PlayStation, PC

$29.99

Ironwood Studios

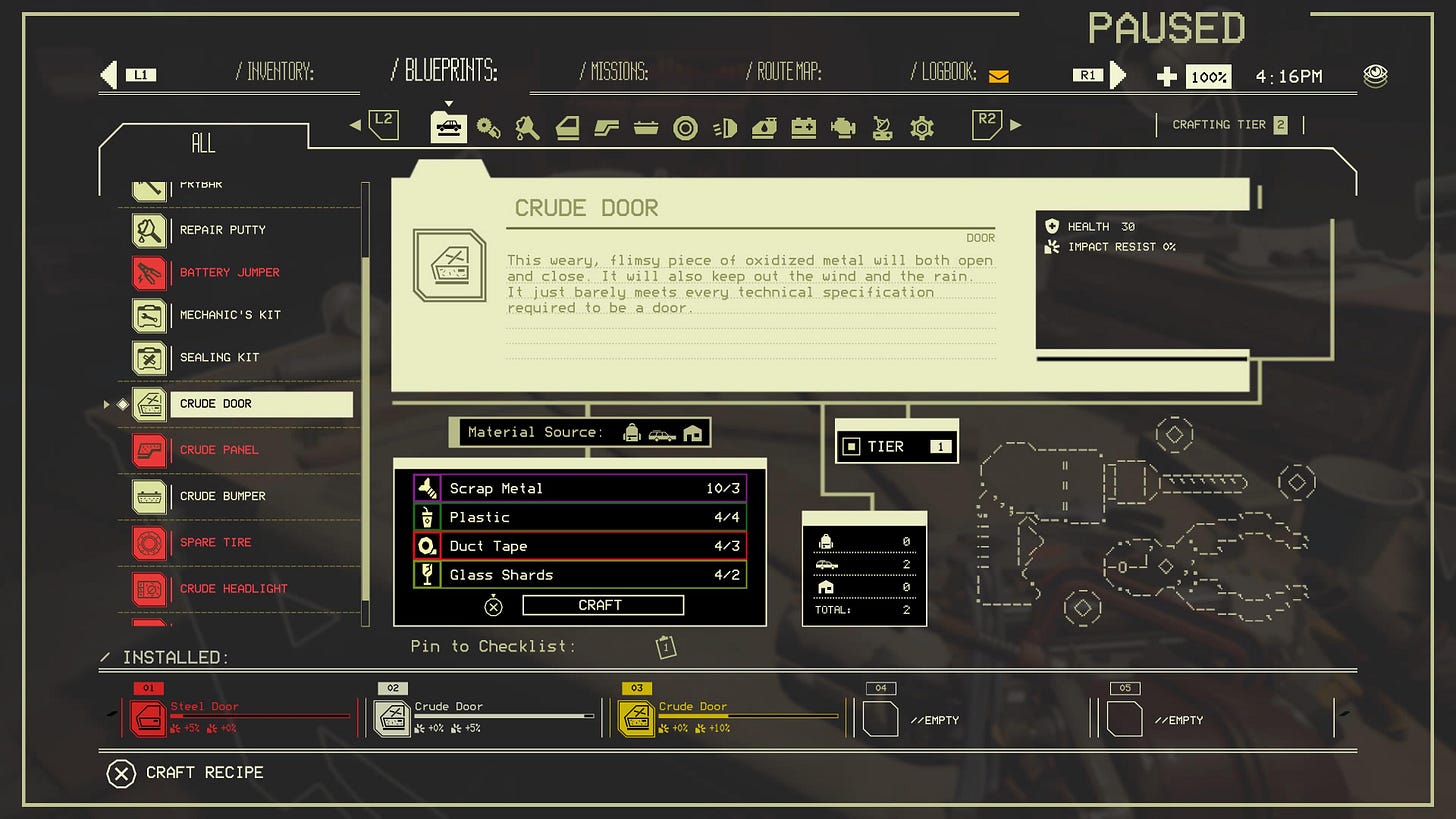

Pacific Drive is a first person driving game where you explore the mysterious Olympic Exclusion Zone. Off-road driving and hostile “anomalies” constantly damage your car, so you spend a lot of time looting supplies to make replacement parts and upgrades that advance the story.

The Pacific Northwest setting, with its 1950-90s period details, is lushly illustrated through procedurally-generated 3D environments and minimalist posters. Throw in the otherworldly anomalies – floating piles of junk, crash test dummies that move when you aren’t looking, portals in the sky, meteor showers, etc. – and the result is an atmosphere that’s both gorgeous and unsettling.

It’s not an easy game to play. There’s far less driving and much more looting and crafting than you’d imagine from a game called “Pacific Drive”. Even its biggest fans surely tolerate rather than love putting their car into “Park” every time they stop, the lack of saves during hour-long “runs” punishes time-constrained PC gamers – and that’s just the start. It was enough to make me abandon the game.

You begin by driving a beat up car toward the Olympic Exclusion Zone, a staging ground for experimental technology established in 1947. Eight years later, the zone was walled off, and over time the borders grew and access points sealed. When you arrive in 1998, huge walls surround the entire area. Naturally, you get sucked into a portal and wake up deep in the zone.

Your car’s controls are highly tactile and “immersive”. You can’t just jump in and hit the gas – you need to look at the ignition key and tap a button. Then you have to look at the gear stick and hold down a button down to shift it into drive. Only then can you get going. The same multi-stage, multi-button fussiness applies to replacing tires, swapping out doors, and laboriously flinging “repair putty” onto disintegrating panels.

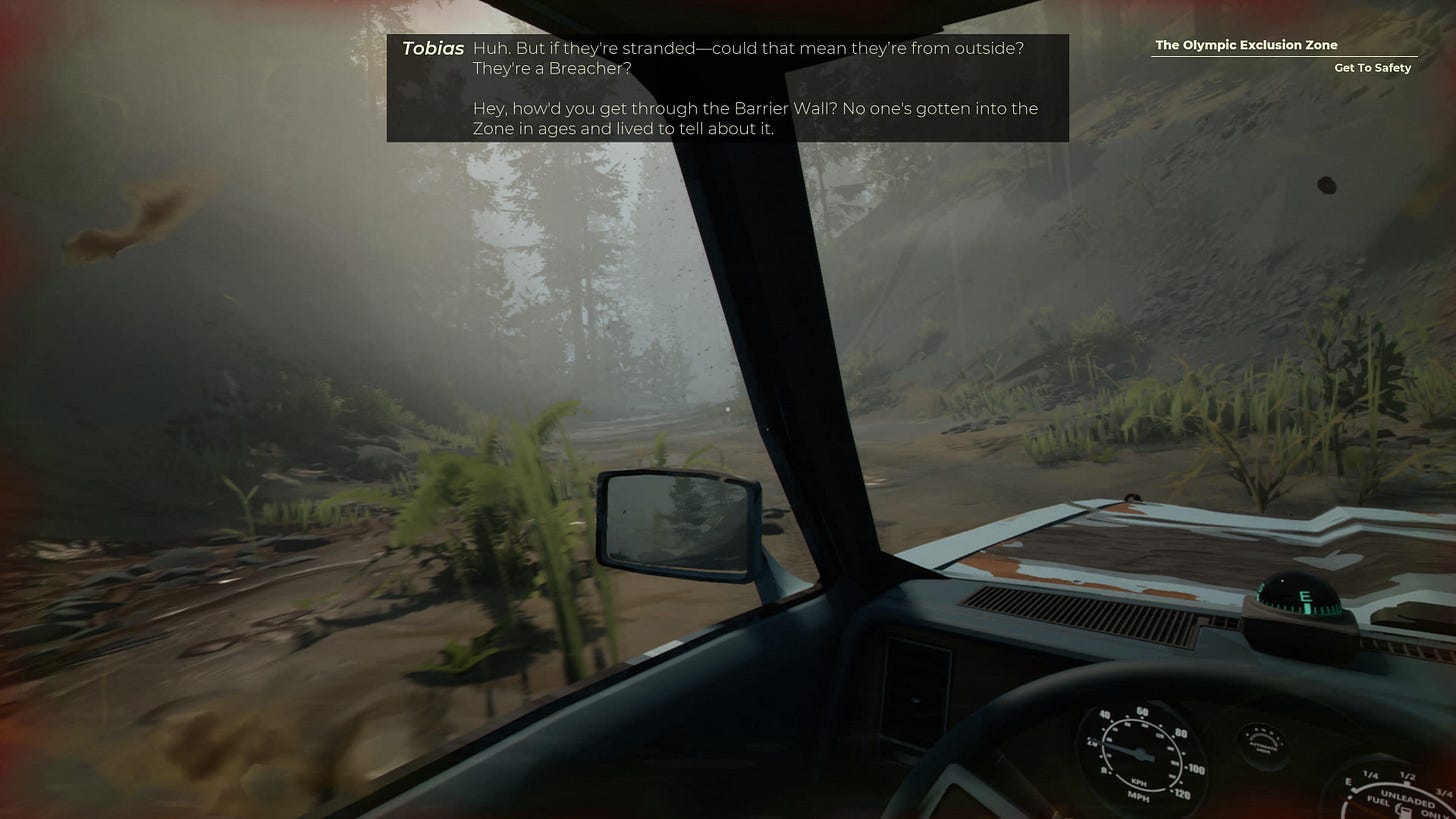

Once your car’s repaired, two voices on the radio, Tobias and Francis, guide you toward a garage. It’s a pleasant drive through woods with weird anomalies to look at and avoid. Along the way, you jump out (putting the car into park so it doesn’t roll off) and siphon fuel from an abandoned car (get fuel can from trunk, walk to other car, look at gas cap, hold down a button to siphon for a few seconds, ditto on your own car).

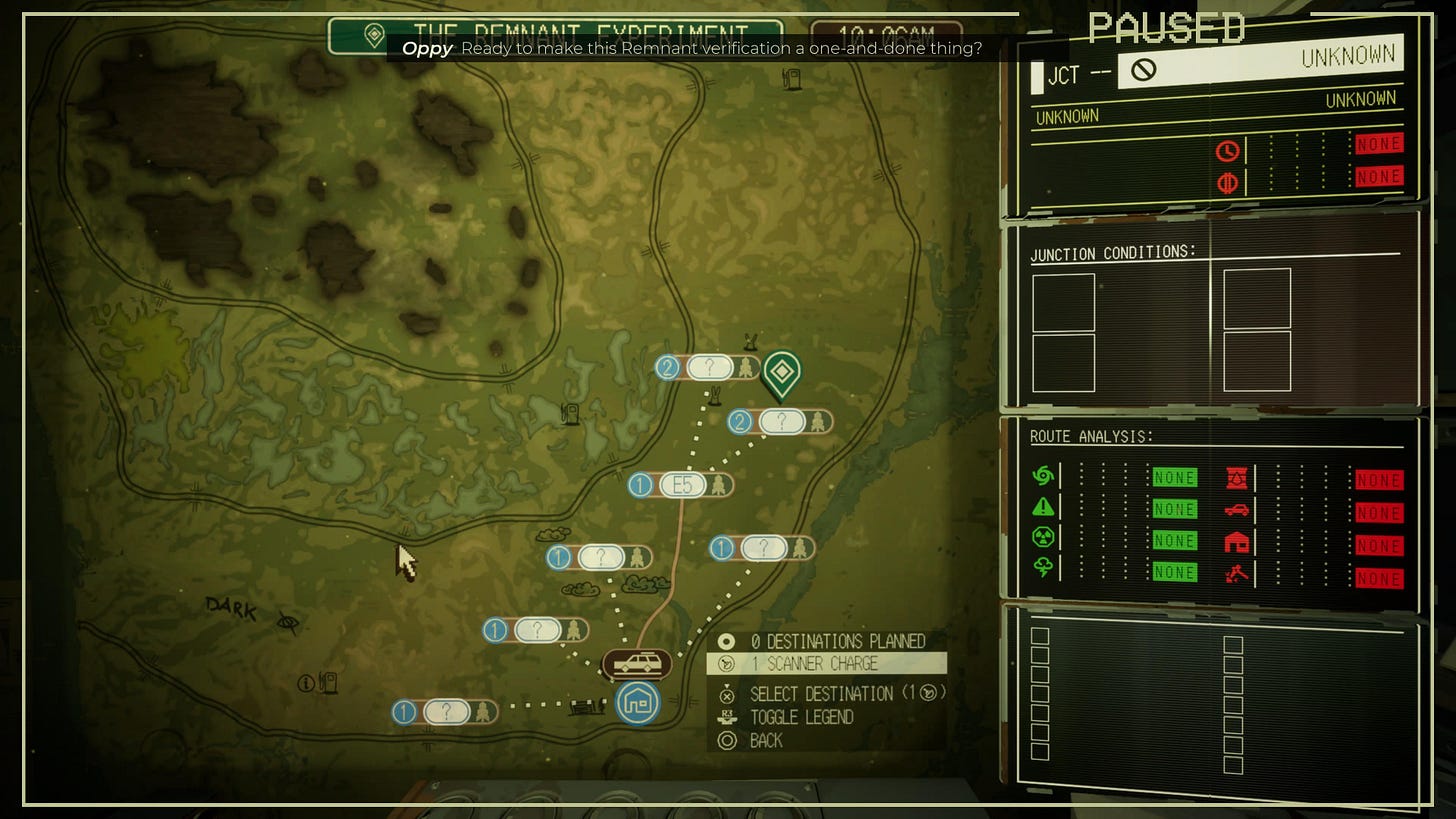

Tobias and Francis explain that your car is a Remnant, a rare piece of technology that still works in the zone, which otherwise renders matter unstable. This is a nice narrative justification for Pacific Rim’s roguelite nature, wherein the areas you drive to change every time you visit. But if you were expecting to be able to drive continuously across the entire game world, Grand Theft Auto-style, think again: the Olympic Exclusive Zone is divided into square regions surrounded by impassable borders, each invariably containing a major road junction.

Travelling between areas therefore requires… teleportation?! Sure, why not! The owner of your garage is a scientist named Oppy. She has apparently invented every major technology in use in the zone, including the ARC device you install in your passenger seat, a combination GPS tracker, power plant, and teleportation enabler.

Sometimes teleporting between areas is as easy as driving through a gate in the road. Other times you have to obtain a “Stable Anchor” to charge your ARC device, a fraught process attracting hostile anomalies, then link it to a “Gateway”. This triggers a battle royale-style storm circle to start contracting around the gateway, its location marked by an awesome pillar of light.

These thrilling races to gateways are not representative of your time in Pacific Drive. I rarely drove for more than thirty seconds before stopping to loot an abadoned shack or government trailer for field repairs or craft bigger upgrades in the garage. In fact, I could barely make it ten seconds without coming across some anomaly barring my way. At first, these electric blue sparks and floating junk monsters were scary, but I saw them so often they became mere inconveniences – not quite the vibe the designers were aiming for.

These constant interruptions plague the game. Early on, I was excited to get out on the open road after a long repair process, until I was prompted to scan some blueprints, refill my fuel tank, and charge the car battery. Immersive, yes – but at what cost? I began thinking Pacific Drive was more like a crafting menu with a game bolted on the side more than anything else; “so… like most survival games” as one wag put it to me.

As in most survival games, your tools don’t last forever. Every time I took apart a wreck with my scrapper chainsaw or broke a lock with my pry bar, I worried about finding enough supplies to craft replacements. Some people like breakable tools, god bless them, but not me. I understand the appeal of wanting to live inside a game – there’s a level of familiarity and mastery over a game’s systems that can be intensely satisfying, or at least, distracting. I’m just not sure how broad that appeal is.

I personally don’t find it interesting to scrounge through toolboxes and shelves for duct tape and bits of glass, or to inch my way around the hundredth anomaly blocking the road so I can reach an identikit trailer that may or may not have the chemicals I need to progress the story. The elements of Pacific Drive that “time waster” players enjoy are the same ones that prevent me from appreciating its world and story.

One could argue my complaints are like saying Tetris doesn’t have realistic graphics, that I simply don’t understand what this game is trying to accomplish, but I’d flip that around. Pacific Drive is very deliberately designed as a finicky, “immersive” game aimed at people who like that kind of thing. Since they also want to attract more casual players, the designers offer lots of gameplay and accessibility modifiers to make things easier; for example, you can turn off the entire “car quirks” system that opens your car trunk when you reverse. But because finickyness is so inherent to the game, there isn’t a modifier for extending tool durability or the million other chores that get in the way of appreciating its non-finicky aspects.

Pacific Drive’s setting is almost enough to pull me through. It’s reminiscent of Firewatch’s beautifully-lit vistas, surely a key inspiration for the Olympic Peninsula’s 50s-style park theming. When you crest a hill and see a dark megastructure rising out of a plain, it’s hard not to be intrigued. But the game’s other spooky inspirations – Control, SCP, The Lost Room, STALKER, Tales from the Loop, etc – are all too familiar. Weird things floating in the air, redacted government records, improbably dramatic transcriptions, tales of scientists’ hubris – they’re just… boring now.

Plenty of games have rote plots that are saved by excellent characterisation, but not this one. You hear plenty from Tobias and Francis and Oppy but in the few hours I played, it was pure plot – “I bet you’re dying to hear about Remnants!”, “Driver, watch out for the [anomaly] bunnies, they’re a doozy!”, and so on. I can’t help but think these jargon-filled data dumps might have been better conveyed through environmental storytelling or spread out between more chat. Either way, their explanations are altogether too casual for the genuinely horrific place they live in, as if living in the zone is no inconvenience at all and witnessing the first human in history to teleport (you) is barely worthy of comment.

Oppy is insulting and regretful, Tobias and Francis are enthusiastic, and that’s about all I could tell you about them. Left out are any other elements of their personality, not to mention exactly why they’re helping you and what the stakes are. Oppy’s motivation for entrusting you with her wondrous ARC device is literally getting you “out of [her] hair.” I’m sure if I kept playing I’d learn more about what everyone wants and how they’ve managed to survive in the zone for so long, but motivations should make sense in the moment, too.

Ignoring the story could’ve been an option if it weren’t for the checklist in the corner of the screen tracking the next story-related tasks, muting any impulse to explore the world. I’m perfectly happy with linear stories, but it’s an odd choice to tell one in a procedurally-generated game with so much busywork.

The checklist underpins Pacific Drive’s tutorial that guides you through repairing your car with nested tasks. This worked swimmingly until I put on Oppy’s “Mechanic’s Eye”, a pair of goggles that layers icons and information over the world. Everything I looked at seemed to have four different actions I could perform on it, indicated by tiny icons with contextual controls where tapping a trigger does something different than holding it, which is how I threw away my pry bar while trying to scrap a car.

When I couldn’t find it, I wondered if I’d have to restart the game until I realised I should use the nearby “scrapper” chainsaw instead, a task that was mysteriously omitted from the checklist. Pacific Drive is hardly the most complicated game I’ve played – Against the Storm has much more going on – but it’s yet another odd choice to begin with an exhaustively complete checklist and then give up any attempt of explaining things half an hour later, whether that’s the tools or the utterly confusing stability scanner/mapping system.

I honestly can’t remember the last time I was so excited for a game but ended up so completely unable to play it. There’s an early area where I had to get onto a bridge, which involved a lot of off-roading in the dark. I couldn’t see anything because one of my headlights was bust and I didn’t have the blueprint to fix it, so I kept bumping into things that damaged my car, meaning I had to get out every minute to repair it – a task made harder because I didn’t have a torch. Immersion!

This is the point at which fans will say I should’ve turned on car invulnerability and “brighter nights”, which I did, but only after a great deal of frustration. Pacific Drive is one of these new kinds of games that disdains easy/medium/hard difficulty settings, instead giving players dozens of individual modifiers to tune the game to their liking. The problem is that as a new player I have no idea what I should pick – which is precisely why games offer global difficulty settings in the first place.

Again, the absence of torches and difficulty settings are not technical issues, nor is the fact that your GPS is only visible if you look to the side. These are not technical issues. They’re choices to make the game harder and more “immersive” – but not so immersive that refuelling takes two minutes rather than ten seconds, or that you have to do oil changes.

Other problems may be harder to fix. There’s no way to save your progress when you’re away from your garage on “runs”, apparently due to the game’s procedurally-generated maps. This means you could be on an hour-long run and die right at the end with very little to show. Yes, you can turn off “item loss on failure” to remove much of the sting, but if it’s a story mission, you’ll probably have to redo the whole thing. And while I played on a PS5, where suspending the game is easy, this is much trickier for PC players. Other roguelikes I’ve enjoyed, like Hades, Elden Ring, Against the Storm, and Brotato, are nowhere near this punishing.

Then there’s the motion sickness. Pacific Drive’s restricted field of view wasn’t a problem for me when I was driving on smooth roads in daylight, but when I was off-roading at night with a busted tire and glancing at my GPS every 15 seconds, I felt very queasy. I accept this is an individual issue and others won’t be bothered, but it’s a shame nonetheless; certainly I didn’t think the driving would be as tough as it was.

Finally, I ran into a tricky soft lock when collecting an Anchor to power my ARC device. Since you can only carry one thing at a time in your hands, I had to drop an important mission item, which for some reason I couldn’t put in my backpack. But as soon as I picked up the Anchor, the ground started heaving around me, so I lost track of the mission item. I spent a few minutes rooting around in the woods for it, to no avail. In the end I repeated the entire run. I expect this, and other soft locks, will be fixed, but it’s a reminder to avoid playing games on their release day.

On a later run, I lost an Anchor during a storm and couldn’t figure out what the story wanted me to do next. I returned to the garage to discover my next major upgrade needed lots more scrap metal, for which I’d need to saw apart a bunch of abandoned cars. This wasn’t my idea of fun, so I stopped playing.

Pacific Drive is caught between two very different kinds of games:

Classic roguelikes with emergent gameplay deep enough to withstand hundreds of runs over procedurally-generated levels.

Narrative adventures with levels hand-crafted to fit a linear story.

Neither of them truly work here. The story is diluted by the endless procedurally-generated looting, and there’s little emergent gameplay because the anomalies are so isolated and the story dictates a linear progression in abilities.

The lesson? In game design, it’s best to pick a lane.

Thanks for the review. The game managed to get a lot of good press so I found your take on it refreshing. Pity about the driving being so stunted. I like the idea of a more immersive driving simulator, but then it should last longer than a few seconds at a go!

"Pacific Drive is one of these new kinds of games that disdains easy/medium/hard difficulty settings, instead giving players dozens of individual modifiers to tune the game to their liking." This is perhaps a remnant of my being old, but to me that feels like cheating. There is a "correct" version of the game, and it's the one that comes out of the box. I realize that's not true, and I'd never tell anyone not to tweak a game to suit their preference/need/playstyle. But it bugs me on a foundational level.