PC, Xbox, Playstation

$39.99

11 hours long

Star Trek: Resurgence is a dialogue-driven adventure game where you try to prevent an interplanetary war. You play as two characters on the science vessel USS Resolute: Commander Jara Rydek, the incoming First Officer, and Petty Officer Carter Diaz, an engineer.

A lot of your time is spent talking, where you choose dialogue options that will change the crew’s opinion of you, with potential consequences later on. Occasionally you walk around and explore small environments, but otherwise your interactions are “on rails” and confined to, say, pushing a button to turn a lever or flying a shuttlecraft from A to B around some asteroids.

This game is very consciously designed like an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG), right from the chapter titles, which confusingly appear every 5-15 minutes, to the conveniently identikit Starfleet uniforms. It’s written like TNG, too: you’re helping Ambassador Spock mediate between two planets on the brink of war. Very 90s-style post-Cold War US diplomacy! This mission is complicated by a classic TNG workplace story, where the incoming Commander Rydek must navigate acrimony among the USS Resolute’s senior staff – acrimony that led to the accident that killed the previous First Officer.

So much of TNG’s drama comes from Starfleet being an ultra-hierarchical, quasi-military organisation that exists within a near-utopian post-scarcity society. The “upper vs. lower decks” and “chain of command” tension only works if everyone believes starships must be run as a benevolent dictatorship; in reality, 18th century pirate ships were much more democratic. Then again, it makes sense that people in a post-scarcity society would value status more than anything as silly as material weath, which explains why the USS Resolute’s Captain (whom I call “Captain Hardass”) is so concerned about repairing his reputation and avoiding disgrace, leading to all sorts of interesting conflicts.

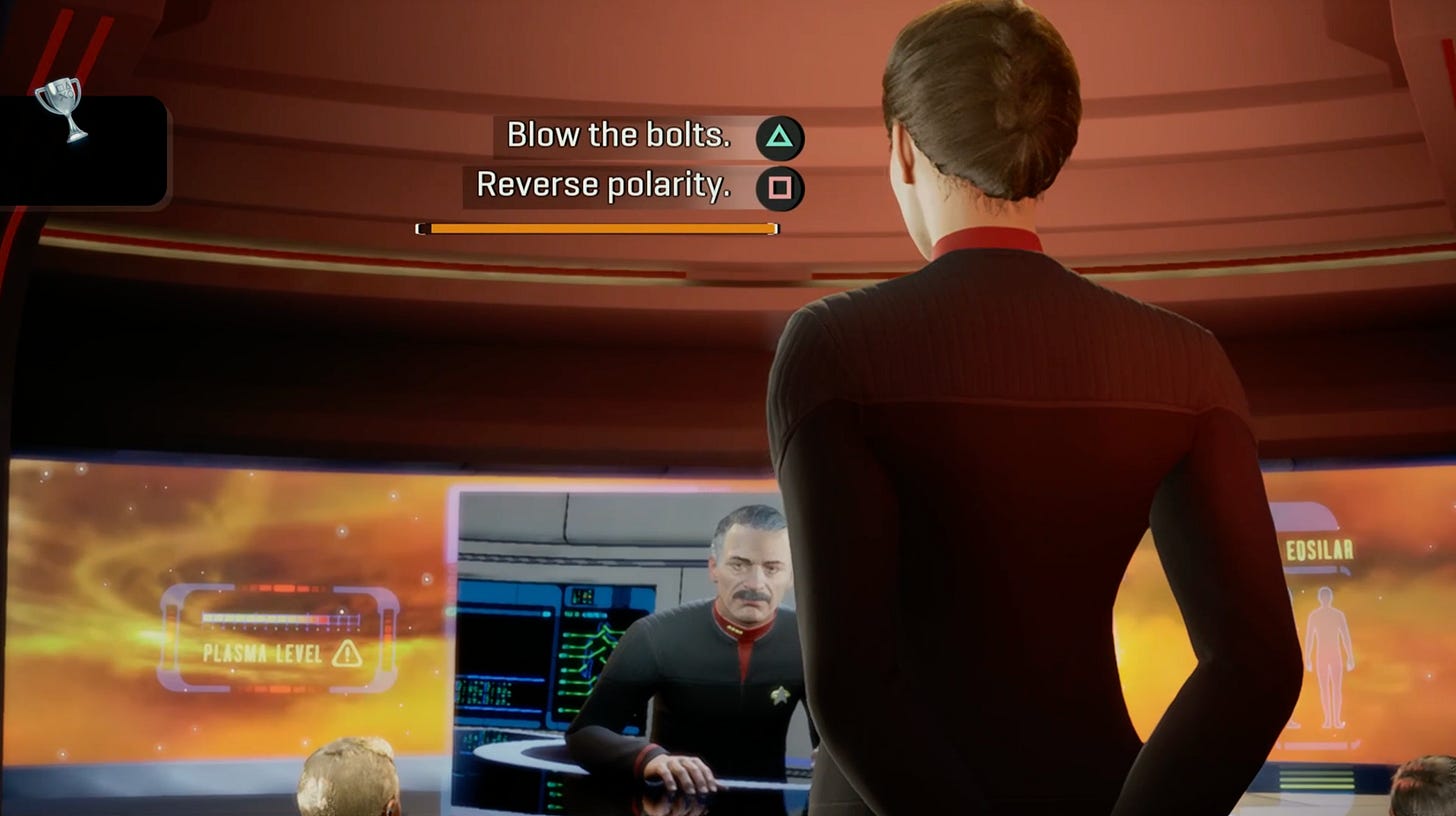

You get to participate in this drama by choosing one of three dialogue options during conversations; these options boil down to friendly, serious, and unfriendly. For example, the medical officer might suggest the Captain is being an unpleasant hardass, and as the First Officer, you can be friendly and agree; diplomatic and say you can’t comment; or tell her off. You only have a few seconds to choose, which keeps things pacy and prevents you from overthinking or over-regretting. The trick isn’t in finding the “right” answer, because it doesn’t exist, but in being consistent and not confusing people by running hot and cold all the time. Essentially, Star Trek: Resurgence is a role-playing game minus the experience points.

Not all dialogue choices affect people’s opinion of you, but when they do, a box will appear in the corner of screen in red, white, or green, corresponding to their opinion falling, staying neutral, or rising. This is not a score! You will find some people annoying and you want them to be annoyed. Pleasingly, you can pull up a menu to see characters’ opinions explained in detail:

It’s unlikely these opinions have major consequences on what you get to do. Practically speaking, creators cannot write quality dialogue if it branches endlessly based on every past choice, and they certainly won’t “gate” puzzles or environments or gameplay based on choices; those things are expensive to make and ideally you want all players to enjoy them. But since the choices feel as if they’re consequential – a character sharply reminding you of something you said a couple of hours ago – it works. Many games try this, but few do it as convincingly and enjoyably as this game.

In fact, it all works. Characters are well-defined, with clear motivations and voices. Dialogue is well-written, if consistently too long. The actors are great and well-directed. The only false notes were the Spock sound-a-like, who wasn’t terrible but sounded like he had a mouth full of wool, and the technical jargon. I occasionally found it so confusing I made a different choice to the one I wanted; and the rest of the time, the talk of subspace variations, warp field calculations, and graviton waves felt boring and meaningless.

If Star Trek: Resurgence focused mainly on its story and dialogue, like its spiritual choice-based, dialogue-heavy predecessors The Walking Dead and The Wolf Among Us, it’d be a much shorter and better game. I regret to inform you that it does not. Instead, it’s festooned with endless little interactions and minigames that, I assume, are meant to immerse you into the role of being a First Officer and Engineer, but instead feel unnecessary at best and infuriating at worst.

Petty Officer Diaz gets the worst of it. As an engineer, you get to open panels (push down on your left stick); rotate levers (rotate right stick), remove computer chips (pull down on right stick and push right trigger), inserts different chips, rotate more levers, etc. Sometimes you get to plot a line through a chart to use a transporter, or slowly fly a shuttle around some asteroids for a few minutes, but none of it is compelling.

At least it makes sense Diaz is doing all this mechanical stuff; Commander Rydek’s interactions are frequently absurd. At one point, I had to spin my left stick to “filter out” asteroids from a hologram to locate a missing ship. Later on, I plotted an intercept course, not by drawing a line as I did for the transporter, but by pushing my stick sideways for a curve to get drawn automatically. I was never confused about what to do, but the level of abstraction was so inconsistent that I was thrown out of the fiction.

Most interactions were so meaningless and so devoid of skill and choice, I’d have preferred it if they were replaced by cutscenes. One sadly memorable exception was when I could choose the order in which I learned about four things from a holo-menu, which I got unaccountably excited by. Another was being able to explore the engineering bay and an alien palace, and inspect things and talk to people at will. But I might trade those moments and more besides if I could lose the game’s tricorder entirely.

The tricorder is a handheld device that can scan inside things. When you’re using it, you peer through a small dark screen and press a trigger when you see an especially bright object. Sometimes you need to switch between three scanning modes which, as far as I can tell, differ only in colour; and scan three objects rather than just one. This sounds simple, and it is, but it’s not so simple that you can do it quickly because pointing the tricorder is slow and cumbersome, and the bright object you’re looking for is often hidden in a group of other bright abstract shapes.

You will scan parts of a shuttlecraft. You will scan equipment panels. You will scan bodies. You will scan plates of food. None of it is any good. I am especially biased against the tricorder because a bug made me repeat a level three times because I was scanning things too quickly (lol); and a dreadful puzzle made me scour a room for a near-invisible object.

A few hours in, you explore an alien moon and have to retrieve a keycard without being seen by patrolling guards. As is typical in stealth gameplay, you need to watch them, learn their routes, and time your movements accordingly. Supposedly the game would warn me if guards were alerted to my presence, but in practice if I ventured somewhat near one, I would be instantly killed. After a couple of tries where I couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong, I enabled “Story Mode”, whose function was not clear but I think allowed me to skip ahead to the subsequent checkpoints in the stealth section if I died. This was better than the game forcing me to do the stealth properly, but worse than not doing it at all.

Many people hate stealth missions in action adventure games like Assassin’s Creed or The Last of Us because unlike parkouring or shooting zombies, which their creators spent a lot of effort in getting right, stealth was an afterthought. Perhaps stealth is unusually challenging to design well because failure is made to be so punishing (instant death and/or replaying the level) and consequently the learning loop is so long; but there is nothing inherent about stealth that makes it bad. I like stealth-centric games like Metal Gear Solid V and Hitman because they implement ideas like vision cones and alertness meters and tagging of enemies and generous difficulty modes that other games don’t. The point is: don’t do stealth unless you absolutely have to and you can do it well.

But there is no good reason for Star Trek: Resurgence to include stealth, any more than it has to to include phaser shooting (equally bad) or tricorder scanning (awful) or the hundred pointless little interactions you do along the way, except to give you something to do other than make dialogue choices, as if the creators were somehow embarrassed by having that as the core gameplay. Either that or they added stealth and tricorders because they thought they’d sell more copies that way.

It is true that TNG episodes involve tricorders and transporting things and flying shuttles and sneaking around guards, but that doesn’t mean a TNG-style game is obliged to turn those things into gameplay. The cliche about TNG is that it’s a TV show about meetings in conference rooms, which is both funny but also what makes it unique. So if you’re going to make a game about TNG, throw all your effort into what makes it unique (dialogue choices) and skip everything else, just as shooting games throw all their effort into making shooting feel good and turn all the story into cutscenes.

Perhaps if Star Trek: Resurgence dropped almost everything other than walking and talking, it could’ve improved its graphics. The game’s 3D art style aims for realism, unlike the cartoon-like cel shading of The Walking Dead, but falls far short. When you’re walking around, the environment and characters look worse than games from twenty years ago, with poor lighting (e.g. very shiny hair), basic shapes, unrealistic animations, and primitive shaders. Characters share near-identical models (everyone is very slender) and poses and uniforms. It is distractingly bad. Even when sneaking into an alien outpost, Commander Rydek doesn’t bother changing her uniform; where’s my classic TNG hooded cloak disguise?

At least the aliens look better, as they often do in video games; they’re designed on the right side of the uncanny valley, unlike the humans. Certain cutscenes and conversations also look good, with improved lighting, facial detail, depth of field, and cinematography. These moments are well-edited; I particularly liked the classic “departing starbase” sequence. Some very talented artists worked on this game.

Unfortunately, the game is very buggy. Many cutscenes paused for a fraction of a second before getting going; lines of dialogue would be repeated, or worse, skipped entirely, completely deflating dramatic moments. I couldn’t even invert the camera y-axis! It’s astonishing the game was released in this state. I’m sure these bugs will be fixed eventually, but I cannot recommend playing until then.

I like the idea of story-driven games where graphics don’t need to be lavish, but creators either need to alter their art style to match their capabilities (e.g. using cartoon or 2D art), or reduce the game’s scope (e.g. spend more time on fewer locations and characters). A realistic art style was entirely inappropriate for this game’s resources.

So why did they choose it? Many creators believe, with reason, that players prefer richly-designed 3D games, which is why so many otherwise simple games feel a need to go 3D (e.g. Subsurface Circular). Players want what they want, but they can also be trained to like different things. Story-driven games like The Case of the Golden Idol, Overboard, and of course, The Walking Dead, have all been extremely successful with much simpler, yet still appealing, graphics. Even Star Trek has precedent for simpler art styles in the well-liked Lower Decks.

Abandon realism, return to impressionism! Less is more.

I stopped playing Star Trek: Resurgence after five hours. That’s when I became so exasperated by my tricorder-related travails I couldn’t bear any more. I’m sure the storytelling would continue to be good. It’s a shame about the rest.