Starfield

At least the portions are big

PC, Xbox, Steam Deck

$69.99, free on Game Pass

50+ hours

Starfield is a sci-fi action roleplaying game where you undertake quests across hundreds of planets, moons, and space stations. Quests typically require shooting enemies and saying the right things to non-player characters (NPCs). Ensuring you have sufficient weapons and abilities to complete harder quests means collecting money and items from fallen enemies and stealing everything in the universe that isn’t nailed down. You can build multiple bases to automate resource extraction, staffed by friendly NPCs, to help you craft more powerful weapons and upgrades.

In other words, Starfield is a classic open world RPG in the vein of Bethesda’s previous Fallout and The Elder Scrolls series, respectively set in post-apocalyptic and fantasy worlds. Beyond cosmetic changes and upgrades, Starfield’s main innovation comes in its scale – space is big and you can fit a lot of places to visit in it. Surprisingly, this is Starfield’s downfall, as the game can’t reconcile the heady possibilities of letting players go anywhere, any time with the expectations of sci-fi storytelling.

Starfield begins by asking you to customise your character’s appearance and background. Your background isn’t especially consequential – it determines the three Skills you begin with (e.g. the ability to pickpocket, extra health, improved stealth) but you can add new Skills every time you level up, and while it unlocks the extra dialogue options, these feel very rare.

You also pick three Traits like Dream Home (get a free house with mortgage), Extrovert (use more oxygen when adventuring alone) and Hero Worshipped (an “adoring fan” will show up randomly and talk at you, but also give gifts). These are a bit more fun, if rather confusing to new players, and similarly weightless in nature.

So it goes with the rest. The story kicks off with you as a miner. You discover a magical artifact that when touched elicits a vision of stars, a vision so overwhelming that your character agrees to throw themselves into intense firefights in order to bring the artifact to a friendly group called Constellation. Constellation are a friendly group of explorers who like exploring; why they are special is never explained given that one assumes governments and scientific institutions would also be searching for new resources and discoveries. Evidently the designers wanted the “good” parts of the Age of Exploration without the bad (racist, colonial, extractive) bits.

In any case, Constellation only recently became aware of the artifacts. They appear to be of non-human origin and when they’re brought together, they float and emit interesting radiation. Thus your quest: collect artifacts by flying to various planets to track them down, shooting any bad people in the way, or persuading them to back off. It’s the most uninspiring setup for an RPG I’ve seen in a long time, and it really didn’t help that the magical “vision” is deeply unimpressive.

It’s not terrible, it’s just the definition of mid. The acting is decent, the characters look fine (though there’s no blocking to speak of), the dialogue is serviceable, though overwritten to the point where I speedread the subtitles of every conversation, hammering the skip button as fast as I could. Combat is a perfectly average experience where you juggle the usual set of weapons to chip away at enemies’ health bars, whether on the ground or in space. The RPG mechanics add a bit of depth through status effects like torn muscles or radiation poisoning that reduce your ability to jump and sprint; plus you can sink a lot of time into crafting weapons upgrades and pharmaceuticals, but the game barely bothers to explain why this is interesting.

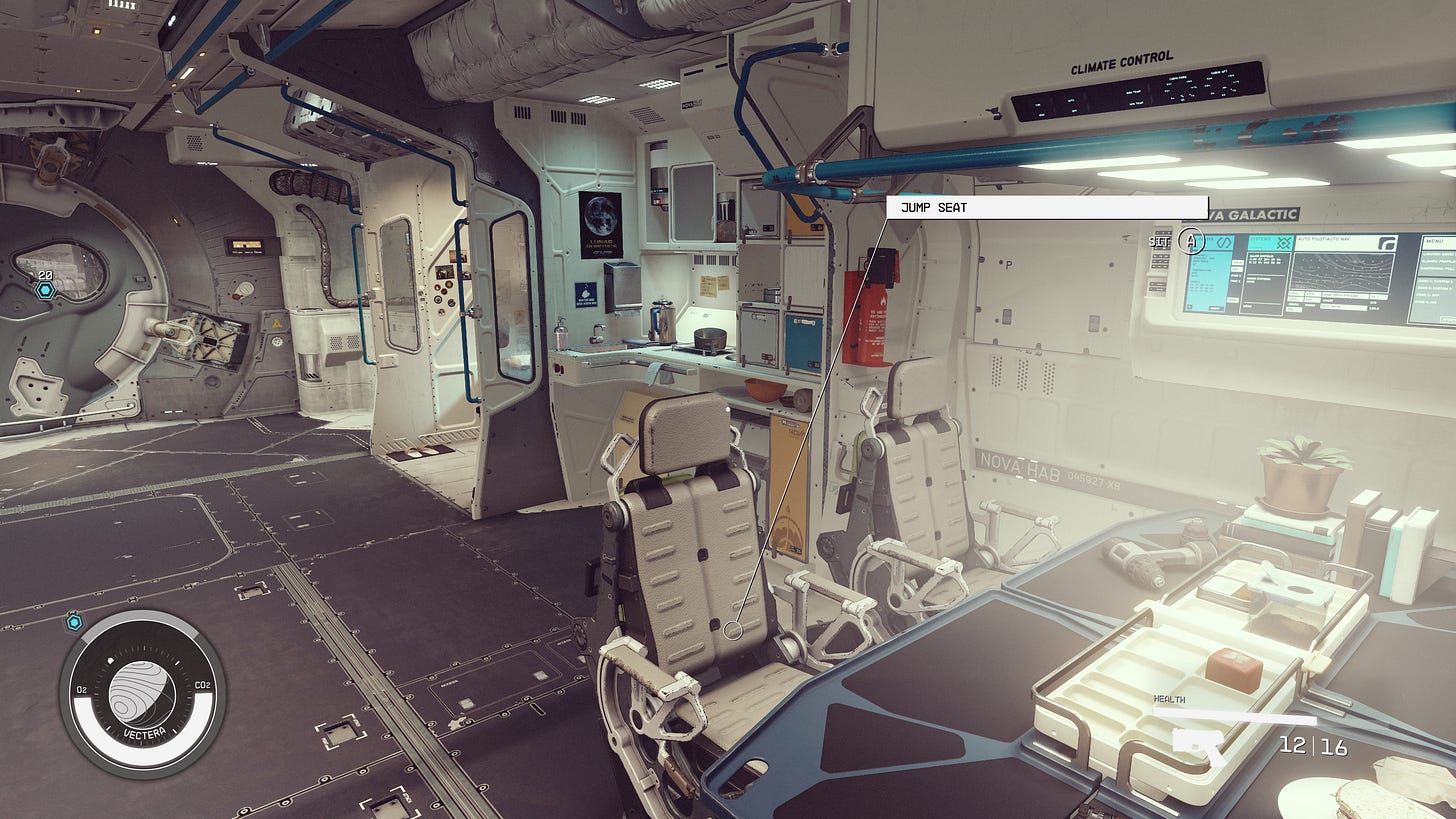

If Starfield’s story and combat are mediocre, the only thing to account for its popularity is its open world. Not only is it astonishingly detailed, with every spaceship and town and city filled to the brim with NASA–inspired 2000s chunky clutter, but it’s bigger than ever. I played for nine hours and I doubt I’ve seen a tenth of the locations; I can’t think of another single-player RPG that even comes close.

The ability to freely run across large, varied locations filled with people to meet and missions to discover and things to collect and steal is arguably unique to Bethesda’s games, at least in terms of graphical detail and depth of character interactions. Indeed, it’s so detailed it’s hard to know which things you can pick up and which are merely cosmetic. It’s genuinely delightful to wander around new places, looking at posters and gawking at what the designers have come up with. For many, this is worth the price of admission, even with generic combat and story. Sure, the extreme freedom means your character will occasionally fall off a walkway and become wedged in a gully, but that’s an understandable flaw.

You’re drawn into exploring the world through quests. As you search for artifacts, you’ll overhear characters talking about treasure, or you’ll receive a distress call while in orbit. These leads get added to your list of sidequests automatically, meaning you’ll never be a loss for things to do, all of which you can start and abandon and resume at will. Some are low stakes, like helping a bartender retrieve ingredients; I persuaded a security guard to look the other way by choosing the “right” dialogue options. Most involve combat, like killing a pirate captain in an abandoned research tower, and some are quite long; I once spent an hour clearing out a base overrun by faceless baddies. I chuckled at a couple of sidequests’ stories that leaned into absurdity but speedread my way through the rest.

What Starfield’s quests lack in substance, it makes up in volume and ease. Every quest comes with a to-do list and a shortcut to fast-travel to the relevant location. This is helpful, but by flattening the literal space that Starfield occupies, it marks the game’s descent into incoherence.

Let me elaborate. Starfield’s map has four levels of zoom:

A galaxy map that plots star systems.

Individual star system maps show their planets, moons, and space stations.

Planets and moons can have their own map, showing cities and other points of interest on a globe.

Specific areas have “surface maps” showing areas within a city.

The galaxy map is somewhat useful because your ship’s grav-jump drive has limited range, meaning that if you want to go from one side of the galaxy to another, you’ll have to make some pitstops. It is also blessedly simple unlike the three other map types which have user interfaces so awful I spent 30 minutes at the start of the game totally lost because I’d selected the wrong landing point.

But better UI wouldn’t solve the ultimate cause of the confusion, which is that on many planets Starfield lets players land at arbitrary locations containing barely anything of interest. I assume this is because a small number of disproportionately influential players mistakenly believe that being able to trudge across featureless plains is “fun” and “immersive”. In reality, most players will fast travel from one quest objective to the next, a jump across ten lightyears indistinguishable from a journey across ten kilometres.

When everything is equidistant, maps are meaningless. As Tom Friedman would say, Starfield’s universe is flat.

True, most players choose to fast travel in open world games even when continuous travel is possible across a single unified map. The difference is that continuous travel is essentially absent in Starfield. This is inevitable – space travel in games requires either faster-than-light travel or a compression of space. Outer Wilds opts for the latter, which makes it a much shorter and better game than Starfield. The former has been done far more elegantly by games like No Man’s Sky and Elite Dangerous, which are even bigger than Starfield and focus more on simulation than story.

This is wise because when you make hopping between stars trivial, traditional notions of exploration and economy and frontiers and conflict are shattered. Starfield acknowledges this to an extent: practically everywhere you go, other people have gotten there first. In fact, most quests aren’t going boldly where no one has gone before, it’s mediating in disputes and shooting baddies. One suspects the real reason for setting this RPG in space was to make it convenient for armies of developers to designing planets and star systems in parallel.

Why even pick space? Why not continue with fantasy or the post-apocalypse, both of which have more of an excuse for RPG tropes like combat, resource management, a “chosen one” hero, and so on? What does it enable that other genres dont’t?

Borrowing from space opera, Mass Effect’s answer was aliens, exploring ethical questions about genocide and AI. On TV, Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica’s starships served as analogues for the extreme isolation and independence faced by tall ships during the Age of Sail, fertile ground for debates on military rule and civilian politics. In literature, The Stars My Destination imagined how personal teleportation would upend society; The Dispossessed and the Mars trilogy played out utopian political experiments on planets where outside interference was believably limited.

What does Starfield do? Nothing. We get grimy Mars, a planet of miners; cyberpunk Neon; high tech Jemison, capital of the generic United Colonies. It is an abject failure of science fiction. There is no saving grace for its terrible navigation, no justification for its dull introduction, no imagination applied to the wonders of interstellar travel.

The most popular casual games are frequently accused (by me) for using the thinnest narrative veneer to stretch quick and easy gameplay into endless, highly monetisable experiences, whether that’s Gardenscapes for match-3 puzzles or Pokémon Go for collecting.

To its credit, Starfield isn’t as aggressively monetised, but its story is, if anything, worse than mid. It’s a testament to the game’s awesomely detailed graphics and bloated universe that even in the absence of narrative drive, it occupies players for as long as it does in its meaningless cycle of combat, collection, and crafting.

But hey: at least the portions are big.

I agree with much of what you said, except for the part about the acting only being "decent". Maybe you didn't go anywhere with Sam Coe, but that's an exceptional performance. And while, yes, a lot of it is exactly as you described, I liked the lore of House Va-Ruun and the UC/Freestar conflict. Basic? Yeah, this isn't sci fi that's going to challenge you overly much. But does it have to? I guess that depends what you wanted from it.