Squid Game Immersive Gamebox

It turns out the least interesting thing about Squid Game is the games

£26 per player ($33; 2-6 players)

60 minutes long

In a venue dedicated to “competitive socialising” the Squid Game Immersive Gamebox might be a little too on the nose. Based on the hit South Korean TV drama where 456 contestants compete to the death across six children’s games, this experience sees players work together in the same six games to earn points.

It may be predictable Netflix would transform a satire of capitalism and reality TV into a real reality TV show and immersive experience, but that doesn’t make it any less horrible. These rancid vibes are mostly, but not completely, sanitised by Immersive Gamebox’s version, whose unusual motion-tracking technology cannot save the fact that:

Games designed for specific physical contexts (e.g. big playgrounds) require a lot of work to be fun elsewhere

There’s a reason children’s games are for children, not adults

The least interesting thing about Squid Game is the games

But what are such concerns against the profit to be made adapting their biggest show of all time to every platform imaginable?

An “Immersive Gamebox” is a room where three walls display images from ceiling-mounted short throw projectors. Each player wears a hat whose position is tracked very reliably across the room, though crouching or jumping makes no difference to the game because it can’t sense depth. Our attendant told us to imagine our hats as controllers in a video game, which was a good analogy. The walls can detect touches, but only crudely – you need to place your entire palm against the wall and even then it doesn’t always work. There’s certainly no Kinect-style depth or silhouette tracking, let alone skeletal mapping.

This meant the floor had to be completely clear so no-one tripped over bags, and any bags and drinks had to be at the back rather than resting against walls where they might trip off the “touch sensors” (in reality, cameras looking at the walls).

1. Red Light, Green Light

After a brief intro video, the game begins with Red Light, Green Light. One player at a time moves from the back of the room to the front via a series of circles, freezing when the giant girl’s head turns to face them. The player is shown by a coloured dot on the front wall: if they walk forward, it moves up the wall; if they walk right, it moves right. This makes the front wall a top-down projection of players’ location within the room’s floor, an interface re-used in most of the six games.

Because it’s your hat that’s tracked, it’s possible to freeze your entire body but still get caught if your head wobbles only a little bit. This happened several times in a row, which was an awful start; the designers should’ve turned down the sensitivity for the first few rounds to ease players in.

Another problem: The girl’s head turned far too often. This is because the room is much smaller than the playground-sized area this game is usually played in, meaning you need players to freeze more frequently otherwise it’s too easy. Understandable – but not fun, given that it was so predictable. I suspect the designers also tuned the game so players would get eliminated as quickly as possible so the next person could have a go.

A bit of variety was introduced by deadly spiky walls to navigate around, then with rounds where two players moved at the same time. Each player was kept to their own half of the room, which was probably for the best. The winning strategy was always the same: making a dash directly to the next circle if it was close enough, or just leaping halfway and then freezing.

Each round had a timer of around 30 seconds to prevent the player from being too cautious, and the entire game had an overall timer of about 7 minutes. Scoring felt more or less meaningless but was based on the number of times a player reached the front of the room safely and the number of times someone was caught out (“eliminated”). Eliminations were counted by the 456 fictional contestants being whittled down, so if you got caught ten times, you’d end the round with 446 left – except in this game they weren’t machine-gunned to bits like in the show.

2. Dalgona

In Dalgona, players trim the outline of a shape from a piece of sugar candy by walking a set path. Deviate from the path too much or take too long and you’re eliminated. As rounds progress, shapes become more complex (e.g. triangle > circle > umbrella).

It’s easy to understand, at least – onlookers were cheering and groaning as we played – but I found it more uncomfortable than fun. Maintaining the accuracy required wasn’t easy, necessitating a fast shuffle around the room. I was glad to see the back of this one.

3. Tug of War

Tug of War is a rhythm game where players move onto circles in time with a musical beat. Successful moves means your team pulls an opposing “enemy” team toward them, and if you do this enough times in a round they fall off the end of their platform.

This was fun thanks to all the things that make games like Dance Dance Revolution fun – the pleasure of moving your body in time with music. It was also more social because there were always multiple people playing at once. It didn’t get perceptibly harder over time, but the game was short enough to remain fun.

For some reason, the designers chose to depict the enemy team plummeting into space when you win a round. This isn’t anywhere near as graphic as the show, where you see them fall to their deaths dozens of metres below, but it’s the most the game reminds you that hundreds of people die in the original story. Fun!

4. Marbles

One player at a time rolls marbles into a field in order to push “enemy” marbles out of it. Players choose a marble (small, medium, big) by touching it on the wall, then walk around the room to aim it. Each marble has a point value; if the total score of your team’s marbles in the field exceeds that of the enemy’s, you win the round. Later rounds add more enemy marbles.

This may have been the most boring game because it was so easy. The only challenge came from trying to maintain the correct aim while touching the wall to “fire” a marble, yet another limitation of the motion-tracking technology.

5. Glass Bridge

Glass Bridge is a memory game where players work together to memorise symbols displayed on the right and left walls.

For example, if the left wall displays a lion, wolf, and eagle, and the right wall displays a lion, wolf, and tiger, the question “Which side had the bird?” is correctly answered by players moving to the left side of the room. If a majority of players make the correct choice, the team moves forward along the bridge. If they choose wrongly, something bad happens, but I’m not sure what because my team was just too good.

It’s fine! There’s a mild thrill in shouting out what symbols are on each side, but it never got difficult even as the number of symbols increased. It’s notable this is very different to the show, where the glass bridge involved zero skill at all. Instead, contestants jumped forward onto the left or right glass slats of the bridge and died or survived at random.

6. Squid Game

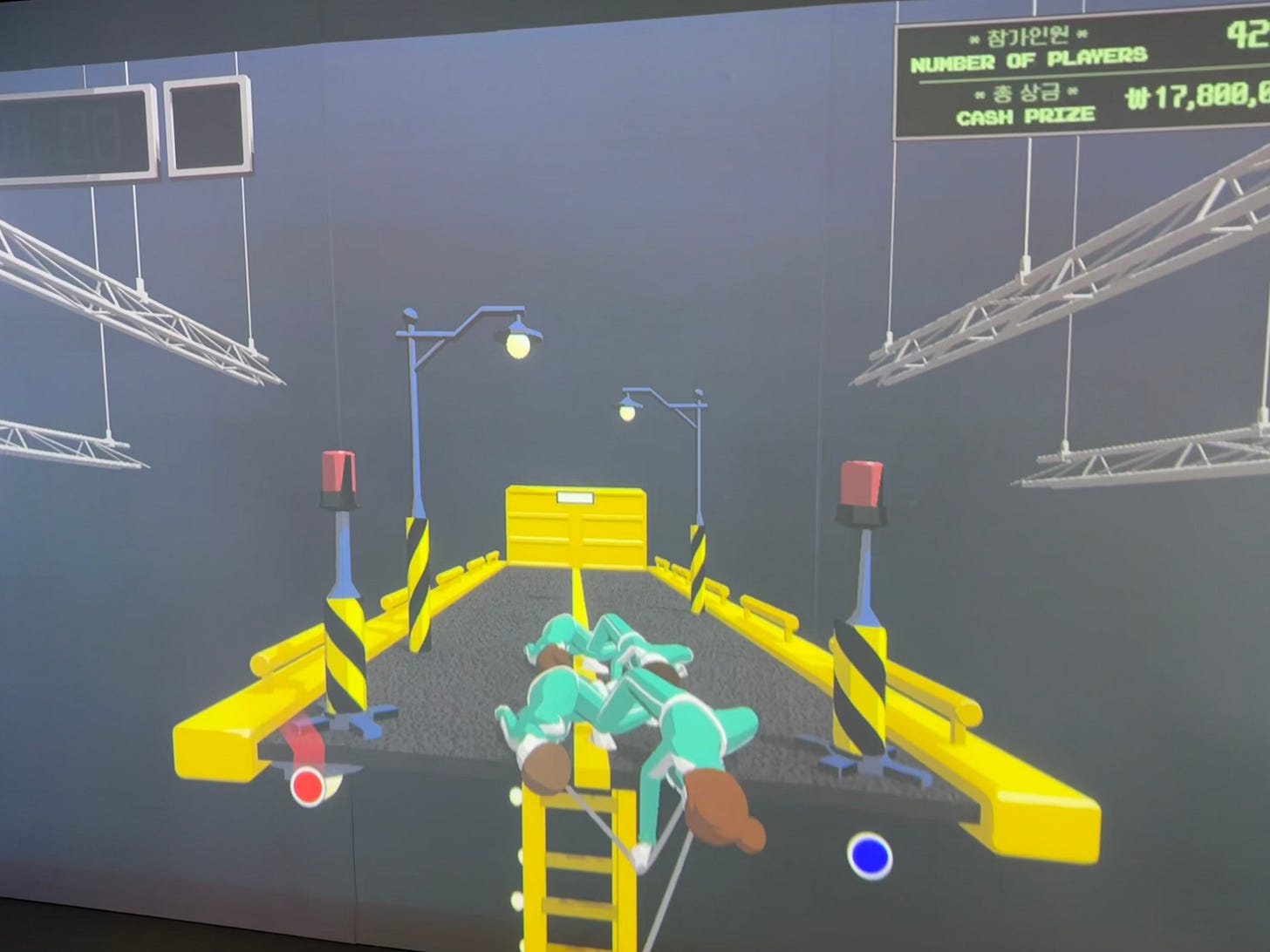

One player at a time avoids walls and dodges enemies on their way to a “home” area. The difficulty ramps up as enemy number, speed, and detection distance increases. By later rounds, players have to strategically lead enemies away in order to reach home.

The enemies’ rudimentary AI makes this the most video game-y of all six, which is mostly a good thing since it rewards skill and is exciting to watch. However, since the walls and enemies are, as ever, projected on the wall, it involves a bit more abstraction of movement than some players might enjoy.

Scoring

Your team’s score is totted up based on their performance in the six games plus the total number of remaining contestants, where it goes onto a local and world leaderboard (there are also scores for individual players). The room takes a short celebratory video of your team; while it’s being “processed”, a trailer for another game plays – in our case, Ghostbusters.

All in all, the experience took about 45 minutes – a bit shorter than the hour promised, but then again, we were only two players.

From a business and technical perspective, the Squid Game Immersive Gamebox is quite interesting. It uses surprisingly dated motion-tracking technology when an Xbox Kinect-style solution would have allowed for a broader range of interaction – players could have synchronised pulling a virtual rope with their hands in Tug of War, and Red Light, Green Light could have featured a side-on instead of top-down perspective, better for hiding behind obstacles.

Yet most people seemed to be enjoying themselves! I can’t deny that Immersive Gamebox experiences are novel, unlike bowling and karaoke, and more accessible than most boardgames and card games, which require more setup and explanation. If you’re a family desperate for anything to do that isn’t watching TV on a weekend, it’s an intriguing if pricy choice (£26/$33 per person, remember!). The best comparison in terms of price and duration are escape rooms. Since Immersive Gamebox rooms are so small and have fewer things to break, however, they can fit inside venues with more footfall like arcades and cinemas, and only require one supervisor for a set of rooms. They also have slicker IP-based marketing (Squid Game! Ghostbusters!) and promise a less stressful experience than many people’s associations with escape rooms.

As far as their Squid Game experience goes, however, that accessibility conceals a lack of depth and character. The things that make escape rooms more varied and occasionally frustrating are what gives them imaginative puzzles and joyous moments of discovery. Still, if you want entertainment that passes the time but is entirely forgettable, you could do much worse.

In the final episode of Squid Game, the mastermind reveals he chose the six games because he enjoyed them as a child. This explanation is incomplete at best, as we’re also told the “Squid Game” was invented to entertain psychopath billionaires, as a kind of snuff reality TV. Children’s games work because it’s easy to tell who’s winning or losing, unlike chess or Go.

It’s humiliating to be forced to play any game, but doubly so when they’re games made for children, which in their execution in the show end up being as much about luck as skill. Some contestants in Dalgona only have to cut a circle out of their candy, while others contend with a near-impossible umbrella. That’s not fair, but the billionaires enjoy watching them fail: here, the cruelty really is the point.

The drama in Squid Game isn’t about the games themselves. They’re too simple and boring! There’s only so much mileage you can get out of marbles or a tug of war. In video game terms, they’re minigames like lock picking or wiring circuits, ways to fill time rather than the main attraction. The drama is about how the contestants save and betray each other, the ways they cheat and bargain for advantage, and their tragic reasons for joining in the first place.

A game that embraced the true horror of Squid Game would force players into the same dilemmas. Now that would be memorable.