarden’s message as anti-colonialist, which isn’t wrong, but I’d argue it eschews the usual RPG didacticism to ask an even wider question: what is it like to be the person who picks up the pieces after a storm, knowing you may be bringing another on your heels?

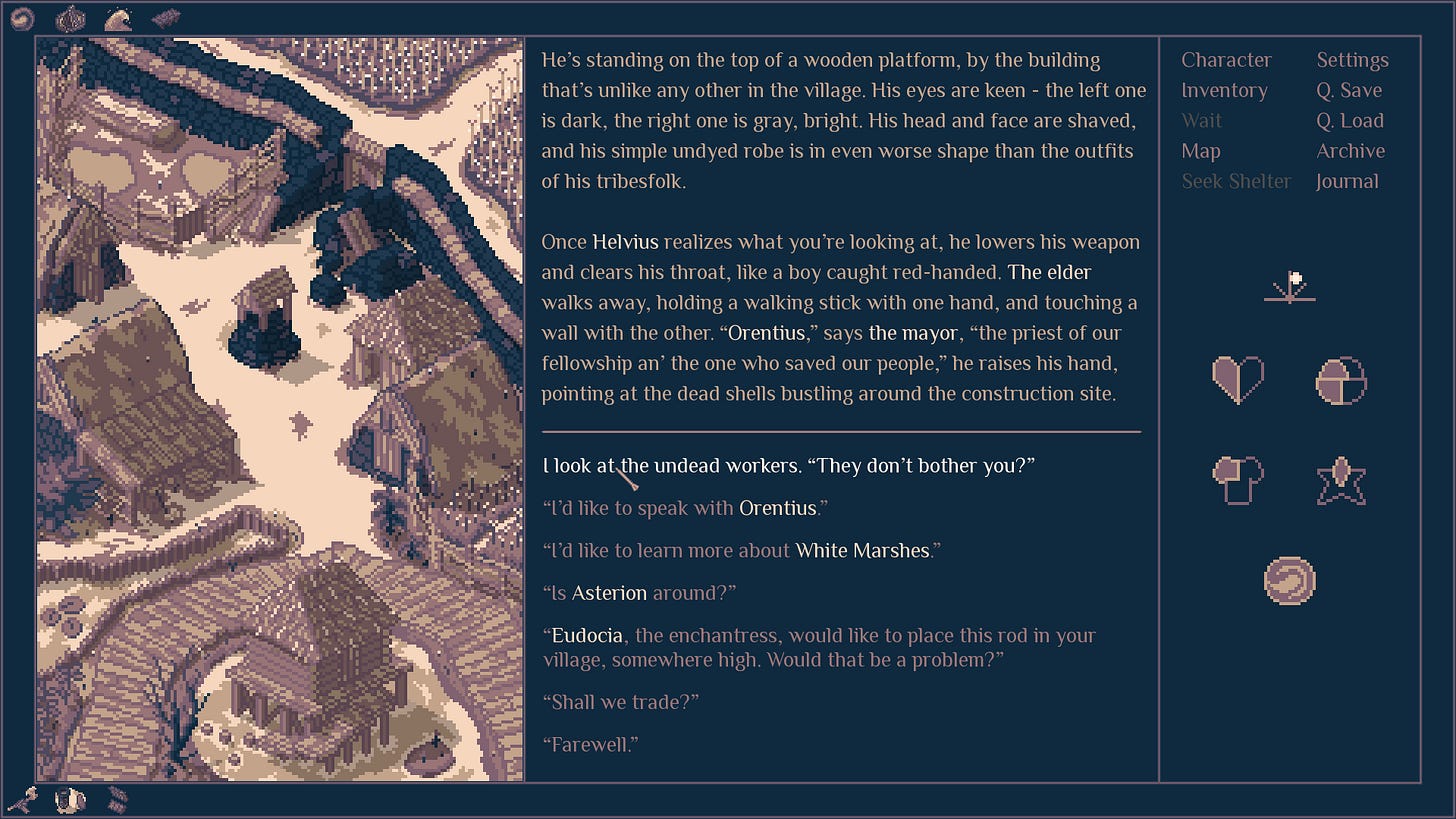

All this amid a world of high fantasy. Cults, guilds, zombies, golems, magic, blood sacrifice – they’re all here, except without the usual kings and castles. Instead, we get a power-hungry, expansionist mayor; a foolish merchant wasting his money on snake oil; a commune of the young who you alternately admire and condescend to.

Each and all are well-drawn despite Roadwarden’s reserved, monochromatic appearance. Artwork is reserved for maps and locations rather than characters, who you only see in big, book-like chunks of text. Sometimes the style makes the peninsula blend together but overall it’s a subtle, effective accompaniment.

Even the place names are evocative. I found myself murmuring the name of my home city over and over again, even when I wasn’t playing. “Hovlavan,” I’d say, savouring its mouthfeel. Gale Rocks. Pelt of the North. Howler’s Dell. As you reach them, you uncover a bit more of the pleasingly non-literal map. Places right next to each other might involve arduous hikes, whereas the long eastern road can be traversed speedily if you’ve cleared it.

The forty day time limit means that even if you’re rich, you still have to worry about whether you’re spending your time efficiently. Travel is counted in hours and it’s dangerous to venture out at night, meaning that as the days grow shorter, the difficulty neatly ratchets up. Unfortunately I wasted a lot of time revisiting locations and talking to people just to see if their quests had advanced; in theory the game’s journal would help with this, but as is the case in so many RPGs… it doesn’t.

Then again, my aimless wandering made the peninsula feel like an open world. When I couldn’t figure out what I was “meant” to do next, I’d trot around setting fish traps, foraging for food, and repairing huts. But the game never quite manages to be a real open world, partly because its systems aren’t flexible or complex enough to support the illusion. There are merchants you can buy and sell things from, but there’s no proper economy of scarcity and abundance. You come across dangerous beasts but it all seems a little random rather than part of a living ecosystem. And so the game’s limited options means you can never ignore its prompts to pursue the main quests.

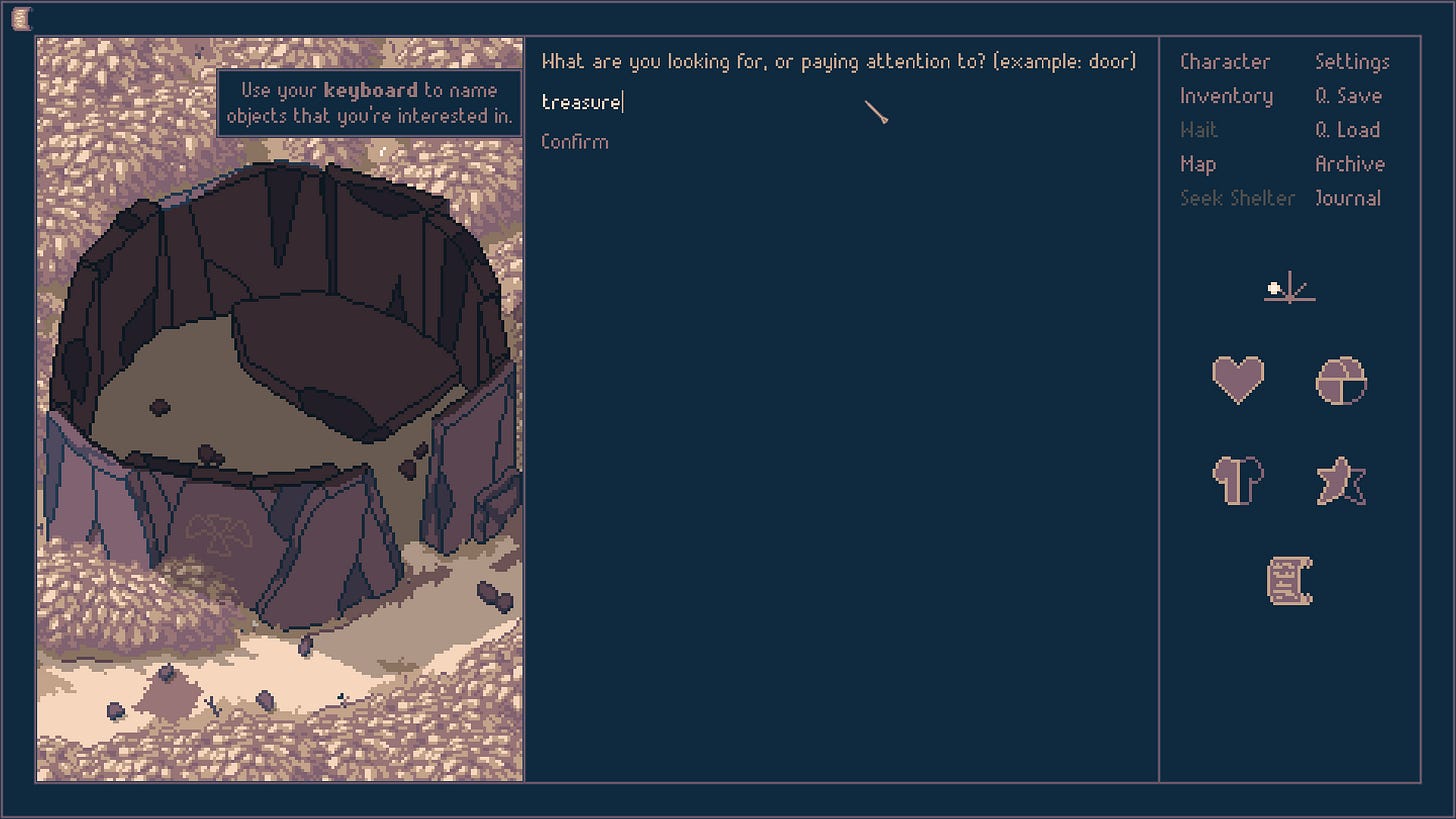

Speaking of prompts, you’re occasionally invited to answer open-ended questions like, “what are you looking for here?” or “who would you like to meet in this town?” This is a very text adventure/interactive fiction thing to do, one that’s been largely abandoned in modern RPGs because, essentially, it asks too much of players who are accustomed to quickly selecting options from a list, as Roadwarden itself normally does. Initially I found this off-putting but after I saw it a couple of times, I opened a notes file on my phone to keep track of interesting names and objects. It was fun to feel like a detective, but the experience wasn’t entirely successful because, like in so many text adventures, it was annoying to have to guess which exact word it wanted me to use. Will ChatGPT rescue this game mechanic? We’ll see…

It took about seven hours for me to complete my regular difficulty run of Roadwarden. Judging by the achievements I unlocked and what I’ve read of the story online, I saw just about half of the story, which means there were entire quests I didn’t begin and whole environments I didn’t see. Like I said, I feel I had a complete experience, but the game is clearly designed to reward multiple playthroughs. I have mixed feelings about this. I’m not a professional reviewer; I don’t have the time to play Roadwarden another two or three rounds, but I worry that I’m shortchanging it because I haven’t seen everything. Then again, we’re overdue a conversation about how games should respect players’ time rather than demanding ever more.

Yet I suspect Roadwarden would’ve been better if it were either:

Bigger, with more open world gameplay inside a properly simulated ecosystem and trade economy, more sophisticated character attributes, etc. OR

Smaller, with more help on finding and completing quests, and less time spent simply trying to feed yourself and make money.

The game’s extreme difficulty at the start is a consequence of a highly compressed power curve playing out within a relentlessly hardscrabble world. If you went bigger, you could extend the time limit and smooth out the curve. And if you went smaller, you’d have no power curve at all, focusing more on the great story and characters.

I find it hard to criticise it for landing in the middle. Roadwarden was apparently designed, written, programmed, and illustrated by a single person – an astonishing achievement and a recipe for unconventional design decisions. But it’s a shame the game isn’t a touch more approachable. Holding people’s hand isn’t so bad. That’s how you pull them into your world – and Roadwarden has a hell of a world.

Follow-up

A reader suggests Season’s overwrought writing (covered last week) is because it was originally written in French and then translated directly into English. “I can also say it's very, very common to hear this kind of really cerebral language in French. not so much in English, right? but the French really don't seem to give a shit. 😄” The studio behind Season is based in Montreal, so perhaps…

Links

‘OOTP Baseball:’ How a German programmer created the deepest baseball sim ever made (The Athletic)

Organised fun: who’s it all for? (The Face)

Can Pachinko be Skill-based? Taking a look at Hanemono (nicole.express)

A game I've played! I picked it up after watching a Twitch streamer play (vicorva). I really enjoyed it as a read-aloud game, although as a choose-your-own adventure game, I wanted more options and more paths to explore rather than ending up at mostly the same thing on subsequent playthroughs.

This looks very cool despite, putting it in my wishlist. The comment about Seasons also has maybe solved a very minor puzzle for me, which is why the text of Iris and the Giant is so terrible while everything else about the game is very good-to-excellent.