Super Hexagon

The definition of easy to play, hard to master

iOS, Android, PC, Mac, Steam Deck

$1.99-$2.99

Endless(ish)

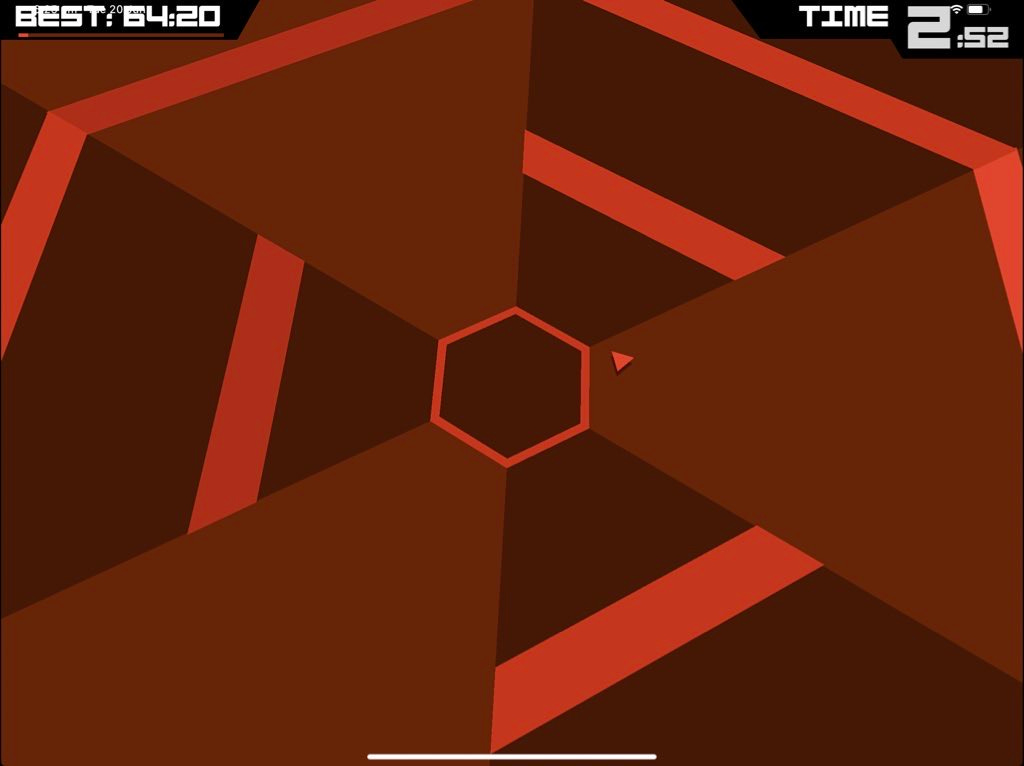

Super Hexagon is an action game where you rotate a pointer around the centre of the screen so it passes through gaps in shrinking hexagons, pentagons, and squares. That’s it!

It’s challenging because the shapes move fast, making the gaps hard to track and reach. New players will die instantly, but restarting takes just a tap of a button, and the pulsating chiptune soundtrack urges you to extend your high score, measured in time “alive”, if only by a few milliseconds at a time. As soon as things get easy, you’re tempted to up the difficulty level, which starts at Hard and goes to Harder, Hardest, Hardester, and so on.

There’s just the right mix of randomness and patterns in the shapes. These have names like “Whirlpool” (where you have to move constantly in one direction), “Ladder” (zig-zagging), and “Triple C” (switching from one side to the other). After a few hundred tries – which is to say, less than an hour of play – you recognise the patterns and don’t have to think how to react.

The difficulty is also leavened by the controls. Instead of players freely rotating their pointer, tapping left and right rotates the pointer incrementally. This means you don’t have to worry about precise values until things start moving really fast.

Super Hexagon has a retro-futuristic style reminiscent of 90s games like Wipeout with blocky, bright solid colours that smoothly morph and tilt in 3D. This isn’t just about looking cool; it’s a way to make the game simultaneously harder and easier. The entire game field is constantly spinning, which seems gratuitous at first until you realise that if it weren’t spinning, it’d be difficult to spot approaching gaps.

But it is also about looking cool. I saw Super Hexagon showcased at Indiecade back in 2012, on a big screen with thumping loudspeakers. Punter after punter strode up to take their chances and like super-hard arcade games of yore, crowds gathered to cheer on the best players.

I’m reminded of David Sudnow’s classic Breakout: Pilgrim in the Microworld (Boss Fight Books, 1983), which relates the author and sociologist’s attempt to understand the rise of arcade games and his own all-consuming obsession with mastering Breakout – yes, the one where you destroy a brick wall with a ball.

Sudnow ends up driving to Atari’s headquarters: not to interview the game designers, but just to get tips on how to play better. Getting home, he would spend fifty hours practicing the first five shots in Breakout so as to achieve perfection. I’m not exaggerating – he’s literally just playing the first five shots over and over and over again, which he calculated at being 15,000 attempts in total.

The book becomes almost unreadable at this point, with his jazz beatnik gonzo writing style working against him. But it picks up again in a bravura passage where Sudnow imagines how Breakout evolved as a melange of raw capitalism and behaviourism, designed to maximise quarters spent per hour. He realises there’s no theory behind the design, no conspiracy, just experimentation and praxis, A/B testing before the tech industry at large used the term.

Super Hexagon was launched in 2012; Indie Game: The Movie was released the same year. Back then, you could imagine a future where games might always be made by scrappy little teams selling them at $5 or $10 a pop to millions of players, not a single in-app purchase or loot box in sight. This was the brief moment after new platforms like Steam and iOS and Android drastically lowered the barriers to game distribution, but before they got completely overwhelmed with games that, in the case of smartphone games, drove the price to zero, or on Steam, saw a race to specialisation and niches. Action games like Super Hexagon – easy to play, hard to master, infinitely repeatable – have become part of the wave of hypercasual games that supposedly started with Flappy Bird in 2017 and are nowadays monetised by constant adverts and in-app purchases rather than a one-off $1.99 purchase that, in retrospect, seems impossibly generous.

I’m not sure how annoyed I should be by this development; but Sudnow wouldn’t have been surprised. To him, action games were arcade games and they were always pay-per-play. He knew every game designer was copying each other; that they were tweaking the difficulty and design as often as they could to maximise engagement; that “an object that remains profitable at the same rate in a coin-op economy no matter how long a single user stays with it – that’s one heck of an ingenious invention.”

He knew this was the future.

I just want to say, Wipeout. So good. Also the creator, Terry Cavanaugh (sic) did VVVVV and Dicey Dungeon? Amazing

Excellent column...but a little odd that it doesn’t mention the key affordance of Breakout Sudnow dwells on, and the thing whose absence makes super hexagon a game i admire more than play: the humbly one-dimensional yet unemulatably precise paddle controller.