PC, Xbox, PlayStation, Switch, and Steam Deck

$19.99 on Steam, free on Xbox Game Pass

9-10 hours long

Signalis is a retro-styled survival horror game, played mostly from a top-down perspective, where you explore an abandoned government facility on another planet. As you piece together a mystery, you descend lower and lower into the facility, solving puzzles and evading or killing strange creatures as you go.

I’ll be upfront: I didn’t finish Signalis. I stopped two hours in, when I wasn’t enjoying it any more and had seen enough to have something interesting to write about. From what I’ve read, I got a quarter of the way through the game and saw a decent cross-section of the gameplay, but if you’d rather hear about the game from someone who’s finished it, I wouldn’t blame you.

So what happened? The truth is that I didn’t realise it was a survival horror game. I got it for free via my BAFTA membership, so it’s not like I mindlessly bought this game without reading its description; it’s more that I mindlessly downloaded and played it. I’m certainly not blaming the game’s developers for this, who literally starts the description with the words “a classic survival horror experience”.

But why did I choose to play it out of all the games I could play? I liked the way its moody tableaus looked in screenshots, only one claustrophobic room showing at a time. It looked confident and different. The problem is that you can’t guess gameplay from a screenshot.

You wake up in a spaceship that’s crash-landed. Who are you? Pamphlets scattered around the spaceship explain that you’re a humanoid service robot. What’s the setting? Other conveniently-scattered pamphlets allude to your “great nation” being at war with some enemy. What’s the purpose of the mysterious facility near your ship? Pamphlets, posters, memos, all the rest.

I generally enjoy epistolary storytelling and “found materials” like posters and emails, and I didn’t think Signalis’ were particularly good or bad. The problem is that they don’t work well with Signalis’ pixellated top-down perspective. When you’re playing a game with a 2D side-on perspective, you can see a poster on a wall and get its gist, even if you have to zoom in to read it; and if you’re moving through a 3D world, it’s even easier to move from noticing to reading. But in Signalis, it’s a chore to walk over to every pixellated pamphlet-shaped object in a room to see if it is, in fact, a pamphlet, then press a button to read it. If you only had to do this occasionally, fine – but it happens so many times and the writing isn’t so good that it’s worth it. And don’t think you can skip this homework, either. Solving the puzzles that allow you to explore the facility means collecting and reading everything in sight. More on this later.

The puzzles are pretty good, to be fair – reading the pattern on an ID card in a photo and inputting it into a computer, unlocking a door with a dead guard’s key – but some use absurd conventions I wish games would abandon, like a memo complaining about a security code being broadcast repeatedly on the radio, so of course you need to find a radio, tune it to the right frequency, then find the safe to type the code into. Does this make any sense whatsoever? No.

Not that everything needs to make sense in a game so long as you’re getting something else out of it. Every so often, Signalis smash cuts from its top down perspective to a first person view where you’re climbing down a blood red tunnel or stumbling through a snowstorm, then smash cutting again to a screen with unsettling text and creepy classical music. These flashes of surreal brilliance prevent the game from becoming completely pedestrian and reminded me of Thirty Flights of Loving’s stylishly disjointed storytelling, which remain the best use of smash cuts in games I’ve seen.

I hungrily anticipated these first person moments, which were also used for the more interesting puzzles like a cutting a computerised lockpick or operating a 3D scanner. Unfortunately, most of Signalis is something very different: combat and endless backtracking.

First, the combat. The facility contains zombie-like creatures that can be killed with guns or tasers or flamethrowers, or if you’re careful, evaded. Nothing special about that, but the “survival” part of “survival horror” comes into play because Signalis offers:

Limited ammunition

Limited carry capacity (you can only carry six items at a time, including weapons, health items, keycards, etc.)

“Permadeath” with limited save slots (if you die, you can only restore to one of four save slots, and you lose all progress made beyond that point)

Killed creatures unpredictably reviving themselves

Slow movement and unusual aiming controls

This makes Signalis harder than games with plentiful ammo where you can run in guns blazing, or games with quicksave or autosave, where if you die, you can immediately try again having lost only minute of your time, or games with movement controls that more players will be familiar with, or… the point is that while I didn’t find it unfeasibly hard, it’s very deliberately on the tougher end of the spectrum.

(As for the “horror”? The creatures are a bit scary, but no more than most zombies. The fixed top-down perspective does make it hard to see if they’re lurking in shadows, which is neat.)

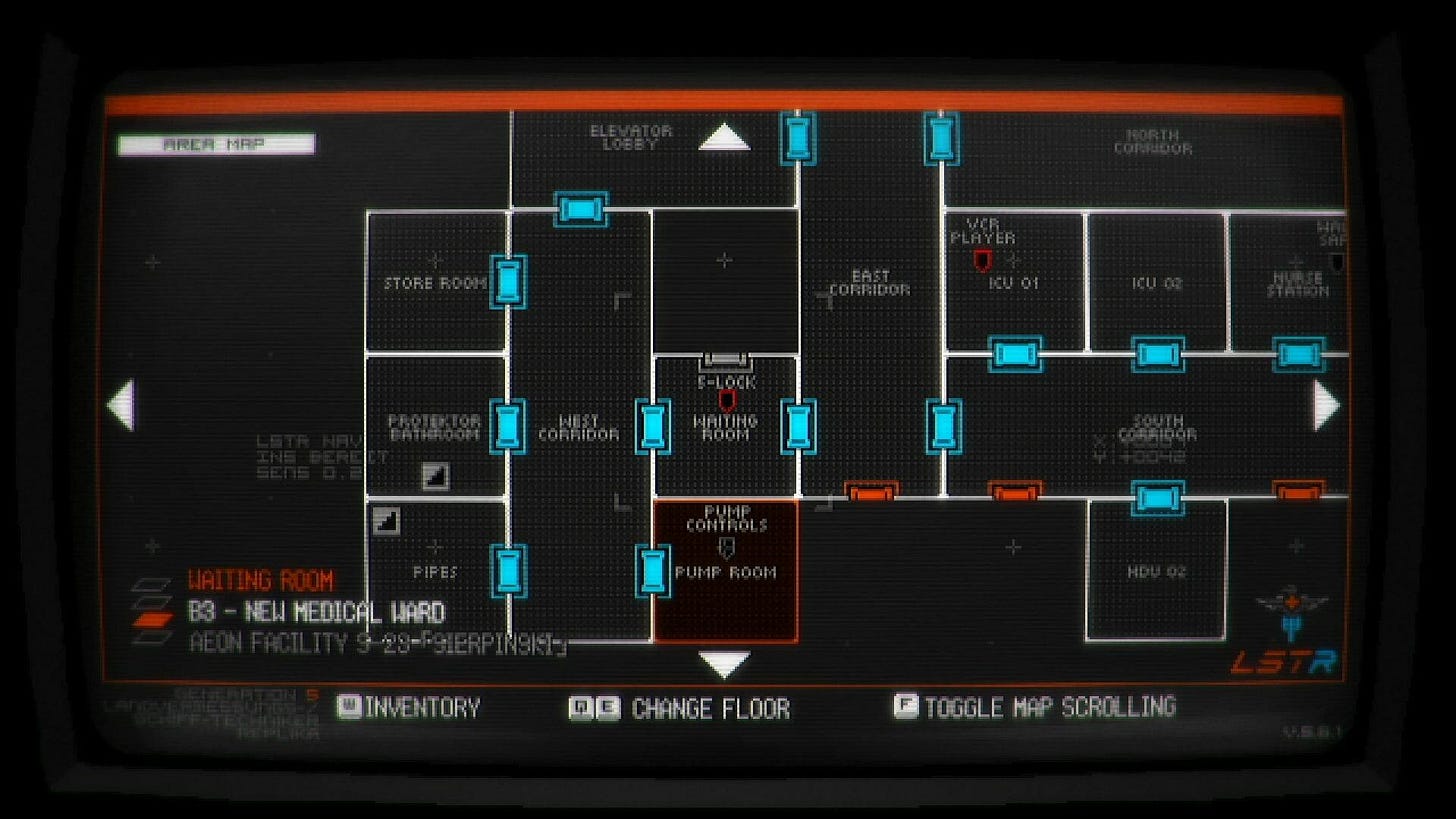

Now for the backtracking. Most levels of the facility have dozens of rooms and corridors. Solving puzzles and unlocking doors to new areas involves lots of walking back and forth to collect a key, unlock a safe, bring the widget from the safe to the computer, find another widget, bring it to the computer, use the computer to unlock a lift to the next level, and so on. This kind of gameplay is termed Metroidvania, after Metroid and Castlevania, two games from the 80s that involved a lot backtracking to unlock new areas and abilities.

If this sounds dangerously boring, you’re not alone. Not long into the game, I got stuck. I’d collected every item and opened every door I could, but there wasn’t anywhere else to go. On consulting a walkthrough, I discovered I’d missed a safe in a nurse’s station. I was sure I’d searched every inch of it, but it was true, there was a blob of safe-shaped pixels I hadn’t walked next to. A little after that, I got stuck again, and discovered I’d failed to pick up a key that had been lying in a puddle on a bathroom. Cue more trekking back and forth to get these necessary items to progress, during which I was liable to get jumped by creatures at any moment. There was no journal to allude to my mistake, no character hinting to look in the bathroom, no map indicating I hadn’t explored a room properly, not even a hint from my own character’s voice, despite the fact that they occasionally commented on other events.

And so I stopped playing. I hated the idea that if I missed just a single thing, I might get stuck and spend ages combing through every single room.

Since I didn’t come close to finishing it, I won’t spend a lot of time on Signalis’ story except that I found it too slow and cold and derivative. Yes, I’m aware it’s doing Ghost in the Shell, it’s doing Lovecraft (you literally come across a copy of The Yellow King early on), but references alone don’t make for a good story. Do I just have to drop in a copy of Macbeth in my game to make it deep? It’s all very 80s sci-fi: words like “rationmarks” and “protektor” are mixed with Asian glyphs, unreliable memories, and a pinch of Lovecraftian horror. It didn’t hold my interest.

Signalis follows design conventions from much older games like Metroid and Resident Evil and Metal Gear Solid, like no hints and limited carry slots and backtracking and permadeath. Why are they conventions? Because those games are beloved and people are inspired by them. But are these particular conventions brilliant, timeless principles of game design, or are they accidents of history due to limitations of resources and technology?

I’m struggling to imagine how it’s desirable for a player to be stuck for hours because they didn’t notice a blob of inconspicuous pixels. I’ve played plenty of games where I’ve put up with it, backtracking to every room or location in search of what I’d missed. Sometimes the movement and combat were so pleasing it didn’t feel like wasted time. Sometimes the dialogue or environment changed while I was backtracking so I didn’t get too bored (but then it’s not really backtracking, is it?). Sometimes backtracking was sped-up through teleportation (ditto). And sometimes the rest of the game was so good, or the alternatives so bad, the tedium was worth it. But it’s never been desirable.

These days, most games have systems that prevent or alleviate backtracking. Signalis’ lack of them is either deliberate or via neglect. If it’s the former – in other words, it’s designed to be far more unforgiving than contemporary games – it’s not clear why they included difficulty settings that make combat slightly easier, but not anything else. Signalis’ use of multiple perspectives and smash cuts shows they’re willing to break convention, so why not also add options like a journal, unlimited carry capacity, aim-assist, indicators for interactable objects, maps that show rooms that haven’t been fully explored, and so on? My guess is that it’s more acceptable, or at least more necessary, for designers to polish a game’s appearance than to make it better to play. Consumers – like me! – can see a changed appearance in screenshots and trailers, but they can’t see changed gameplay.

So then there’s neglect. And this makes sense to me given how Signalis has good reviews all round. Perhaps it’s so well-targeted toward survival horror enthusiasts that everyone who plays it likes and demands extremely hard games and is used to the genre’s odd conventions, and anyone who doesn’t is scared away by its genre, a bit like how people who hate horror movies aren’t going to stumble into the Evil Dead by mistake – unless you’re as foolish as me.

But I think there’s a difference. I don’t like gore or jump scares, but I love the inventiveness of horror movies like Host and Barbarian and Nope, and all I have to do to get the good stuff is occasionally close my eyes. I love the inventiveness of Signalis too, in its presentation if not its story, but there’s no way for me to skip what I consider to be tedium and excessive difficulty. It’s as if, in order to watch Train to Busan, I was quizzed every ten minutes on everyone’s names and the circumstances of every zombie kill and gory death. No doubt some people would like that! And if this test-enhanced Train to Busan were profitable, maybe its filmmakers wouldn’t feel the pressure to change anything, especially if they and all their fans had grown up watching other films that made them pass tests.

Signalis aside, we’re seeing a long-overdue reassessment of how hard games should be, no doubt out to a desire to make more money from less-skilled players, but I’m sure also because game creators, having devoted so much time and energy and sweat, would like more people to appreciate their art. So now we have games like Celeste and Hades adding lots of difficulty settings and modifiers that allow unco-ordinated people like me to enjoy them, while still being brutally hard for those who like that kind of thing. Even Nintendo has added affordances like suspend points and the ability to rewind time in their retro games.

What excites me about games is their untold variety. What worries me is that variety turning into a thousand niches, each laser-targeted at those who’ve already invested ten thousand hours into becoming experts, and each completely inaccessible to those who haven’t.

Difficulty isn’t always a virtue, and conventions aren’t always worth maintaining.