PC, Steam Deck

$19.99

Tale of Tales

5 hours

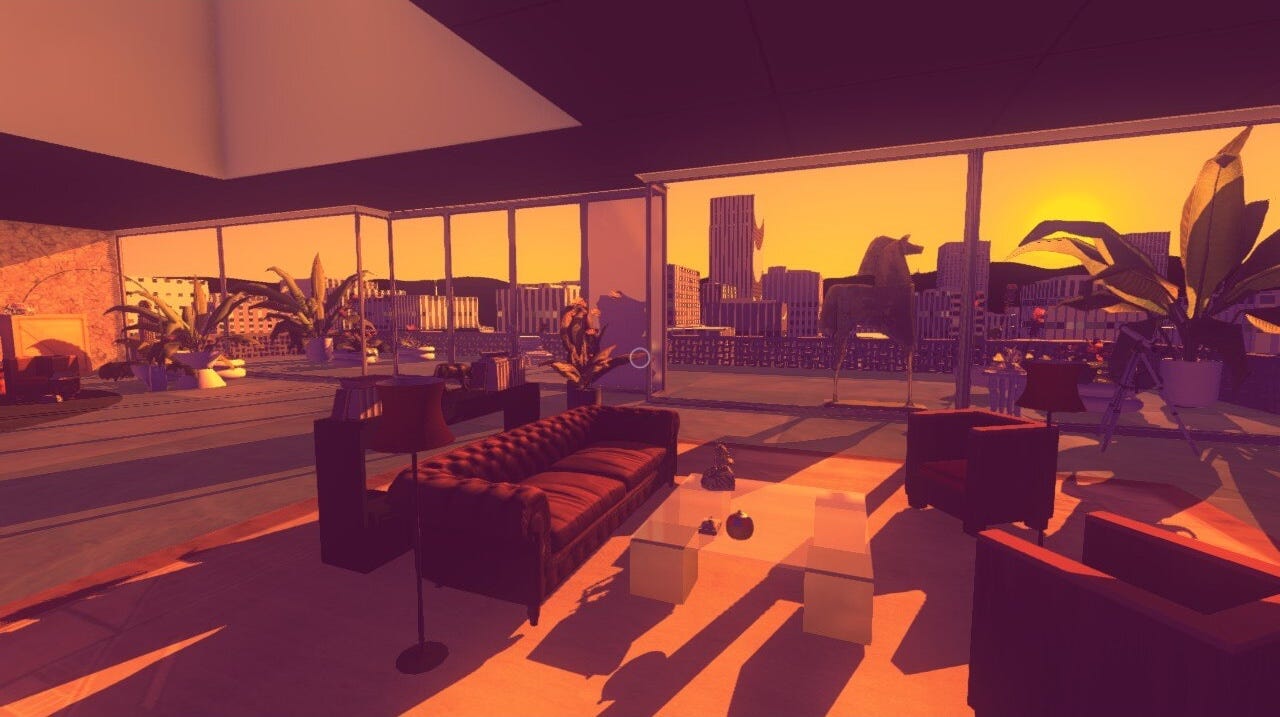

Sunset is a first-person game where you clean a penthouse apartment in the fictional 1972 socialist republic of Anchuria. You arrive at 5pm and leave an hour later, each time learning a little bit more about its owner, Gabriel Ortega, a mysterious art curator.

It’s a simple game: there are no puzzles and no ways to fail. You’re kept entirely within Ortega’s enormous bachelor pad, but the buzz of helicopters and explosions on the horizon never lets you forget there’s the growing revolution against Anchuria’s military leadership – a revolution you shape by passing military secrets from the apartment to the rebels.

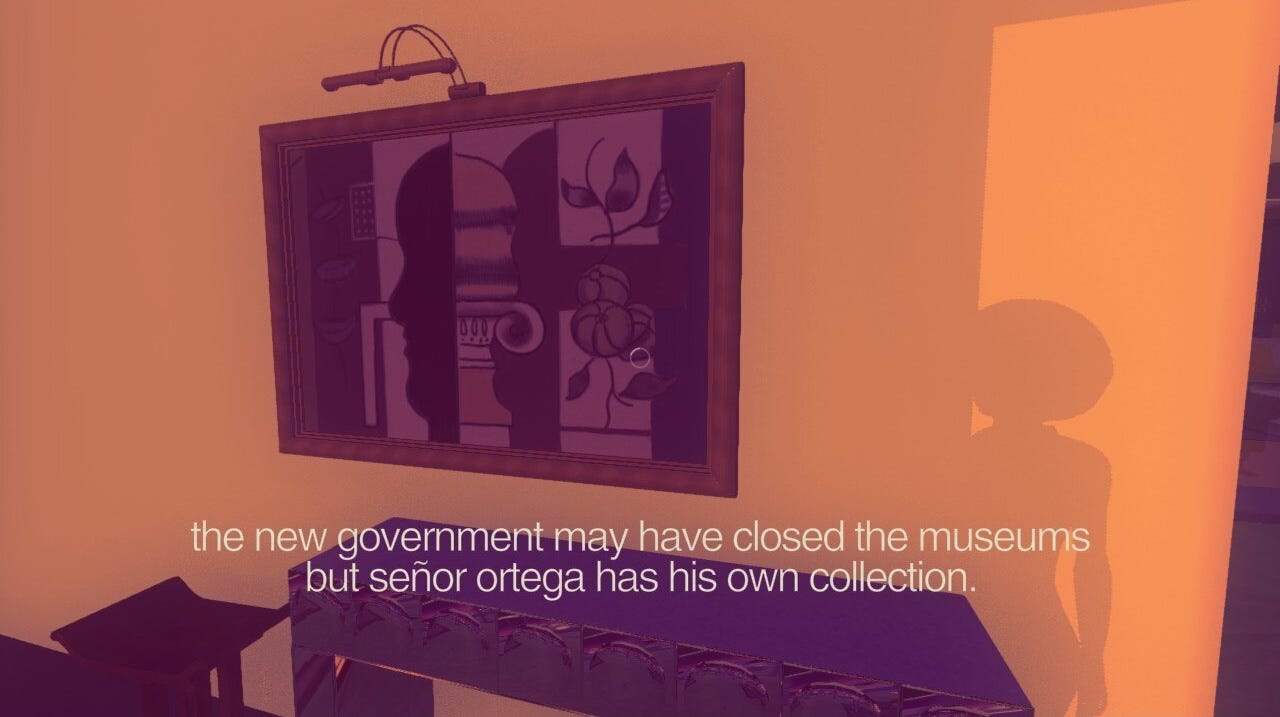

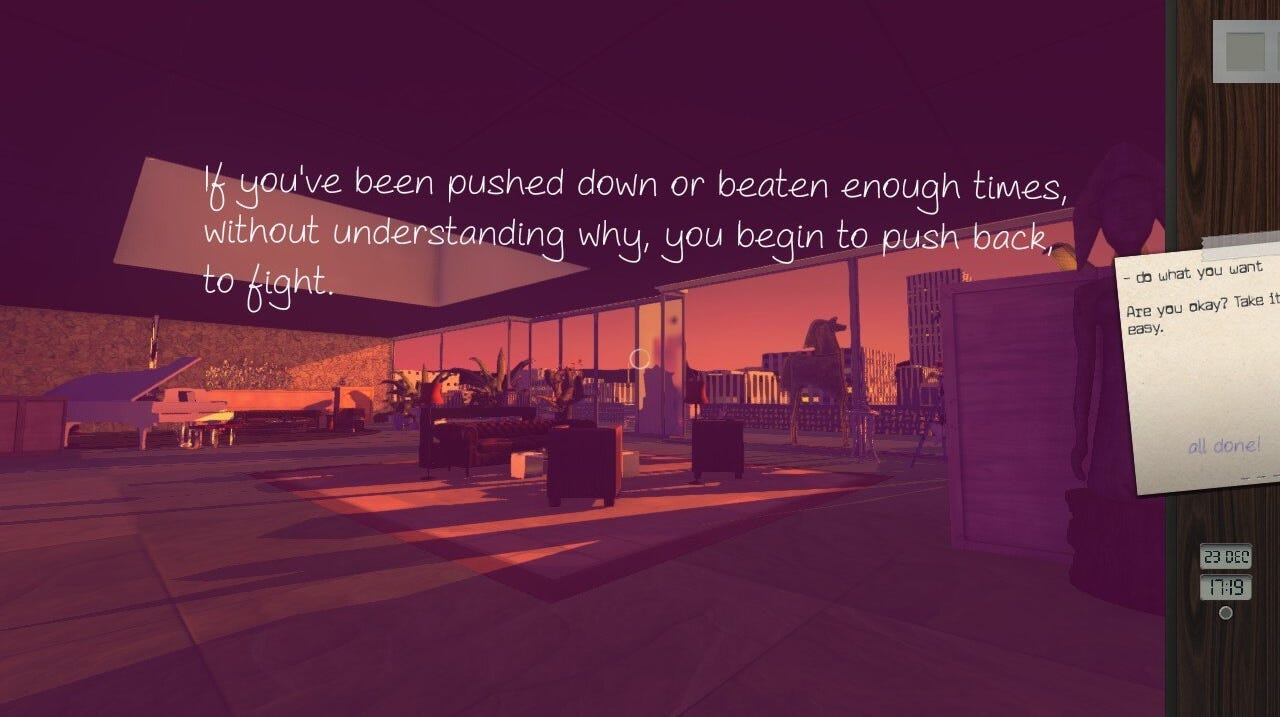

Ortega’s apartment, perpetually bathed in the golden hour, is gilded yet more by the impeccable art and furniture that fills its rooms and walls. It’d be perfect escapism if not for anger and longing expressed by your character, Angela Burnes, an African-American woman whose recently graduated from college. When other games try to tackle hard subjects, they often do so at a remove. Not so in Sunset, where Angela writes in her diary about growing up in a racist America, the ideals of pacifism and the necessity of violent resistance, and how it feels to fall in love with someone she’s never met.

It’s bracingly political – too political for most gamers, who shunned it upon its release in 2015 – yet the chores that occupy most of your time remind you that even in war, life must continue.

I’m friends with the designers of Sunset.

May 21, 1972, Pentecost. You begin in an elevator. In front is your reflection, a task list left by Ortega, and a set of buttons that cleverly stand in for the game’s options. You open the doors to Ortega’s apartment, which is completely empty save some boxes, which you have to move and unpack, giving you a reason to poke around.

Angela talks for a minute after exiting the elevator, musing about her work and recent events; she’ll do the same for your 43 subsequent visits to the apartment. Otherwise, her thoughts are conveyed via text captions when you look at specific objects or out at the city. This mostly works well except for when she’s talking over the captions or when important plot points are delivered at incongruous moments.

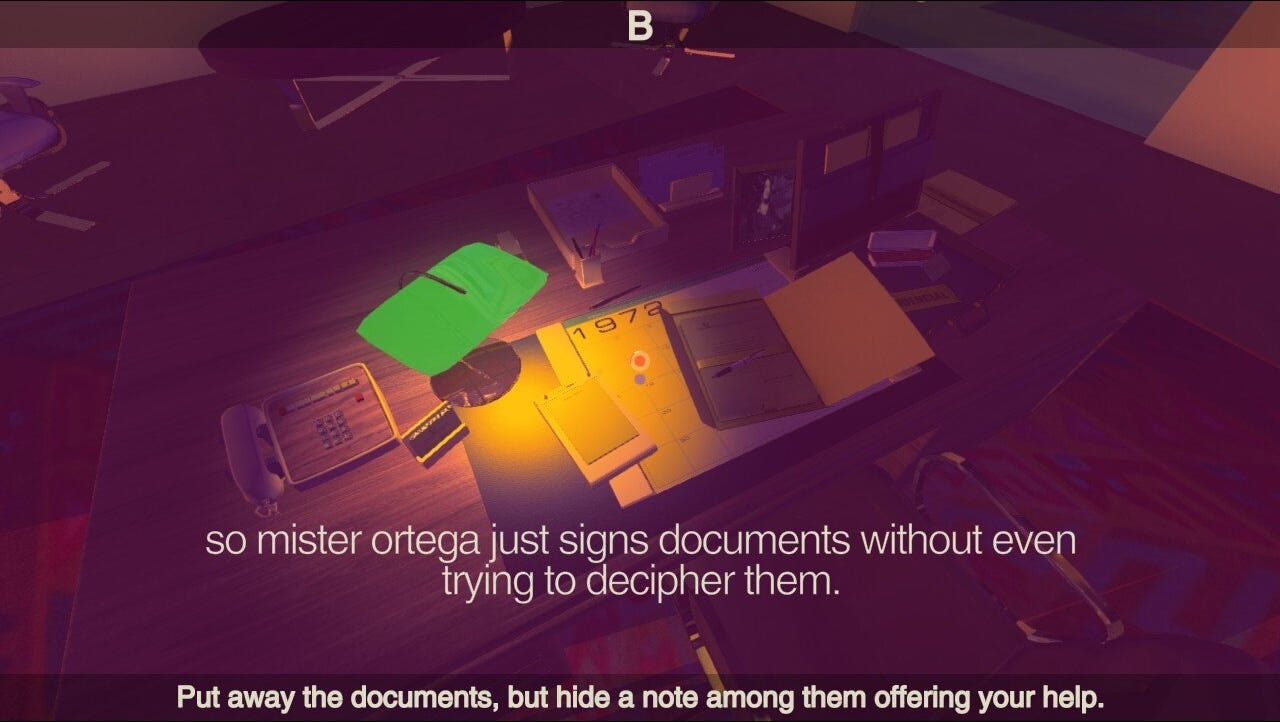

A few objects have actions associated with them. Sometimes there’s just one choice of action, like when you unbox books; sometimes there’s two, like washing dishes brusquely or thoughtfully, or answering a note left by Ortega in a professional or personal way.

There are a lot of oddities to how Sunset presents actions:

Actions are spelled out and described with emotion; it’s not just “clean dishes”, it’s “Load dishes into dishwasher, wash each glass carefully by hand,” a level of specificity that reflects that care that can go into them.

Viewing each choice requires you to look slightly to the left or right, which feels unnecessarily awkward given that they’re mapped to separate buttons.

Once you press a button, the screen fades out and you’re teleported to a new location to see the finished work (e.g. laundry folded and moved to the bedroom, paintings hung on the wall etc.); you don’t see or perform the chores directly.

Some actions consume time: mopping takes 18 minutes, washing dishes takes 30 minutes, polishing silver takes 25 min, etc. Others are performed instantly. The idea is to make you think about what you want to spend time on, because it’s not only binary choices that give you agency in Sunset – you can also ignore tasks and chores completely. Doing nothing is a choice.

Some days, there are more chores than there’s time to complete them and it can be hard to find exactly where the letters are that Ortega wants mailing or which plants he wants watering. Other days, there are only one or two things to do, taking just ten in-game minutes. On those days, I luxuriated in wandering through the apartment, taking in the skyline, noticing what new artwork had been added, and leaving early.

As the hour turns, the light fades, making it harder to snoop around and find notes. At 6pm, the day ends: you can keep walking through the apartment but you can’t interact with anything, and it’s time to take the elevator down again. The one exception is that if you sit down in Ortega’s easy chair at 5:59pm, Angela will write her diary in full, which appears word by word with no audio. Ortega sometimes moves the chair between visits to picturesque spots, leading to a fun hunt.

(I didn’t realise I should sit in the easy chair until I read the instructions a few visits in. No-one reads instructions!)

After a few visits, you settle into a routine of completing chores, updating the wall calendar, and settling down in the easy chair; Ortega’s penthouse may be huge, but you can still walk across its two storeys and patio in 30 seconds. The challenge in Sunset, if there is one, is in noticing things. Not just Ortega’s notes, which might be tacked on the kitchen counter or inside a wardrobe, but spotting a new painting or when the art book on the coffee table has been turned to a new page.

Ortega notices how you change the apartment, too. When you unpack the boxes at the beginning of the game, you can display paintings in a perfect grid or in a more fun arrangement; you can pick what wallpaper to hang, how to repair a broken window (Angela wondered whether Ortega likes the boards I chose, if they give the apartment a “romantic favela feel”), what colour to paint the bar area. These choices persist through the game, small ways to make the apartment feel like your own.

With each visit taking around ten minutes to play in real time, you experience entire months in under an hour. It’s unusual for time to rush by so steadily in these kinds of games; you might get the occasional time jump or opening Up-style montage, not a constant ticking through the calendar. Sunset’s immersion isn’t literal like in “immersive sim” games where you might clean plates wipe by wipe or have stats for your money and health – but it is immersion, an immersion accelerated by montage, with the goal introducing you to a very particular character in a very particular world, as quickly as possible.

Sunset’s story takes place over three acts. The first act begins with your arrival as a cleaner and ends with two discoveries: Ortega knows military secrets and Angela’s brother, David, is a rebel leader. In the second act, Angela begins copying information that Ortega leaves out in the open, seemingly deliberately. He goes on a trip to see his ex wife, encouraging Angela to decorate and learn the piano while he’s away; it ends with David’s capture.

The final act sees the rebels fighting the government openly in the capital. Ortega begins stockpiling art, turning his apartment into a maze of boxes. As helicopters buzz outside and fires dot the horizon, Ortega and Angela work to get the President to step down, their relationship deepening into a love affair, even as they remain apart.

There are a lot of things that seem strange or wrong in Sunset, some of which I assume are accidental or due to time and resource constraints (more on those later), many of which can be explained by the particularities of its design. Here’s what I mean by that: we’re used to seeing broad tropes in games, which is a consequence of how they’re designed to fit into existing genres and targeted toward existing audience segments. Such games are less likely to have speed bumps that get in your way of spending time in them, but they’re also less likely to offer anything very different from what you’ve already played ten or a hundred times.

For example, it stretches credulity that Angela wouldn’t meet Ortega in person over the course of 44 visits, even by accident. But then, missed connections are the entire point of the game, and everything else is arranged to justify that: professional distance, a business trip prolonged by the civil war, Ortega going into hiding, and so on. Too many coincidences, perhaps – more than Chungking Express, a movie that inspired this game – but it just about works, and it certainly works better than seeing him wandering around the apartment.

Then there are the binary choices on how you act towards Ortega. How many people really choose the brusque/professional option versus the personal/romantic ones? Not many, I bet. You have a choice, but it doesn’t feel like one – as Philippa Warr and Emily Short have noted, the personal choices are literally more attractive, described in greater detail and emotion. The intimacy that results from these options feels sudden and disproportionate given how vocally frustrated Angela is with Ortega’s privilege. But again, maybe that’s the point – choices are never equal, especially for someone as lonely as Angela is.

Angela’s diary reveals a similarly fierce, intellectual passion that swings back and forth between naivety and cynicism. Is this the sign of an inconsistent character, or is it exactly how a young woman, recently graduated from university and living in a foreign country undergoing a revolution, would feel?

I can’t excuse everything in Sunset. Angela’s thought-captions are often too broad (“sexy flowers”?), very much out of character with her thoughtful, mournful diary entries. I’m assuming this is a casualty of having to bang out too many one-liners in too little time. And sometimes Angela mentions things in voiceover, like how Ortega has been arguing for her brother’s release, that we never discover from our time in the apartment, as if there were a sidechannel of communication invisible to us.

Sunset’s achievement system is equally jarring, popping up as you “progress” in Angela’s piano practice or her relationship with Orgeta (e.g. “Angela is probably in love with Ortega. Or he with her.”) I can’t imagine anyone other than the most mechanical of gamers wants or needs this to be spelled out in such an atmospheric, narrative-driven game, yet here we are.

I’m fascinated by Sunset’s treatment of the act of cleaning. From a gameplay perspective, cleaning isn’t important at all. Yes, there’s a list of chores to cross off, but Angela notes that Ortega never seems to care whether you clean the dishes or tidy his papers. Sunset tells us that mindlessly completing “mission objectives” merely seduces us with the illusion of progress.

So why clean at all? It’s a choice. In the real world, I take pleasure in cleaning. I used to vacuum and mop the floors of our office, and I still clean our home even though we have a cleaner. If you want it to be, cleaning can be a gesture of consideration and love.

Sunset has many technical issues, ranging from actions and captions being hard to trigger, to the clock not updating properly when you’re meant to arrive late. There’s a uniform lack of polish, too. I accidentally skipped to the next day twice in a row; outdoor sound effects are repetitive and poorly mixed; transitions between locations are too jumpy; some voiceovers are out of sync with the story revealed elsewhere. And given its mechanical simplicity, the game is harder to learn and play than it needs to be.

None of this is a reason to avoid Sunset. I’m reminded of something Jon Ingold said recently:

I blame polish. I kinda hate polish; it’s a thing that makes everything more expensive and prices people out and it’s not really worth anything much - we all forgive the computer all the time anyway; every game camera is clumsy, every texture blurs; every animation clips. You CAN polish a turd but you don’t NEED to cut a diamond.”

Indeed, despite these issues, Sunset received excellent reviews from many critics upon its release in 2015. Unfortunately, it was such a commercial failure the studio soon announced it would no longer make games.

Many of the discussions amongst “gamers” at the time were frightening to behold in their anti-intellectualism and hostility toward the “entitlement” of artists who want to earn a living. The mere presence of books by Kurt Vonnegut in Ortega’s apartment enraged them; only pretentious designers would do such a thing. These gamers demanded to be pandered to; they weren’t looking for polish, they wanted a completely different game.

It’s more complicated than ignorant gamers shunning arty games, though. Sunset’s Kickstarter referenced Gone Home (2013) and Dear Esther (2012), both of which likely sold hundreds of thousands if not millions of copies. A year after Sunset, another arty walking simulator, Firewatch, would sell millions. So what explains Sunset’s poor sales?

Putting aside anti-intellectualism and outright racism, the lack of polish may have discouraged those who were receptive to its themes – but there’s a difference between being receptive and being hungry. It’s not like gamers weren’t aware of racism and autocracies and revolutions in 2015, but I’m not sure they wanted them in their entertainment. But if Sunset were released today, with bug fixes and a decent application of polish, I’d like to think it’d be received rapturously.

That might be optimistic, but more people than ever are aware of how significantly Tale of Tales, the game’s creators, have influenced the industry. The Graveyard inspired one of the best moments in the otherwise violent and frenetic Uncharted 2; The Path inspired The Vanishing of Ethan Carter and The Stanley Parable. Right now, Auriea Harvey, one half of Tale of Tales, is the subject of a major exhibition at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York.

Even if that weren’t the case, Sunset demands attention. It’s about a young black woman fleeing the racism of America; the necessity and cost of violent resistance; and how two people who've never met can fall in love. So many games shy away from politics, preferring to approach those ideas more obliquely. Here, you can’t overthrow US imperialism, but you can choose to burn an American flag. It matters to no-one except yourself.

When asked if they believed a game could players understand what it’s like to live through the horrors of a war or the scary exhilaration of a revolution, the designers rejected utopian visions:

No. I mean it would be nice I guess. But it would be even nicer if such horrors didn't exist at all.

The focus of Sunset is on what happens in regular people's daily lives. Today, we are all living our lives while in the background a war is going on. Maybe not right outside our window, as in the game, but often fought in our name nonetheless, far away from home. Everywhere in the world people are being abused and exploited and oppressed to grease the wheels of capitalism. If the violence is not physical, though it very often is, then it's psychological, social and cultural. Sunset is about all of our lives, the lives we all lead: in our peaceful apartments while the world is burning outside.

And one of the things we try to explore is how a relatively normal life still happens, even in extreme circumstances. We still feel joy, we still sing songs, we still do our work, we still fall in love. And those things are important. So important that, well, maybe they are worth fighting for.

So it was in 2015, so it is now. Sunset is worth fighting for. One day, I hope to play a remastered version – but you don’t need to cut a diamond.

Bonus

I first met Tale of Tales back when I was making ARGs. Fittingly, Sunset has its own ARG including the Anchurian Air website and Ortega’s diary on Tumblr. There’s also an extensive blog of visual story references.

Monday was my final day as CEO of Six to Start, the company I co-founded in 2007; here’s my attempt at summarising those seventeen years.

Finally, I do still intend to move away from Substack – soon!

I played this back in the day. It ran terribly on my MacBook but I liked what it was doing. I remember being bummed out that Tale of Tales closed down shortly after but it didn't come as a surprise.