Viewfinder

What if Portal had bad writing?

Playstation, PC, Steam Deck

$24.99

6 hours long

Viewfinder is a first-person adventure where you place 2D pictures into a 3D world to alter the environment and solve puzzles. As you progress through five levels comprising dozens of puzzles, you learn about the creators of this unusual world, all in search of a device that might fix your own world’s ruined climate.

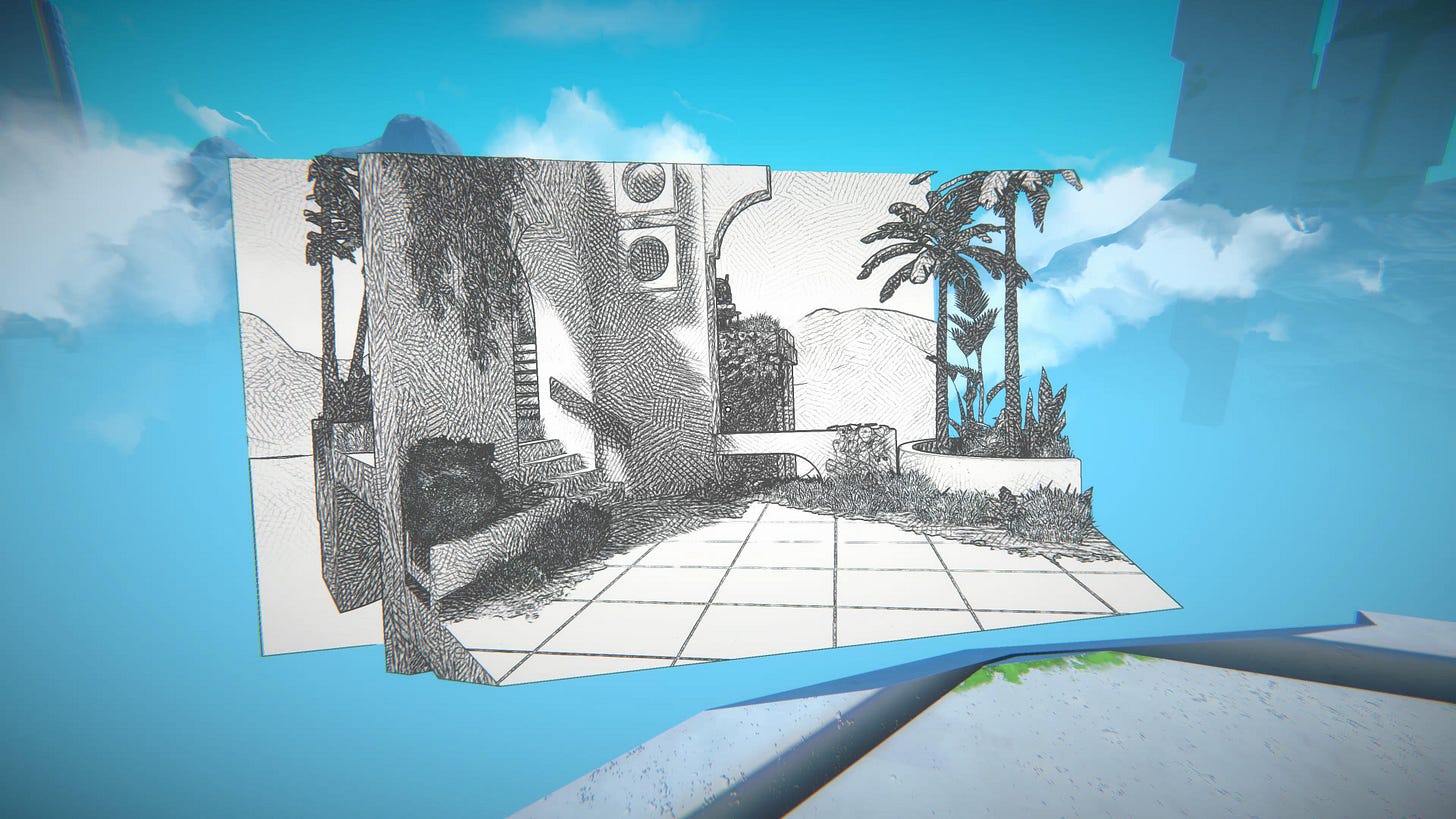

Early on, you collect a photo of the side of a building. When you hold it up and aim it at a ledge that’s too high to reach, the scene from the photo materialises in the real world, allowing you to walk up there:

It’s breathtaking.

I want to take a moment to explain precisely what appears to be happening here. While the photo is a 2D object in the game, it’s best understood as the near plane of a view frustum. A view frustum represents a volume in a 3D world that you can see on a screen, or in this case, on a photo; here, it’s a pyramid with the top lopped off. So when you place a photo in Viewfinder, you transpose everything contained in the view frustum in the photo into the game’s world.

So if you place a photo of the sky, it will replace whatever’s in its way with an empty view frustum volume, letting you shear through a wall (amusingly, the far plane of the frustum – a picture of clouds – is still placed in the game world, a reminder that game engines don’t simulate the world to infinite distance). And if you have a photo of a bridge, you need to make sure the bridge’s depth within the photo’s view frustum matches with where you want to place it in the game world, meaning you’ll need to walk back and forth to get it in the right place.

Even by the end of the game, I still needed a few tries to get the elements in a photo exactly where I wanted them to be, especially when it came to angled surfaces and photos with extreme depth. While placing photos is technically irreversible, Viewfinder lets you rewind time to correct mistakes. Rewinding is a little slower than I liked, but I didn’t realise until quite late that double-tapping the rewind button zips you to your most recent photo-related action.

Things inside photos are considered by the game to be real when placed, like teleporters. These are the goal in each puzzle – step on top of one, and you can proceed. It’s a simple if limited goal, even when teleporters start requiring batteries to be powered or levers to be pulled.

Sometimes you need to rotate photos before placing them, like if the teleporter is sideways. You can also find photos within photos. One early puzzle sees a teleporter on a far-off floating platform far away, so you construct a bridge to it by placing a photo of a walkway “towards” it, and at the end of the walkway is the same photo, so you can keep going.

For the first hour or so, puzzles are of the “use photo on thing next to you” variety; you’ll come to a dead end then notice a photo of an archway lying nearby. But while the game’s environment rarely varies beyond bright modernist buildings with overgrown plants, the style does: if you place a photo with a crosshatched style, the “world” inside will also be cross-hatched.

Viewfinder has a lot of fun with this, extending beyond photos to watercolour paintings, cel-shaded cartoons, a kid’s crayon drawing, all of which become miniature worlds you can wander around once placed. At times, the gimmickry interrupts the elegiac feeling of the empty worlds you navigate; it’s funny to place a photo of a tamagotchi game and get to play with the oversized device, but it doesn’t add anything to the story.

New mechanics are constantly introduced: photocopiers, timers, photos composed of different colour exposures, fragments of photos that, when viewed from the correct perspective, become whole and are automatically placed in the game world. Everything to do with colours felt entirely unnecessary if not actively confusing, like gates that can only be passed through when the “world” is a certain colour.

Conversely, all the photo-related mechanics are hits, especially cameras. These are so overpowered they’re fixed in place at first, so you’re mostly putting things in their view frustum to duplicate them (e.g. batteries). When you get a portable camera, the game quickly limits it with things that can’t be photographed or overwritten. This isn’t bad though: while some mechanics don’t make much sense (e.g. teleporter circuits powered by sound waves), the artificial limitations make for great puzzles. In fact, there was only one outright dud in the entire game.

Oddly, some of the best puzzles are optional. They don’t have any gimmicks and they use only basic mechanics, but they’re quite a bit harder than the rest and, in a way, more imaginative and satisfying for that reason. Because they’re optional, they’re entirely free of story and narration, which was a blessed relief…

It usually takes a while for bad writing to become apparent in a game. In Viewfinder, it hits you immediately. A character named Jessie, evidently watching you from afar, constantly and unnecessarily narrates all your actions. Rewind time? “That’s sick!” Place a black and white photo of a bridge? “Follow the grey brick road!” Connect the final battery to power a teleporter? “It’s alive, it’s aliiiiveee!!! Yeah, too much? Cool.”

Jessie’s enthusiasm is completely out of place with the laid-back, wistful vibe of the worlds you explore, not to mention inconsistent as a believable human being. Not long into the game, it’s revealed that you’re in a computer simulation. Exiting from your simulation dome, you see a polluted red sky. She notes we could find a real “tree of life” in the simulation, or a weather disruptor that could fix the climate. Serious stuff! So back into the dome we go.

This framing device is similar to Assassin’s Creed’s animus, except the animus – a VR machine that lets users relive the experiences of their ancestors – has a convoluted logic to it that provides an excuse for gameplay that wouldn’t make sense otherwise, whereas Viewfinder’s simulation dome never demonstrates its value. To whit: how does it makes sense that photos can be turned into reality?

Viewfinder says: Because this is a computer simulation.

Me: Why does the computer simulation enable this?

Viewfinder says: Because the people who made it decided so.

Me: Why did they decide so?

I have no idea why, and that’s after diligently consuming almost all the audio recordings and diaries and post-it notes left behind by the simulation’s four designers. As far as I can tell, they made the simulation as a retreat where they could create and research ideas like climate remediation. Each designer made their own little world, corresponding to a game level. They all enjoy making art, which leads to the creation of the magic photos, though that’s never quite spelled out. There are also post-its and diaries about puzzles, which I assume is meant to justify why they created these incredible photo-based puzzles that, for some reason, unlock progress in the simulation.

Believe it or not, I’m not a fan of nitpicking “plot holes”. If Viewfinder’s story was of a magician who made a magic camera and magic photos and was hiding a great treasure in a secret photo world with puzzles, that would’ve been good enough for me, and we could’ve skipped all the leaps of logic and had a much simpler setup. Portal’s excuse for having players navigate extremely contrived puzzle rooms was that they designed as an experiment by a murderous AI. In my own Perplex City ARG, we invented a society that exalted puzzles. These might strike you as being even more fanciful than Viewfinder’s setup, but realism isn’t always the goal – it’s getting the audience into the world of the story as quickly and smoothly as possible.

Now, you may say, who cares if the story is bad as long as the puzzles are good? Except it was impossible for me to ignore the story. I didn’t want to, since I thought it’d be important for appreciating the game, or at least solving some puzzles (it wasn’t). But literally, the story is unignorable because people keep speaking to you whether you like it or not.

It’s Jessie who does this at first, but soon enough she’s relegated to infrequent phone calls. These are still annoying because they keep ringing until you answer, plus Jessie seems irritated if you can’t find the phone box fast enough, but better than the constant narration. Unfortunately, a new narrator is quickly introduced: a AI cat named Cait.

Cait seemed less bothersome than Jessie because he’s more laid back, yet over time, I would learn to hate him even more. Every time I would solve a puzzle, Cait would jump in with something banal like “that’s quite a clever solution,” or “I find you to be quite adventurous and fun.” While I was marvelling at a puzzle’s optical illusions, Cait immediately undercut the moment with “it’s a bit clever, isn’t it?”

That’s “just” a dialogue problem. There’s more, though. Cait was created by the simulation’s designers and knows everything about them. That makes his attempts to help us narratively confusing; when he notes that one puzzle is quite complicated, I wondered why he didn’t just tell me the solution.

He also asks the player questions like “why did you come here?” which really didn’t work for me. The bargain in games with silent protagonists like Half-Life and Portal is that players surrender choice and speech on the basis that their character always makes sensible decisions and is never asked a question which, if answered, would dramatically change the story. If you’re playing Portal and a rescuer appears saying “if you give me the word, I’ll get you out of here,” it would be deeply frustrating to sit there, utterly mute, yet GLADOS, the murderous AI, can ask the same question because we know she’d ignore whatever answer we’d give.

So when Cait asks “why did you come here?” we want to say, “I’m looking for a device to fix the climate.” Yes, that would skip a whole bunch of puzzles and make the game less fun, but it’s what a sensible character would say in that situation.

A few hours in, it became clear my time was being wasted. The endless post-it notes and record players tell the story of a group of people who were, essentially, making a computer game. Sure, write what you know, but maybe try to know more interesting things? They argued, they had crises of confidence, they left jokes for each other, nothing special. Their actors had different accents but were indistinct, with the same jokey affect delivering the same vague platitudes. I began walking off whenever someone started talking.

The game ends with an unnecessarily dramatic challenge which must be completed within five minutes – and no, rewinding doesn’t help. Why did the designers introduce a timer for these puzzles and not the others? We can only speculate. Unfortunately, you’re certain to need at least two or three tries, meaning that for the first time in the entire game, you repeatedly solve entire puzzles.

Once completed, you emerge from the simulation dome bearing a seedling. I spoil this without compunction because it makes absolutely no sense whatsoever, and it only bolsters my argument that they should’ve used “magic” as the excuse for everything.

Not long from now, people will ask why Viewfinder wasn’t more successful. It’s technically innovative, the puzzles are great, what’s not to like? Most people wouldn’t think puzzle games require stories, and yet so many of the most successful either have memorable stories that elevate the entire experience, like Portal, Myst, Gorogoa, The Talos Principle, or they have no story at all.

(Hot take: good, short, non-replayable experiences will always end up more story-driven than endlessly replayable games. You can avoid the need for story if the vibe or atmosphere is excellent, or the game is long enough.)

Viewfinder’s puzzles may not be as polished as Portal’s – the inherently vague frustum-based mechanics mean you never reach the feeling of mastery and speed that you get from shooting wormholes – but they’re still very, very good. The problem is that this business is brutal. There’s an oversupply of games and people are looking for any excuse not to play something. If I have to tell you that Viewfinder is worth playing but only if you:

Accept the story makes no sense whatsoever

Don’t read any diaries or post-its

Don’t listen to any record players

Turn off the narrator audio (and maybe even subtitles too)

Turn off the timer on the final challenge via accessibility settings

you might think: fine, I’ll play it after Return of the Obra Dinn and Baba Is You and Her Story.

Games don’t need to be perfect, but they need to succeed at what they set out to accomplish. If you wisely decide to wrap a story around your six hour puzzle game, don’t make it so bad players beg for a way to turn it off.