PlayStation, Xbox, PC, Steam Deck

$29.99

7 hours long

The Invincible is a sci-fi adventure game where you search for your missing crew on a mysterious planet. You’ll walk and drive across deserts and cliffs, unearthing clues from abandoned bases and robot probes, all while talking to your boss on the radio.

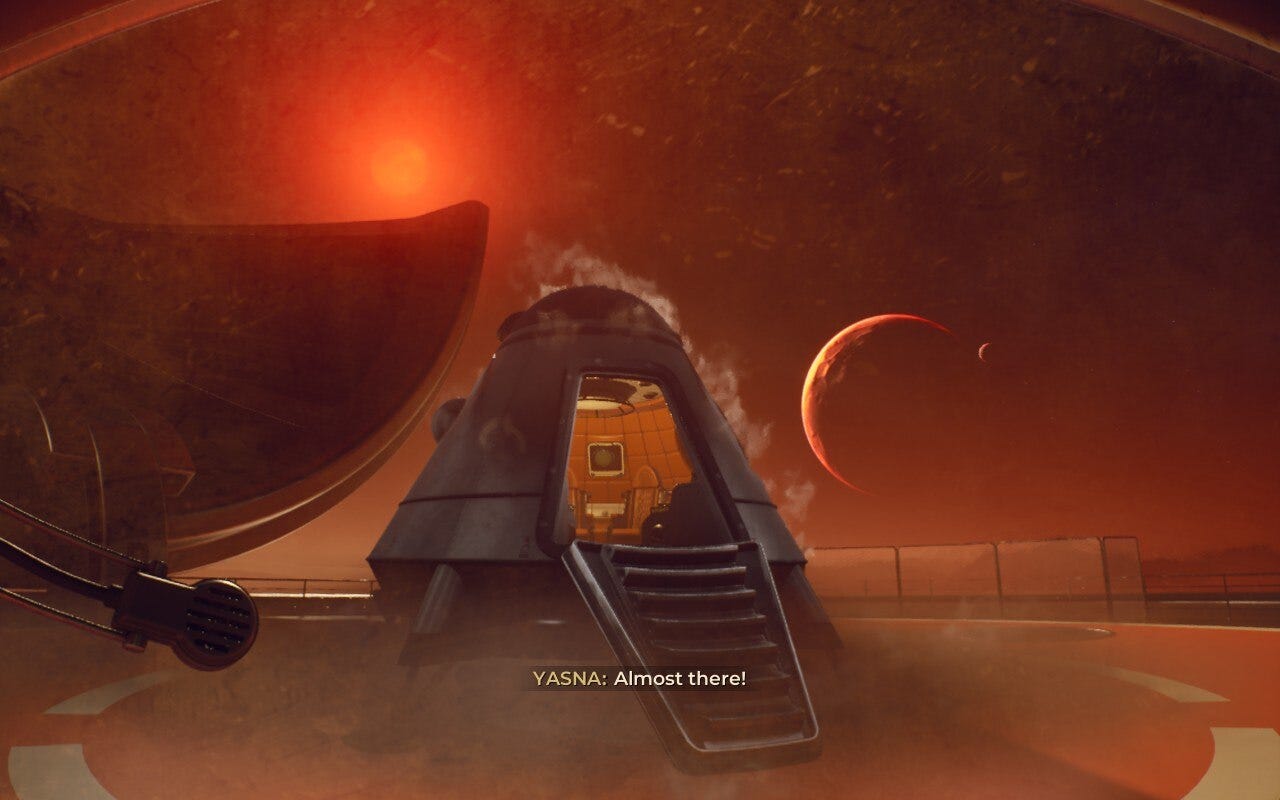

It’s based on Stanislaw Lem’s 1964 novel of the same name, about humanity’s reckless quest to dominate the universe and the nature of intelligence, and adopts a period-appropriate “atompunk” aesthetic: vivid colours, chrome surfaces, ray guns, and flying saucers, everything westerners thought the future was going to be in the 50s and 60s. It’s stunning compared to the drab militaristic style that dominates today’s sci-fi.

On paper, The Invincible is everything I want games to be. In practice, it just doesn’t work.

You play as Yasna, a doctor/biologist on the research vessel Dragonfly. Its crew land on a planet hospitable to life but strangely devoid of it; when they go missing, Yasna is dispatched to find them by Novik, the injured leader of the Dragonfly, who remains in orbit.

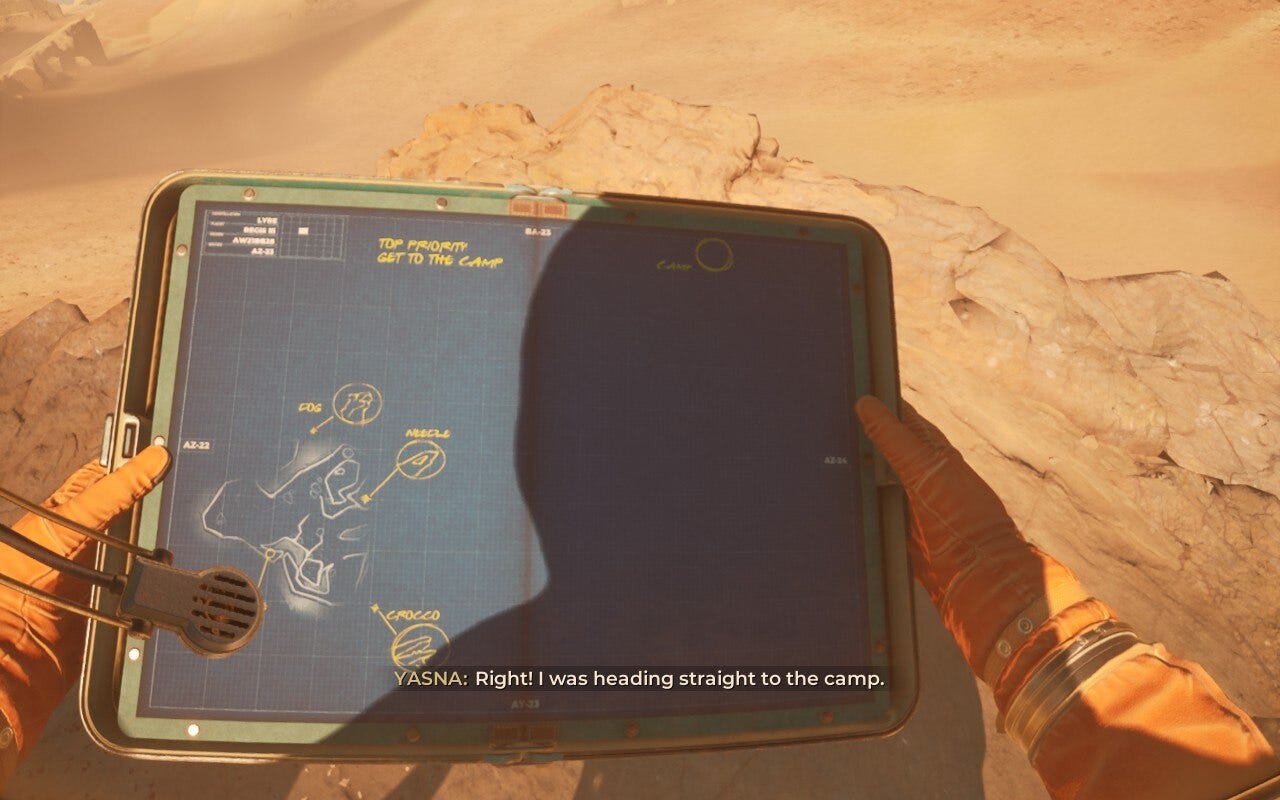

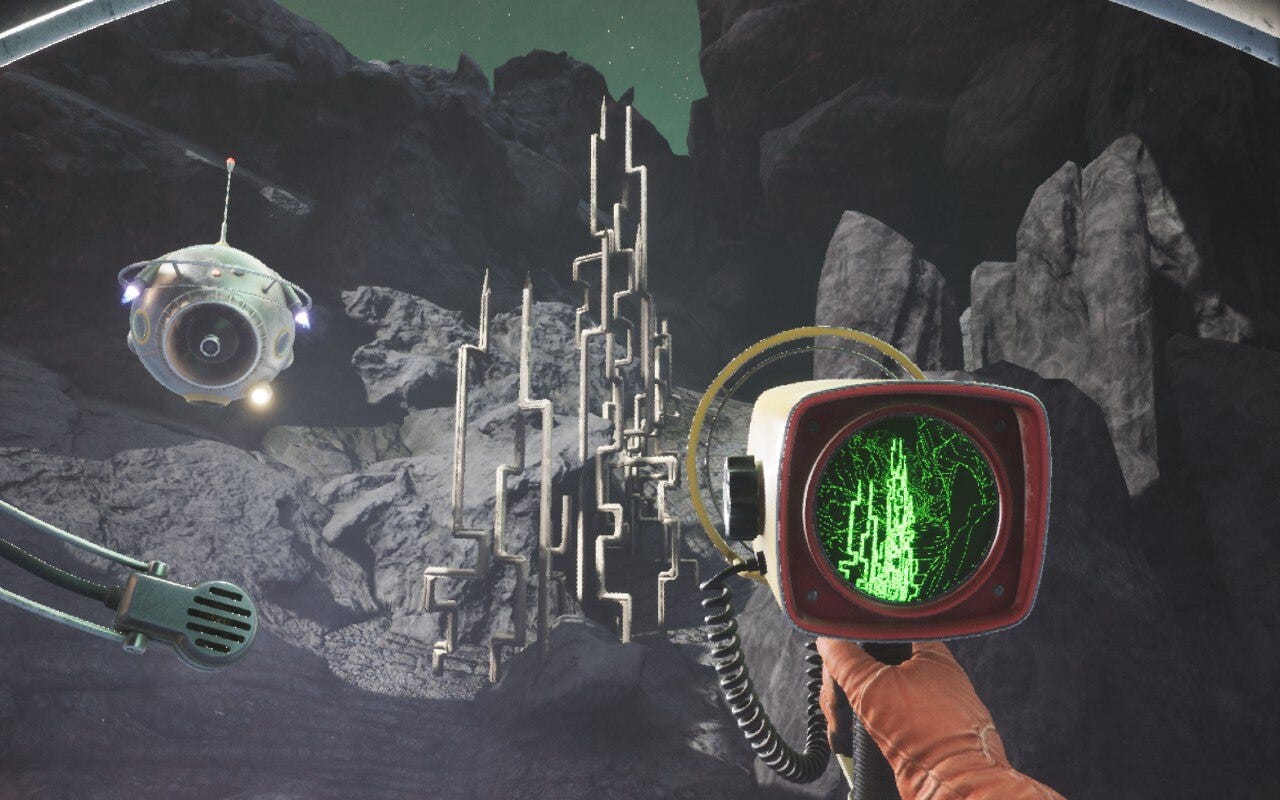

The game begins when you wake up from concussion on the planet. The view is intensely immersive: your first-person perspective is constantly obscured by the rim of your grimy helmet and everything you interact is highly tactile, like your delightfully imprecise “tracker”. Robot probes have control panels that can be opened to reveal stacks of photographic slides, which you page through to learn more of the story; you navigate with a paper map that you literally have to look down at.

Things you can interact with are denoted by white circles; look at a circle, press your right trigger, and you’ll “do” the thing related to it, like picking up an object or opening a door. It’s like a point-and-click adventure but worse, because aiming your entire view is more laborious than moving a mouse pointer. The same method is also used to “report” things you can see to Novik on the radio. During these conversations, sometimes you get three choices about what to say, though usually they aren’t consequential.

Despite a few alternate endings, the game is highly linear, especially on a moment-to-moment basis. Most walking simulators are linear, of course, but they usually have sections where you can choose which of two or three areas to explore next; not so with The Invincible. Early on, I was told to repair an antenna so Novik could get a robot working. I expected some challenge or illusion of freedom, but it really was just pressing one white circle after another. I wondered, not for the last time: if you won’t let me do anything interesting, why not make this a cutscene?

All design is a series of choices, game design doubly so. How fast should the player move? Do we give the rover a big or small windshield? How long should conversations last? How many buttons will we make players press to open a probe’s panel?

There are no right answers – it just comes down to the kind of experience you’re prioritising. There are reasons to have players move extremely quickly, like in action games, and extremely slowly, like when you’re an old woman visiting a graveyard.

At every turn, The Invincible optimises for visual splendour and superficial immersion. I’ve never taken as many screenshots as I did during this game. So many spaces and interactions are handcrafted to produce the most incredible scenes that meld raw natural beauty with space age power. A flashback sees you in the Dragonfly conferring with the crew; a woman slumps on a curved banquette, a cigarette dangling from her fingers, as a man stares through a porthole at the mysterious planet. Later, you stumble into a forcefield that’s sheared through the surrounding cliff, creating circles and arcs around the protective dome.

Just as impressively, the artists take full advantage of The Invincible’s period without becoming mired in steampunk tropes. There are no conventional computers, only punchcards, printouts, and slide projectors. Sleek rockets evoke Chesley Bonestell’s classic paintings, blown up to gargantuan 3D scale; robots deploy antimatter weapons both simpler and more terrifying than the arsenals in modern media. This is a game that spits in the face of generative AI art.

But these choices come with a cost The Invincible is unwilling to pay. The same terrain that’s breathtaking in screenshots is infuriating to traverse. Much of it is impassable, and worse, you can’t tell which bits you can clamber onto until you’re standing right next to them. Moving between two points becomes an exercise in guesswork and frustration, not least because you can only run for a few seconds before becoming breathless. No doubt the designers would say this is realistic – spacesuits are heavy! – but this reasoning falls flat given the myriad other unrealistic things in the game.

When you do find the right place to climb a ledge, the game wrests control from you to play custom animations. These happen so frequently I, once again, wished the game would just drive itself. And for that matter, the driving is both pointless and annoying because it’s so hard to see through your rover’s tiny windows as it bumps along. Immersive? Sure. Playable? Barely.

Yet there are shocking gaps in the immersion. The game superimposes ugly non-diegetic labels on the landscape when it can’t figure out any other way of displaying choices or points of interest, like “OPEN AREA” and “HIDEOUT”. Other games would simply have Yasna speak up automatically when you look in the right direction, or show an icon, or use diegetic symbols like flags; their omission here is hard to explain given how much effort is expended elsewhere.

These labels caused me more grief toward the end of the game when I had to reach the centre of a crater. Because it was filled with laser turrets helpfully labelled “INSTANT DEATH”, I circled the crater rim to find a clever way in – a tunnel, perhaps, like I’d used in other circumstances. Nothing presented itself, so I gave up and walked straight into the crater. The only thing to die was my hope the designers cared at all about players’ experience.

Note that I do not say “players’ enjoyment”. The Invincible, being a fairly bleak story, is not meant to be fun in the conventional sense. The problem is that it gets in its own way too much, as if Schindler’s List made you swap DVDs every five minutes.

Unforced errors abound. While exploring a massive metal structure, you use a handheld “detector” to distinguish stable parts of bridges (bright sections) from the brittle (dark sections). Since the detector’s image didn’t match up with my perspective properly, I fell through the bridge over and over again. This was so aggravating it would’ve been better to remove the “puzzle” entirely.

Editing might have saved the story too, which starts very badly. Not only do we need a moratorium on characters waking up with amnesia, as Yasna does, but we need to ban games where the character is only talking to themselves for the first hour. It’s extremely difficult to write solo dialogue that goes on for minutes at a time without it sounding unnatural or boring, let alone perform it. In my own audio-driven games, I’m always impressed when we find writers and actors who can pull off these feats.

Due to her utter isolation, Yasna is given far too much to explain than the character can handle. As a result, the writers turn her into:

A walking exposition dump, jumping to conclusions faster than what we – Yasna! – have seen and learned but also

The human heart of the story but also

The summariser-in-chief of the game’s lessons.

Throw in the stock lines the game delivers to fill long silences (I heard “this mission drags on so much” and “my legs are so heavy” a dozen times each) and you end up with a character whose words are erratic to the point of insanity. This is not a knock on the actor or even necessarily the voice director but the entire way the story was constructed.

Things improve the moment you repair your radio and start bickering with Novik about crew safety and the mission’s priorities, which would be annoying but for Novik’s mordant edge. Yet this can’t hide all of The Invincible’s storytelling sins, like conversations that go on for way too long, meaning you’re often standing around doing nothing while listening to arguments play out.

The Invincible never quite recovers from these shortcomings, though the story and themes become richer and more particular over time. I revelled when Yasna needled Novik about the superior resources and technology of the Alliance (clearly a stand-in for “the west”) in comparison to their own Commonwealth’s scrappy Dragonfly (coded as eastern/communist). The game also does justice to some very big ideas about the terrifying potential of inhuman machine intelligence on a scale equal to Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem. That isn’t surprising given Stanislaw Lem’s mastery of the genre, but what is surprising are the designers’ additions to the plot, a lot of which work very well (and some of which doesn’t).

And I have to credit The Invincible for handling its intricate, time-jumping plot, involving flashbacks, twists, and multiple cases of amnesia, with aplomb. It’s a grown-up story told in a grown-up way, with refreshingly intellectual dialogue rather than the joke-a-minute self-deprecation we get these days. The story culminates in a series of battles against an unstoppable cloud of machine insects waged by an Alliance officer who, in a darkly humorous portrait of superpowered futility, insists that the next superweapon will surely do the job.

And yet it is deeply unpleasant to play. There’s too much friction and too many meaningless bits of interaction for it to be a traditional walking simulator, but too much dialogue and too little freedom to feel like you have any agency or can even identify with the main character, who is meant to be you but keeps remembering and thinking things you don’t. In the end – and I mean the literal end of the game – you spend five minutes listening to an argument play out with a man whose back is turned to you. The view’s amazing, though!

I can’t help but think The Invincible’s designers are a little too uninterested in video games. If they were more aware of conventions and expectations around traversal and interaction, the game wouldn’t be half as frustrating. Then again, it’s also possible to be too interested in games at the expense of everything else, in which case you end up with games that are pleasant to play but have nothing to say. This is not a problem faced by The Invincible, a game based on a 1960s Polish novel about evolution and machine intelligence and humanity’s insatiable quest for knowledge and control. It has a lot to say.

When every story has the same tired tropes of evil billionaires building murderous AIs, you need to travel further for a different perspective. The Invincible may not work mechanically, but we need more designers humble enough to adapt stranger ideas.

Other games can only wish their failures were this daring.

Stanislaw Lem Recommendations

Stanislaw Lem is one of my favourite authors and perhaps the best science fiction writer of all time alongside Ursula K. Le Guin.

Given the themes of The Invincible, you’d be forgiven for thinking Lem’s stories are tough reads. Well, here’s a hot take for you: Stanislaw Lem is funnier than Douglas Adams. You heard me! The short stories in The Cyberiad and The Star Diaries had me laughing constantly, and their ideas are so imaginative you’ll be flipping to the front and exclaiming, “Wait, he wrote this story about ChatGPT in 1965?!” (Trurl’s Electronic Bard, just for you).

If you like those two, I’d suggest moving on to Fiasco and Solaris. I haven’t seen either of the movies of Solaris, but I liked the 2013 film The Congress quite a bit, which is based on Lem’s The Futurological Congress and is suitably bonkers.

Moving from Substack in 2024

For the past few months I’ve been hoping, rather naively, that Substack would decide to ban Nazi publications. This is plainly not going to happen, so I will be moving to a new platform next year, maybe Wordpress or Buttondown. I’ll let you all know in good time when this happens, and you won’t notice much of a difference!